Poetry Review: The Woman on the Other Side – Stephanie Conn

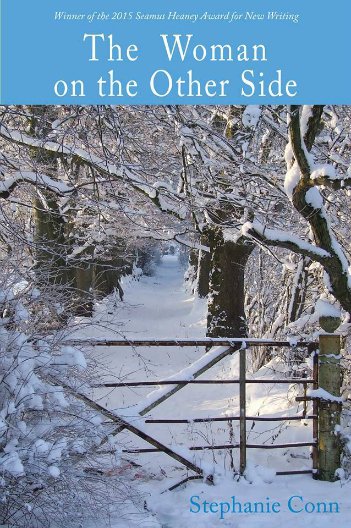

The Woman on the Other Side – Stephanie Conn

The first thing that struck me when I read Stephanie Conn’s debut collection The Woman on the Other Side was the sheer geographical breadth of the subject-matter. It opens with a series of Dutch-inspired poems and then, over its 70-plus pages, ranges effortlessly across Hopper’s Brooklyn, Tsvetaeva’s Russia, a Canadian Christmas, the Atacama Desert and, finally, Tasmania, in a beautiful sequence that mirrors the opening.

While this level of variety is common in debut collections, it is rare that it is structured as robustly and cohesively as this. Conn achievse this in two ways: firstly, by building the collection around implicit sections that are of sufficient length and depth to tie in the reader and secondly, through the cross-stitching of images and themes that echo from one section to another and ground the collection in a common reality. One example of this is ‘Fair Trade’, set in Tasmania, where the poet, recounts the traditions of the ‘Palawa women’ and remarks that ‘Their story isn’t mine to tell and yet I know it by heart. My / daughters carry it with them, and when they gather periwinkles / at low tide on this island beach, they open their hands to the waves’ — an image that harks back to the closing verse of an earlier, darker poem, ‘What We Pass On’.

The element of travelogue provides a spine for the collection, both for the reader and the poet, although in the humour of an early poem, ‘The Ds Have It’, Conn seems to gently remind herself that ‘deltiology is best left / to holidaymakers’. The structure affords the reader ‘a way into’ the collection while providing Conn with a platform on which to integrate a complex lattice of influences and observations, as she sets off on a journey to discover ‘who we are ‘on the other side’ of our experiences and our relationships’.

The element of travelogue provides a spine for the collection, both for the reader and the poet, although in the humour of an early poem, ‘The Ds Have It’, Conn seems to gently remind herself that ‘deltiology is best left / to holidaymakers’. The structure affords the reader ‘a way into’ the collection while providing Conn with a platform on which to integrate a complex lattice of influences and observations, as she sets off on a journey to discover ‘who we are ‘on the other side’ of our experiences and our relationships’.

Opening with the challenge of the title poem (here titled in the Dutch translation Wie is de Vrouw on de Overkant?), Conn quickly moves through the normal travel problems of struggling ‘with the syntax’ and fumbling ‘with a bi-lingual map’. In the second poem, ‘Maria Annastraatje, Leeuwarden’, she is already assertively and succinctly describing her surroundings: ‘The street is narrow, cobbled. / Tall houses rise on either side. / Only a thin rectangle of sky remains.’ This poem also signals some key interests and themes threaded through the collection: flowers as the axis of aesthetics and emotions; the ekphrastic influence of other artists — in this poem represented by Klimt and Vermeer — but perhaps, most significantly, how the ‘I’ in the poem goes ‘to focus / on slate tiles tilting towards the sky’, both reinforcing the theme of exploration and introducing the celestial space as a unifying theme for the myriad of geographies in the collection.

The Dutch sequence segues from a suite of physical poems inspired by the experiential study of geography and sociology, into a triptych of interiors by Vermeer – ‘Reflections’, ‘Vermeer’s Nether Land’ and ‘Painting Light’ – poems that are geometric and measured, all shadows and light, shot through with ‘half-lit rooms draped with silk and shadow’ and ‘whispers of fluid light, / leaving us spellbound by silence.’ They are perfectly matched by ‘View from a Rocking Chair’, inspired by Edward Hopper, and the feeling of bare, cold interiors carries through to ‘the undersea under-piano world’ of childhood, captured first in ‘The Duel’ and echoed starkly both, by the image of being ‘lead-legged on the parquet floor as mother / sneers at the words that flowed from my pen’ in ‘The Metronome’, and by the opening lines of ‘Her Diaries’.

Lines inspired by Marina Tsvetaeva and delivered with masterful echoes of Vermeer.

The early poems in the collection seek to describe a response to the external world, whether physical or aesthetic. In ‘Duel’ and ‘Her Diaries’, and most particularly in ‘Going Dutch’, which closes ‘We split the photos, the phantom booties, / one blue, one pink -/ and never spoke of things again’, Conn starts to look at the more internal world of childhood, family and relationships, and this potent mix of the external and internal is carried seamlessly through the collection. The powerful ‘Blinking in the Dark’ – its muscular form, breathless rhythm and matter-of-fact language – introduces us forcibly to this world, encapsulated in the poignant, yet wonderfully-observed, ‘I hear their laughter from another room’, the note-perfect evocation of a childhood accident in ‘Bangor’, memories of fractured lives in ‘What We Pass On’ and the eternal sadness of ‘The Last Photograph’.

The external world returns in the shape of the barren landscapes of ‘Sulphur Mining’ – ‘these are not scuttling volcano-beetles / scavenging for food, but men / scaling the sides to feed their children and their wives’ – a hardship mirrored in ‘Absolute Desert’, where ‘villagers in Chungungo catch fog in mesh nets / so moisture can condense and trickle into copper troughs’, preparing us in some way for the extremes of ‘Mercury’, where the choice is simple, ‘Fry or freeze.’ In seeking to understand the vicissitudes of life, Conn often looks to the heavens for explication as, in ‘Eclipse’, the quotidian task of choosing flowers is overshadowed by a passing moon, like some dark memory and in the clever word-play of ‘Making Up the Numbers’ each of us is like an anonymous star, ‘though the odd one wanders off course, rising / shattering the equilibrium, going giant with rage.’

The Tasmania-inspired sequence that (almost) closes the collection serves as a microcosm, reprising, as it does, key themes, and, in so doing, has the effect of closer stitching. The first three poems create a footing in the ‘New World’: through found quotes from convict tattoos scratched on their seven month journey, in ‘Pinprick Work’, ‘Till I poor convict greets my liberty’; in the ironic tourist vernacular of ‘Enjoy Your Stay / Port Arthur, 1870’ and the cove-shaped visual poem ‘Absconders Beware’. The ekphrastic is here in the shape of ‘Wurrungwuri’ and in Conn’s response to two Tasmanian poets, Lyn Reeves (‘Fair Trade’ with its echoes of the earlier ‘What We Pass On’) and Louise Oxley (the beautifully sensual ‘Vinification’). Once more Conn is drawn to flora for colour, both aesthetic and emotional, as in a ‘Poppy Crop’, ‘the colour of tears’ and ‘Lavender Fields’, where ‘The lilac moon keeps us alert, that and our finger tips.’ What begins ostensibly as a nature poem, ‘Penguin Watching on Redbill Beach’, finds a parallel layer of connection back to home, similar in theme to the earlier ‘Display’, in the form of teaching ‘six year olds to stick cut-out penguins / on A3 sheets of ice and snow’. As she has done in other sections of the book, Conn temporarily interrupts this idyllic Antipodean world with the heart-breaking vignette, ‘When You Leave’. The collection closes with the fitting ‘Tessellation’, life’s mosaic now firmly in place.

In this collection Stephanie Conn has set out on a journey to find The Woman on the Other Side, her approach perhaps subconsciously hinted at by the title of the fifth poem in the collection, ‘Delta’. All of our lives are comprised of disparate channels, some separate, some contiguous and, in this quest, Conn has pursued each with meticulous attention, always mindful of the inter-dependencies. The result is a wonderfully-crafted, elegant blueprint for a life which, no doubt, offers tremendous satisfaction to the poet and endless invigoration to the reader.

Stephanie Conn’s ‘The Woman on the Other Side’ is published by Doire Press.

Hear Stephanie Conn read from ‘The Woman on the Other Side’ at Staccato Spoken Word Night – Toners, Baggot Street, tonight, 31 August, from 7.45pm.