Literature on Film | Part 1 | Francis Ford Coppola’s Adaptation of Bram Stoker’s Dracula

When I was growing up I was not allowed watch horror films. To a budding film enthusiast their complete absence from my growing viewing inventory only stoked my curiosity to find out what was so special about these movies. On Friday evenings (Fridays were the film night in my household) I would walk with my Dad down to the video store and while he would always try steer me around to the kid friendly movies, I would inevitably end up in the horror section eyeing up the sleeves for films like Leviathan, Fright Night, Critters, Child’s Play, The Amityville Horror etc. Of course none of these ever made it off the shelf and into my hand, and I spent many a Friday evening wondering why my parent’s put considerable effort into making me more familiar with Fievel than with Chucky. This all changed one wet Saturday afternoon when I was about six or seven years old. My dad rented a film for my sister and I called The Last Unicorn (if you are unfamiliar with this film then count your blessings). To say we were traumatised after watching it would be an understatement; my sister and myself still talk about it today. It was the first time I remember a film scaring me silly as The Last Unicorn is a very dark film, full of demons and skeletons and evil kings and absolutely not for children. Of course my father knew none of this when he picked it off a shelf, he just saw a cartoon about unicorns and thought bingo, instant afternoon filler! He probably wondered what all the wet beds were about for a fortnight after. That was my first scary film and I went, in that moment, from having absolutely no experience at watching scary movies to having the bejaysus scared out of me – and I liked it!

So began my fascination with horror films, a passion that was only sated by sneaking downstairs when my parents were asleep to watch the late night horrors on BBC and Channel 4 or organising sleepovers in friend’s houses that were really designed just to watch A Nightmare on Elm Street or It. I remember certain moments from each of these films, moments that stand out and are as vivid to me now as they were then – Freddy making a mess of Johnny Depp’s bed sheets or first hearing Pennywise’s demonic voice for instance – but none have lingered like one certain scene from Bram Stoker’s Dracula. With our parents out for a Saturday night, my older sister and I sat down to watch Francis Ford Coppola’s horror masterpiece. I was 11 and she was 14 years old. The scene I remember so clearly was the ragtag bunch of vampire hunters entering Lucy’s crypt. It. Gave. Me. Chills. It still does. Her cream bridal/death gown, her porcelain white complexion and burning red lips, the dim candle flicker, the glass coffin, the pale moonlight floating in from the open crypt door and the cries of the infant that Lucy intends devouring. Even typing this now I’m getting goose bumps, such is the power of recall – I’m not a man in my thirties but I’m a kid again, clutching a cushion and squeezing it to the point of bursting, almost ready to give my sister the well understood nod that meant turn it off, I can’t take it any more!!! Bram Stoker’s Dracula is not only one of my favourite horror films but was also my proper introduction to the character of Dracula. I was then, as I am still, captivated by Coppola’s gothic masterpiece.

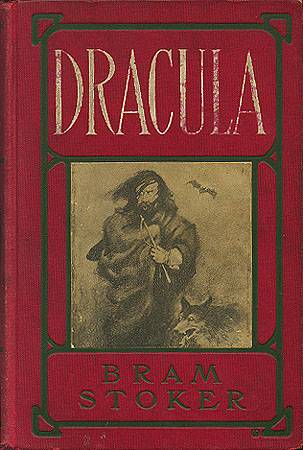

Bram Stoker’s Dracula was released in cinemas in 1992, 95 years after Stoker’s source novel was first published. In those 95 years we had hundreds of stage and screen versions and variations, making Count Dracula second only to Sherlock Holmes as the most widely known fictional character to grace the pages of a novel, a stage or the silver screen. He is synonymous with the vampire character, the archetype when it comes to studying vampires and all their incarnations in popular media. Dozens of actors have taken their shot at playing the eponymous villain, Bela Lugosi and Christopher Lee being the two most closely associated with Dracula, Lee playing him 9 times on screen and is, for many, the definitive Dracula. Yet the fact remains that the general public don’t really know the story of Stoker’s original novel. If you had only ever seen the film versions and never hefted the novel to read then you would be completely in the dark as to what Stoker wrote and what he wrote about. Though there have been over two hundred film version of his tale, no filmmaker has ever really tried to bring the novel, as it was written, to screen.

The Horror of Dracula, Terence Fisher’s 1958 Hammer Horror version and the first to star Christopher Lee, has only one thing in common with Stoker’s novel – the title. The film shares virtually none of the structural or thematic beats that made the novel a horror classic. In many ways it tells a completely different story and I recall my first viewing of it (on the big screen in the IFI some years ago) to be one of confusion and a little disappointment. It took such liberties with Stoker’s novel that it really shouldn’t have carried the title Dracula at all. Yet Horror of Dracula is a master class in horror cinema, a brooding, tense and atmospheric film concerned with the character of Dracula but not Stoker’s story. The same can also be said for Tod Browning’s 1931 version; it bears little or no resemblance to the novel at all, a few names are the same and Count Dracula decides to buy some property in London, after that it severs all ties with the novel. This is in part due to the fact that Browning’s Dracula was not based on the novel directly but on the stage play by Hamillton & Deane, itself a loose adaptation of the novel. From Hamilton & Deane came the black cape, tuxedo and medallion, elements of the Dracula persona that became tied to the character down through the generations.

Francis Ford Coppola’s version cannot claim to address this imbalance in character versus story, as he didn’t faithfully adapt it either. His tinkering with Stoker’s story is minimal, but the changes he makes to the title character are quite radical, which alters not only how we perceive him but also his motivations. Whereas previous filmmakers had kept Dracula as the monster of the piece and built a story to suit him, Coppola kept the structure of the novel almost completely in tact and instead moulds Dracula around it, turning Dracula from a demonic creature of the night to a fallen angel, a romantic hero of sorts. Yet this adjustment to the character was not new to Coppola either; the notion of Dracula being involved in a love story had been teased about in several screen versions prior to his, most notably in Dan Curtis’s 1973 version starring Jack Palance as the titular Count. Here Lucy Westenra is the reincarnation of Count Dracula’s long dead wife, not Mina Murray. Or John Badham’s 1979 version where Lucy, played as the Mina character, falls in love with Dracula and attempts to flee to Transylvania as his vampire bride. I am labouring this for a reason to highlight the fact that filmmakers have played havoc with Stoker’s work and because of this there exists not a single true cinematic adaptation of Dracula, not one. Because of this the millions (possibly billions) of people around the world who are familiar with character of Dracula are, at the same time, totally unfamiliar with Bram Stoker’s novel version of Dracula. This is not necessarily a bad thing as the lack of understanding created by numerous different screen iterations of the novel has created a flexibility that many other literary characters have not been afforded. Filmmakers have distilled the essence of Dracula – the dark, cold-blooded menacing villain – and tied themselves to that instead of Stoker’s text; this may then be the reason why Coppola’s 1992 version is such a different film than previous entries. It gives the most accurate screen portrayal of the novel in its totality, something an audience has never seen before while also re-imagining the key tropes associated with the titular character, something they have also never seen before.

Where previous filmmakers showed a blatant disregard for Stoker’s prose, Coppola embraced it, going as far as gathering the main cast together and reading the novel aloud before principle photography commenced. Coppola insisted on the cast understanding Stoker’s novel from start to finish and instead of diluting Stoker’s work he made a conscious decision to include as much as possible, often to the detriment of characters such as Jonathan Harker and Mina Murray (Harker’s role in the final act is considerably diminished). This may be all the more surprising considering how he took the character of Dracula and virtually discarded Stoker’s most famous creation. Yet at the same time Coppola had little choice; Dracula had become such a familiar character he had descended into the realm of the panto villain. Dracula was at that time little more than a joke, the Lugosi face making and the full body theatrics that had dominated Christopher Lee’s incarnation were now being aped in exploitation films like Blackula, Japula, Rockula and Deafula (a Dracula film told entirely through sign language). While giving the audience back the novel, Coppola took away the character and made it something completely different. Richard Corliss, the then editor of Time magazine, wrote,

“Coppola brings the old spook story alive …To the director, the count is a restless spirit who has been condemned for too many years to interment in cruddy movies. This luscious film restores the creature’s nobility and gives him peace.”

There are three things that set Francis Ford Coppola’s film apart from other screen Draculas – his approach to the visual effects, his attention to costume design and, most importantly, his recalibration of the character of Dracula. To give an idea of what Coppola achieved in terms of the visual effects, it is important to look at where it came from in terms of technology. Bram Stoker’s Dracula was released less than a year after Terminator 2: Judgement Day and also less than a year before Jurassic Park, sandwiched neatly between the two films that heralded the coming of the digital revolution. CGI was rapidly becoming the norm and SFX crews used it almost absolutely. In the early stages of pre-production, Coppola told his SFX team what he wanted and how he wanted to achieve it – namely he wished to use on-set in-camera effects, utilising the full gambit of the then defunct tricks of back projection, double exposure and matte artwork to create his dreamlike, erotic vision of Stoker’s novel. He was told in no uncertain terms that what he wanted was impossible, that is without the use of CGI. Coppola, unbowed, fired the SFX team and hired his son, Roman Coppola, to oversee the practical, in-camera effects. A second unit and visual effects director, Roman Coppola believed he could realise his father’s vision and this decision may be the most important one in terms of appreciating what Coppola achieved with Bram Stoker’s Dracula.

Set in 1897, Coppola wished to use the fledgling cinematic technology of that age to create a film that, if made in the early 1900’s, would not look radically different, in fact there is nothing in this film that postdates the 1920’s. The use of miniatures was one such tool that Coppola employed with distinction. By the early 1990’s miniatures were a dying art form but Coppola embraced miniatures for sequences such as the steam train cutting through the Carpathian Mountains married to the red Transylvanian night sky at the beginning of the film or the rapid, bird-like camera movements around Hillingham Estate as Dracula seeks out Lucy. Yet Coppola was adamant about one thing, he was not using miniatures because they would look better, much to the contrary, he wished to create a deliberately artificial take on Victorian England – he did not aim to create a sense of the real but an artistic impression of it. In doing so Coppola drew heavily upon the art of Edvard Munch, Frantisek Kupka, Jan Toorop, Alfred Kubin, Jean Delville and Gustav Klimt. His film bears the fingerprints of their gothic, disturbed and haunting images throughout (Coppola’s motto during shooting this film was, if you’re going to steal then steal from the best!). For instance, Jan Toorop’s Three Brides almost exclusively influenced the depiction of Dracula’s three vampiric brides in Castle Dracula. Likewise, the work of Gustav Klimt can be seen in many of Dracula’s costumes and the sketches of Alfred Kubin were direct influences on the mountainous Transylvanian countryside and Dracula’s crumbling castle itself. His castle was one of the artistic triumphs in this film, sitting like a rotting corpse upon a throne; Castle Dracula rises high above its surroundings, the crumbling upper reaches hanging like Dracula’s sharp spindly fingers, as if Dracula himself sits upon it and scans the breadth of his desolate domain.

While singling out miniatures, Coppola also used as many tricks of the Victorian age as possible. Many of the exterior shots and night shots are back projected (meaning the foreground action took place in front of a translucent screen where a previously filmed sequence or image was projected on to it from behind). The numerous superimposed sequences, such as Dracula’s eyes across the night sky in Transylvania and London or the rats walking along the rafter upside down in Castle Dracula are the product of double exposures, where one image is filmed first and then the film stock is rolled back in the camera and the second image filmed over it. While these devices do subvert the notion that the viewer is watching something real, they also highlight the beauty of the processes involved. His masterful use of these antiquated visual effects recollect the Universal and Hammer horrors from decades earlier. While Tod Browning and Terence Fisher could only employ these visual tricks, the fact that Coppola chose to use them can be seen as a tribute to these films. In fact he visually references Lugosi and Lee’s take on Dracula during Harker and Dracula’s first meeting in Transylvania. Turning away from Harker, the Count’s shadow draws its flowing gown around itself, covering Harker in shadow like the Draculas of old did when about to feast on a buxom maiden. Or Dracula’s evil shadow reaching out for Lucy before he prepares to strike for the last time, his long, sharp fingers needling through the air is strongly reminiscent of FW Murnau’s Count Orlock as he reaches for the sleeping Ellen in Nosferatu.

As mentioned previously, Coppola wished to create an artistic impression of Stoker’s novel and he exhausts virtually every avenue possible to make Bram Stoker’s Dracula a delight to look at, from the iris wipes between scenes to the use of a Pathe hand cranked camera (from the 1890’s). Using shadow puppets and silhouettes he creates the nightmarish horror of Draculea’s battle sequence, which opens the film. It was a bold choice, to remove what would have been an action set piece and replace it instead with a low lit and blatantly artificial sequence. Showing Draculea at his most gruesome and bloodthirsty, this fantastically creative section does so without displaying one drop of blood. This in turn only emphasises the shock at the shear volume of blood Draculea spills when defiling the church after the death of his beloved Elisabeta. Showing him victorious in battle and then raging against God only draws sympathy for Draculea and sets him up to be, as Coppola intended, our tragic hero and not the embodiment of pure evil.

Coppola’s attention to detail when making this film is also reflected in the sumptuous costume design. Believing the costumes to be as important, if not more so, than the sets, he intended the costumes to be a means of expressing character. Designed by Eiko Ishioka’s (winning an Oscar for her efforts) and though not a costume designer specifically (Eiko Ishioka started life in advertising and graphic design before she segued into film late on in her career), her film work earned her great acclaim for her visual ingenuity. Bram Stoker’s Dracula was only her third feature film, coming to the attention of Coppola after previously working with him on the poster for Apocalypse Now in 1979. Her costumes, such as Draculea’s muscle and sinew body armour or Count Dracula’s crimson kimono-esque robe or Lucy Westenra’s bridal gown/death shroud, are a perfect mix of period exactness and garish nightmare. Overly stylised and embellished, what they lack in practicality they make up for in shear beauty, indeed Coppola had to shoot some scenes in a certain way to accommodate the costumes and their movement, or lack of, Lucy’s crypt being one of them.

Drawing influences from regions and cultures such as the Byzantine, Asia Minor and the Orient, Ishioka reduced the plot to its very essence, a battle of good versus evil and decided that her costumes should reflect an East versus West cultural divide. This is evidenced in Dracula’s attire; in his weakened state at the beginning of the film he wears a long crimson Kimono, or the white and gold gown he is wrapped in as his gypsy henchmen race him back to Castle Dracula during the film’s climax – both are heavily influenced by Japanese designs and culture. Japan, only emerging from its self-imposed isolation in the late 19th century was, at that time, a vast and unknown quantity. Its culture, artwork, clothes and customs were radically different to Victorian England and how better to convey the mystery and fear of the unknown, the un-dead Count Dracula, than to identify Dracula with those very fears. In his most unsettling guises, as the old man or the half formed monster, he is dressed in kimonos and gowns not unlike those from Japanese culture, yet in garish colours quite unlike those that would have been deemed popular or appropriate in Victorian England.

As proof of the enduring character of Count Dracula, Eiko Ishioka had never seen a Dracula film before starting work on this film yet was familiar with all the assumed Dracula motifs – the slicked black hair, the cape and high collar, the medallion on a red lanyard around his neck etc. She consciously worked against the accepted norms of the character to create a version of Dracula that had never been seen before. Previous portrayals of Dracula never experimented with colour, from 1931 onwards the Count was always dressed in dark, drab, shapeless tuxedos wrapped in an ankle length cape, something consistently and constantly reinforced by subsequent Dracula productions. Dracula had almost become a pastiche of audience expectations. Ishioka, when asked about her take on Stoker’s titular character, she explained;

“During one of our initial discussions, Coppola told me, ‘Dracula is a profoundly mysterious presence, and I want his different sides – human, animal, male, female, old, young, Western, Eastern.”

Paying particular attention to the artwork of Gustav Klimt, Ishioka gave her Dracula “a million faces” as she saw the character going through “endless transformations,” moving from a vigorous Romanian Prince to a frail old man, from decrepit sinister monster to youthful and charming gentleman, each costume reflecting the iteration of Dracula at that moment. Where Christopher Lee’s Dracula never changed costume once, Gary Oldman’s Dracula is dressed in the finest of robes and tailored suits and because of Eiko Ishioka, Gary Oldman is the most elegant Dracula to ever grace the silver screen.

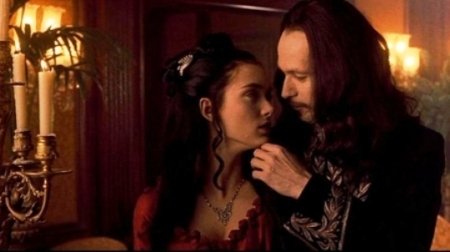

Though widely accepted as one of the most accurate screen versions, much has been made of Coppola’s film bearing Bram Stoker’s name in the title, as this most certainly is not Bram Stoker’s novel. While the film carries all of the novel’s locations, dramatic beats and main characters, most of which have never been included before (Jack Seward, Arthur Holmwood and Quincey Morris namely), it is fundamentally a different tale as told by Stoker. In the source novel and in all film versions up until the 1970’s, Dracula was a monstrous, motiveless killer, driven only by a lust for blood and immortality. He derived a kind of sexual gratification from corrupting human beings and drinking their blood. Coppola was fully sure that audiences were tired of that one-dimensional take on Dracula – he wished to tell a different story. He saw Dracula not as a monster but as a romantic hero, a misunderstood character. Bloodlust was not enough of a motivator for Coppola and his screenwriter James V. Hart; Dracula needed some other reason to intertwine his cursed existence with the lives of Mina Murray and Jonathan Harker. Taking inspiration from the historical character of Vlad Tepes, or Vlad the Impaler, Coppola felt it imperative that Dracula be developed outwardly and wanted to give the audience someone to sympathise with but also be repulsed by. The addition of Draculea, the Romanian Prince who renounces God and defiles a church after the death of his beloved Elisabeta, explains Dracula’s origin. He falls from the light and Oldman played him as a fallen angel cast out from Heaven, something that is pitch perfect in terms of the rest of the film. There are no heroes here and there are no villains, only those that have gone too far in one direction or another.

Though the character of Dracula had always been an overly and overtly sexualised one (his ability to seduce and control both men and women is included in both the novel and countless films), he has never been a character capable of love. As written by Stoker and portrayed in almost all screen versions, Dracula is an evil creature, viewing humans as merely prey and playthings. Oldman eschews this, making his Dracula more of a twisted character forged from the remnants of a broken heart – Vlad Draculea chooses the ways of darkness to gain his revenge on God, becoming Dracula the beast and renouncing Draculea the man. In his Transylvanian castle he lives like a decrepit old hermit, his slow gait, ice pale skin and long bony fingers making him look every minute of his 400 plus years. He does not revel in his immortality and unlike other screen vampires, Dracula does not stay eternally young; instead he flits between youth and old age, as his strength allows him. This, on its own, elevates Oldman’s portrayal above his predecessors as his Dracula is to be both feared and pitied. Integral to this was the romance between Mina and Prince Vlad – if Dracula was to come to England in pursuit of love, and not simply blood, then wouldn’t that transform the character almost totally? Yes it would, and yes it did, as this was not the character that Stoker wrote. While he may have called it Bram Stoker’s Dracula, this film most definitely is not the Dracula that Bram Stoker wrote. Yet, as mentioned earlier, and conversely, no film has brought Stoker’s novel to screen as accurately as Coppola, no other filmmaker has gone to such lengths to bring the novel so vividly to life.

While highlighting the changes Coppola brought to the character of Dracula, it should be noted that this film succeeds mainly on the back of Gary Oldman and his portrayal of the Count. At the time Alan Jones, writing for the Radio Times said;

“…as the tired count who has overdosed on immortality, Gary Oldman’s towering performance holds centre stage and burns itself into the memory.”

This is not an understatement, Oldman, who in the early 1990’s was still a relatively unknown actor, gives the greatest Dracula performance committed to film, mixing evil and charm and camp instead of rehashing what audiences had come to expect of Dracula. Oldman’s Dracula is multi-faceted and layered. He is a hero and a villain, the embodiment of pure evil while also being a foot soldier of Christ. He loves and hates, he creates fear and is fearful himself. In Oldman we have a Dracula that we find repulsive yet attractive, he is pitiless but we are also compelled to feel great pity for him and this is evidenced by his desire to love, maybe the only human trait he has left. His belief that God has wronged him also plays on our sympathies for Dracula as we understand why he turned away from the Church and vowed to avenge Elisabeta’s death armed with the only power he had left, that of darkness.

During the film Dracula references God on numerous occasions, explaining to Harker, with a wry smile, that the relationship his ancestor (Dracula himself) had with the Church had “not been entirely successful.” Also, when confronted by the vampire hunting fellowship as Dracula seduces Mina, he turns into his grotesque bat-man form and teases Van Helsing about holding a crucifix to try and ward him off, “You think you can destroy me with your idols? I who served the cross, who commanded nations…I was betrayed. Look what your God has done to me,” he growls, displaying the full breath of his wickedness, turning himself into a wriggling mass of rats. From this we deduce that Dracula sees himself as the wronged one, he is the victim and this is unique to Oldman’s portrayal of Dracula. It humanises him and removes him from the movie monster pack as, unlike any other screen Dracula, Oldman’s finds salvation in the final act. Lying bloodied and beaten on the steps of the church he defiled 400 years before, Dracula raises his eyes to the cross and asks, like Christ during his crucifixion, “Where is my God? He has forsaken me.” He begins to change; a heavenly light finds his face and his features transform from that of the unholy beast to Draculae the brave Knight and ending as Prince Vlad, the gentleman. He is pure again and for the first time in the entire film we see Dracula is afraid, but also penitent. He has been forgiven and this, his redemption, is the emotional punch the film needed as, being a love story, he was never going to live in eternal darkness with the corrupted body and lost soul of Mina. Simply vanquishing Dracula would not have been an appropriate ending as Dracula was not purely a villain in this film. His entry into Heaven and reunion with Elisabeta takes his character full circle, from religious zealot to diabolical demon to contrite believer. It also makes Dracula’s story complete – there could be no sequels, Dracula is staked through the heart and decapitated. His death is final and Mina’s return from vampire to human shows that the power of Dracula is no more in the world. As endings go it is one of the most satisfying in terms of character arcs.

While the casting department need to take a hearty clap on the back for Oldman, there are a few casting mis-steps along the way and unfortunately Keanu Reeves is one of them. Though much has been made of his British accent and surfer dude delivery, Reeves is not a terrible Jonathan Harker, he is just unfortunate enough to share the screen with two masters of their craft – Oldman and Anthony Hopkins. Daniel Day-Lewis had been considered for both Dracula and Harker but decided to make The Last of the Mohicans instead – can you imagine the magic that could have been if Day-Lewis had taken his chance to square off against Gary Oldman? Winona Ryder, as Mina, also seems on rocky ground throughout the film. She is not wholly convincing, her accent slips at points, yet she triumphs in places too, namely the final seduction where she joins Dracula. She is a perfect counter balance to Lucy’s overt sexual avarice, and her best moments are spent in the company of Sadie Frost’s Lucy.

The supporting cast, on the whole, are very strong – Richard E. Grant seems perfectly cast as Dr. Jack Seward and Bill Campbell, famous to many for being the Rocketeer, plays the Texan gent Quincy Morris to perfection. Even now, after 20 viewings or more, when Quincey meets his heroic demise at the hands of one of Dracula’s henchmen, I still hope against hope that one of the vampire hunting fellowship find a way of saving him. Of all the characters in the film and novel, Quincey was always my favourite. Cary Elwes, who will forever be Westley from The Princess Bride, makes Lord Arthur Holmwood his own. Through the novel Holmwood gets stronger, becoming a more dependable character and Elwes plays this pitch perfectly. He is the affable lord in the beginning, questioning everything, yet, when tasked with staking his own bride, does not shirk the responsibility. It is he who organises the trek to Transylvania as they chase Dracula back to his lair and he who drives them on to vanquish Dracula on the steps of the castle gates, stopped only by Harker when the Count is beaten and retreating with Mina to his chapel. His nuanced performance can be exemplified in one scene. Returning to Hillingham estate with Quincey, Lord Holmwood is shown in to his sleeping bride-to-be Lucy. She is in the final stages of transitioning from human to vampire. In a single, slow, track forward shot, Elwes conveys all the horror and distress at seeing his fiance’s deterioration in an unbroken stare, his expression slowly crumbling as he realises that she is in grave danger. As good as Oldman is in this film, Elwes is his match, if in that one scene alone.

With Anthony Hopkins’ bonkers turn as Abraham Van Helsing we have a character that is very hard to pigeon-hole, as he is not a hero, but neither is he a villain. Channelling some of the chill that made his Hannibal Lector so memorable, Van Helsing is the perfect foil to both Reeves’ obsessed Harker and Oldman’s vengeful Dracula. One of Coppola’s master-strokes was to leave Van Helsing just a little bit ambiguous, he is the only character who you are unsure of when watching the film. It might not be caught on first viewing but Van Helsing may not be all he seems. There are many questions about Van Helsing that Coppola asks but does not answer, the first of which is, how does he know Dracula so intimately? Though the owner of an ancient textbook on vampires, Van Helsing is able to describe to Mina what Draculae was like before the forces of darkness corrupted him. How would he know this? You see, Hopkins plays the priest at the start of the film, the one that will not allow Elisabeta’s body a Christian burial. Is Van Helsing this very same priest? Has he found a way to transcend the forces of time and ageing to chase his mortal enemy? If you look at Van Helsing’s first meeting with Mina, he dances with her with a strange energy, telling her that she is “one of the lights” in the world. As they part he smells her skin, just a brief sniff, but from this he knows that she has been in contact with Dracula. If he is something other than human, a Church sanctioned bounty hunter, does Van Helsing have the vampiric heightened sense of smell and sight and hearing? Also, after Lucy’s first blood transfusion, Van Helsing is able to move with an inhuman agility and speed. How does he cross the garden in the blink of an eye? Or could Van Helsing just be an ancestor of the priest, has his family taken the mantel of vampire hunter down through the generations? As Quincey lies dying in the final scene’s Van Helsing laments, “We have all become God’s madmen”, is he referring to the other members of the fellowship joining him as one of God’s madmen? Does he fully accept that he has descended into a strange place when only violence and destruction can achieve the intentions of God? What ever the answer, beyond doubt is the power of Hopkins’ wild-eyed and eccentric take on Abraham Van Helsing. While Oldman gives us the best portrayal of Dracula, Hopkins delivers the best version of Van Helsing also.

Bram Stoker’s Dracula is comprised of many things; it is a horror, a romance, a revenge film and a melodrama but above all else it should be read as a love letter to cinema. Coppola, one of the greatest living American directors, crafted Bram Stoker’s Dracula with a love that he has not been able to equal since, and displayed an energy he had not been able to capture since 1979’s Apocalypse Now. There is something undeniably special about Bram Stoker’s Dracula and while the title is misleading, Francis Ford Coppola took the source material and used it as a template to tell his Dracula story, not the Dracula story. Prior to this, all previous films found themselves, either by default or by design, slavishly tied to the accepted norms of the Dracula character. It should be noted that the official sequel, Dracula Un-Dead by Dacre Stoker and Ian Holt uses Coppola’s film as its origin and not the book, so many of the changes that Coppola made to the character and story are kept, itself a testament to what Coppola achieved in making Dracula new and relevant. Unlike previous versions, this lavishly overblown film is an opulent and operatic take on Stoker’s novel, one that returns the character of Dracula to the nobility of whence it came. Being a decadent examination into the latent sexuality of the Victorian era, and the man himself, the film gives the character, but also the story, room to breathe and to evolve into something more than a horror film, something a little more beautiful.