Lady Mary Wortley Montagu, Poet and Medical Pioneer

Mary Wortley Montagu was born as Mary Pierrepoint in 1689. Her father Evelyn was the Earl of Kingston, and Mary was his eldest child. Her mother (also named Mary) died when she was only three years old, and Mary was handed into the care of her father’s mother, Elizabeth. [1] When Elizabeth died in 1698 Mary and her siblings (a sister named Francis and a brother named William) were returned to their father’s household. It was an unusual upbringing – the Earl was a major political dealmaker in the court of William III (and Queen Anne, from 1702). He regarded his children as props in his political career – one incident in Mary’s childhood, when she was eight years old and still in her grandmother’s care, serves to illustrate this. It was a tradition for the members of the Earl’s club (the Kit-Cat Club) to choose a notable beauty of the time to drink a toast to. On one occasion the Earl declared that his daughter Mary should be the toast, as she was more beautiful than any of the ladies who they had nominated. The gentlemen of the club protested that they could not toast a girl they had never seen, and so Evelyn sent for her and had her woken from her sleep and taken in a carriage to the club. There the members of the club, entering into the spirit of the affair, declared her indeed the greatest beauty, toasted her health and gave her sweetmeats. It was a strange and dreamlike episode which had a profound impact on young Mary, and one she recalled fondly throughout her life.

As the Earl’s eldest daughter, it was Mary’s duty to serve as hostess for his social events once she reached her teens. She was rigorously trained for this, and three times a week had to study carving meat from a master in the trade in order to ensure she could meet her social obligations. But her fierce intelligence was hardly satisfied by this type of learning. Instead she began, in her own words, to steal an education – “trespassing” in Latin and Greek, and studying works both classical and modern. Like many such students she began by translating classical works, the most notable of which was her translation of the Enchiridion of Epictetus, a work of Stoic philosophy considered a classic manual of advice for life. She sent this translation to Bishop Gilbert Burnet, an ally of her father’s, in 1710. Burnet was a well-respected scholar and historian as well as a politician and cleric, and he was impressed both by Mary’s translation and by the letter she sent accompanying it presenting a case for woman to be allowed a formal education. Whether this brought the bishop to her side or if it was he who had suggested the Enchiridion to her in the first place is unclear, however later in life she acknowledged a debt to him for having directed her studies. She had an excellent memory and read voraciously, building a foundation of knowledge for her own writing that stood up throughout her life.

Mary was initially opposed to marriage, and resisted attempts to marry her off young. In fact she seems to have considered some form of cloistered life as a nun, though she changed her mind when she met Edward Mortley Montagu. He was the cousin of a friend of hers, and the two began a correspondence that developed into romance. Edward visited her father and sought her hand in marriage, and reportedly initially things went well. However the discussion soon broke down over the matter of entailment of property, with Edward philosophically opposed to legally binding his property and lands in the aristocratic style to be inherited by his children without regard to his will. The debate turned acrimonious, and the Earl rejected Edward as a suitor. He and Mary kept up their correspondence in secret, and in 1712 she told him that her father had ordered her to accept the marriage proposal of an Ulster noble named Clotworthy Skeffington. [2] Mary had no desire to marry Clotworthy, who she detested, but her father told her that if she refused he would have her kept in a remote country house during his life, and cut off after his death with a pittance. With no other option she could accept, Mary and Edward eloped and were married in August of 1712. Her father was furious.

As a result of the scandal the pair at first lived out in the country in relative obscurity. Mary took the chance to begin growing her list of literary contacts. Joseph Addison was a friend of her husbands who visited them, and Mary not only read the manuscript for his new play but gave him some constructive criticism which he used to help him improve it. The play was Cato, a tragedy – a play which would come to be considered a classic. Addison was a good friend to make. He was extremely well connected in London’s literary scene, and would go on to found the Spectator magazine in a few years. Meanwhile Edward and Mary Wortley Montagu soon discovered they were an ill-matched pair, though Mary did her duty and presented her husband with a son in 1713. He was named Edward after his father, though he would prove to be more his mother’s son. The same year brought tragedy into Mary’s life, however. Her brother William contracted smallpox and died, only a few months after Mary had her son. At the time the disease was endemic, killing 400,000 Europeans a year, and few were left untouched by it directly or indirectly. This came as an even greater shock to Mary because she had no idea that he was ill, as her father had kept her from much contact with the rest of her family.

The couple’s exile came to an end in 1714, when Edward was made a junior Lord Commissioner of the Treasury. He was able to set up a household in London, and Mary finally achieved her dream of living in the capital. She soon became a part of the literary “set”, and her first published work was a poem in the Spectator under the pseudonym of “Lady President”. She became friends with the poets Alexander Pope and John Gay, and the three collaborated on writing three short satirical playlets that would become infamous as the Court Eclogues. In 1715 Lady Mary caught smallpox, and though she survived it she was left scarred – she lost her eyebrows entirely, and her famous beauty was gone. In a poem published in 1716 called Saturday; The Small-Pox she wrote:

Ye, cruel Chymists, what with-held your aid !

Could no pomatums save a trembling maid ?

How false and trifling is that art you boast ;

No art can give me back my beauty lost.

Despite the poem, she seems to have been mostly grateful to have survived the illness. She was far more distressed by the social shame she suffered in 1716. The Court Eclogues had never been intended for general publication, but had been privately printed for distribution among a small group of friends. One of those friends left a copy in Westminster, where it was found by a stranger. Pope and Gay were famous writers, and an unpublished book of poems by them was worth a great deal of money, and so a pirated copy was printed and made available to the public. Unfortunately for Mary, one of the eclogues was seen as an attack on Princess Caroline (wife of the heir to the throne). Caroline had thought of Mary as a friend, and though the poem was not meant meanly it still led to a great deal of ill will. It may be because of this that Mary would be averse to having her work published for the rest of her life. It may also be why her husband was offered the post of Ambassador to the Ottoman Empire. He accepted, and Mary and their son travelled with him away from the scandal, to Europe.

It was during these two years of travels that Mary produced what was to eventually be her most famous work – Letters of the Right Honourable Lady M—y W—y M—e, more commonly known as Letters from Turkey. These consisted of both genuine letters she had written (to people such as her sister and to Alexander Pope) and letters to imaginary people she wrote to serve as descriptions of her voyage, though these imaginary people develop a character of their own in her writing. Mary had never before left England, and even Europe seemed strange and exotic to her. Her account of the feuds that divided the women of a German town into a dozen warring factions is an example of something a male traveller would never have even seen or written about, and illustrate her unique vantage point. Devastatingly on point is her assessment of the ladies of Vienna, who she described as free of “the two sects that divide our whole nation of petticoats”.

Here are neither coquettes nor prudes. No woman dares appear coquette enough to encourage two lovers at a time. And I have not seen any such prudes as to pretend fidelity to their husbands.

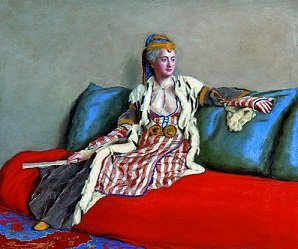

The Montagus, of course, were a fairly standard aristocratic couple of the period. Which is to say that he was unfaithful from the beginning while she had the discretion to wait until she had given him children before beginning her own affairs. At this stage their only child was young Edward, and so she declined to take part in the Austrian sport – much, she said, to the bafflement of the nobles. Edward and Mary spent several months travelling around Austria and the German kingdoms before finally setting off south through Hungary in January 1717. On April 1 Mary wrote a letter to Princess Caroline, telling her that she had arrived in Adrianople on the Turkish border. She spoke of the warm climate, but quickly added that the country could hardly be preferable to England where Caroline’s father in law George I “makes his own happiness consist in the liberty of his people”. It was in Adrianople that Mary had her first experience of a Turkish bath, which she described as “the lady’s coffee house” – though without “those disdainful smiles, and satirical whispers…when any body appears that is not dressed exactly in the fashion” – for the simple reason that everybody was naked. Naturally in her letter Mary insists that she did not join in this custom, claiming to have dissuaded them from having her strip and join them by showing them her complicated Georgian undergarments, which they took for some kind of chastity belt. Of course Mary also commented on the ease with which the concealing dress the woman wore in public allowed them to carry on discreet affairs in anonymity. Later in her trip one particular discovery that delighted her was the secret codes embedded in the gifts passed in innocuous gifts between lovers, where a pear appealed for hope while a clove symbolised love previously undeclared. Mary spent several months in Adrianople, being entertained by the local noblewomen, until she and Edward moved on to Constantinople in May.

Here from my window I at once survey

The crowded city, and resounding Sea

In distant views see Asian mountains rise

And lose their snowy summits in the skies.

…

The rising city in confusion fair;

Magnificently formed irregular

Where woods and palaces at once surprise

Gardens on gardens, domes on domes arise

And endless beauties tire the wandering eyes,

So sooths my wishes, or so charms my mind,

As this retreat, secure from human kind.

Constantinople

Istanbul (or as the British insisted on calling it, Constantinople) was an ideal refuge for Mary – a world away from the world. Her letter home ceased for a while after her arrival, partially due to the distraction of being in such a new and engrossing place, and partially due to another distraction. Mary was pregnant again, and gave birth to a daughter (also named Mary) on the 19th of January 1718. It was after her daughter’s birth that the ladies of Istanbul introduced her to their custom for the prevention of smallpox – that of “engrafting”, where a young person was deliberately infected with a minor form of the disease in order to give them the immunity that prevented reinfection. Mary, having lost a brother to the dread disease, was convinced enough by their testimony to have her son successfully inoculated in this way. She went on to become a lifelong proponent of the practice. Though the trip was good for Mary it was less so for Edward, who failed in his diplomatic goal of brokering a treaty between Austria and Turkey. After a year in the city they left Istanbul in June, with Mary writing the month before of how she walked the city to see all that she could before she departed. Their journey home took them east, through Tunisia and the ruins of Carthage, before they crossed the Mediterranean to Italy and so through France home once more. On the 2nd October 1718, over two years after the had departed, Edward and Mary Wortley Montagu returned to London once more.

Mary soon resumed her friendship with Princess Caroline and reestablished herself in the literary circles she favoured. Her wit and charm made her a popular and esteemed member of society. The couple bought a house in Twickenham, where they would live for the next twenty years. By this stage their marriage had cooled into relative indifference, and Mary conducted more than a few discreet affairs over the years. One of these was with Philip Wharton, Duke of Wharton. He was nine years younger than her, but as her later affairs would show Mary’s taste seems to have run to younger men. Philip was notorious, and among his other exploits founded the first Hellfire Club. Mary is said to have gone along to several meetings as his guest. After her affair with Philip cooled (his political eccentricities making him more and more dangerous to know) her old friend Alexander Pope may have tried his luck. It is certain that some time in the 1720s their friendship, once close, came to a bitter and acrimonious end. Less certain is why, though legend and later artists have it that Alexander proclaimed his love to Lady Mary, and she responded by breaking into incredulous laughter. This may explain why he later referred to her as “Sappho” in the satires he wrote – the implication of promiscuity (and lesbianism) was clear. Mary was willing to give as good as she got however, and directly responded to one of his attacks with a poem that declared:

Satire should, like a polished Razor keen,

Wound with a Touch, that’s scarcely felt or seen,

Thine is an Oyster-Knife, that hacks and hews;

The Rage, but not the Talent, to Abuse;

And is in Hate, what Love is in the Stews.

Despite her feud with Pope, Mary’s literary reputation continued to grow. She edited her Letters from Turkey for publication, but in the end decided to forgo the publicity they would produce. Instead she left them with a lawyer in Paris, with orders that they be published after her death. [4] She was good friends with John Hervey, a noble of the court who became famous the following century when his viciously frank memoirs of court life, written secretly during his life, were published. At the time he was best known for the attacks Alexander Pope levelled at him for the crime of being Mary’s friend, usually crude and homophobic attacks that targeted Hervey’s bisexuality. Whether he was (as Pope suspected) Mary’s lover is unknown. Another productive feud Mary engaged in was with Jonathan Swift, though this was more down to a severe dislike for his work and its content than any personal conflict. (And also possibly a political disagreement – Mary was a die-hard Whig.) One work of his that she really hated was The Lady’s Dressing Room, where a man sneaks into his lover’s room and is horrified to find used handkerchiefs, stained towels and worst of all a used chamber pot. Mary accused Swift’s hero of trying to excuse his own impotence by blaming his paramour, and implied that his verses had been written in fulfilment of a threat of revenge on a prostitute who had refused to return his money. Her poem ended:

She answered short, I’m glad you’ll write,

You’ll furnish paper when I shite.

Mary did write more serious works however. One of the most influential was a series of articles describing, promoting and defending the practice of inoculation against smallpox that she had seen in Istanbul. When an epidemic swept the country in 1721 she had her daughter inoculated, and she persuaded Princess Caroline to have her two daughters inoculated. Most English doctors regarded the process as barbaric folk medicine, however the doctor who had carried out Edward’s inoculation in Istanbul had since returned to England and was persuaded to carry out the procedure. He also demonstrated it on six condemned prisoners from Newgate, who had their death sentences pardoned in exchange for allowing the procedure (which they all survived). Though inoculation against smallpox would be superseded by vaccination with cowpox before the end of the century, Mary’s advocacy did a great deal to lay the ground on which vaccination was able to succeed – not to mention the many people who survived in England and its colonies in the following decades due to the practice she introduced.

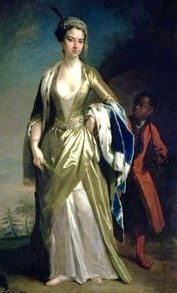

Mary’s work is notable for its feminist overtones, visible in works such as On The Death Of Mrs Bowes where she bitterly congratulates a woman known to have been abused by her husband on having escaped her marriage through death; and in Epistle from Mrs Yonge to Her Husband which derided the double standard that saw divorced women ostracized from society while divorced men suffered no consequence. Her writing was also frank and sex-positive in tone, as evidenced by her discussion in her Turkish letters or in poems such as A Receipt to Cure the Vapors, where she advises a young woman who is grieving for her dead husband to take a lover to console herself. She also wrote about the treatment of her sister Frances, who suffered from mental illness and who Mary had herself appointed guardian for in 1731. Mary’s public life matched her writings – she was infamous for refusing to wear the elaborate wigs that were the fashion at the time, and instead preferred to wear the Turkish-style clothing she had become fond of in Istanbul. On one occasion she was reportedly told at the opera that her hands were dirty, and replied “You should see my feet.” Her habit of taking snuff was considered equally unfashionable and unbecoming of a lady, but Mary had more than enough social credit for people to class this as a harmless eccentricity.

Her son Edward seems to have inherited his mother’s disregard for social conventions. After the family returned from Istanbul the five year old Edward was enrolled as a pupil at Westminster School, but ran away for the first time within six months. He was missing for a year before his governor by chance found him selling fish at a dock in London, having spent a year working as a fisherman’s apprentice. He ran away again in 1726, and was caught in Oxford. The follow year he once again escaped the school and this time he made it as far as Gibraltar before he was caught. This seems to have made his father accept that wanderlust was part of his son’s nature and so he sent him off to Italy in the company of a tutor. This served to keep his attention, though when he returned to England in 1732 he further scandalised his parents by marrying a laundry lady who was several years his senior, apparently on a complete whim. The woman was paid off and young Edward was forcibly deported to the Netherlands out of sight and mind. He would go on to serve in the British Army and spend a year as a prisoner of war. After that he was elected to be an MP for several years. He was incarcerated in France for the unforgivable crime of cheating at cards, then returned to England and became a Fellow of the Royal Society. He bigamously married an Irish Catholic woman (his previous wife had died, her previous husband had not – though Edward managed to convince her he had), fathered multiple illegitimate children (some mixed-race) and generally proved an utter embarrassment to his family.

Edward was not the only one of Mary’s children to vex her. In 1736 her daughter Mary (a much more sensible child than Edward) married John Stuart, a Scottish Earl. Neither of her parents approved of the marriage, as John seemed to be a somewhat ineffectual man mostly interested in botany. [5] It was also in 1736 that Mary first met Francesco Algarotti, an Italian nobleman. Francesco was a writer and student of the sciences who was regarded as one of the most intelligent men in the world at the time. Though Mary was over twice his age (she was 47, he was 23) the two had an affair. Her main rival for his affections was her own ex, John Hervey – though some suggest that this was less a rivalry and more mutual arrangement. Francesco soon returned to Italy but he and Mary kept up their correspondence. In 1739 she left England claiming that she was travelling to the south of France to spend the winter in the warmth. However her real destination was Venice, where she was supposed to be meeting Francesco. Though he never turned up (he had been summoned to Berlin by Frederick II, King of Prussia) she decided that she didn’t particularly want to go home to London. So she didn’t.

Mary spent the next few years travelling around Europe, before settling in Avignon in France in 1742. She did meet up with Francesco in 1741 but it failed to recreate whatever magical experience it was in 1736 that had inspired her to leave home. In 1746 she left Avignon According to her own account (which was apparently dictated as evidence for a possible court case) this was at the invitation of a Count Ugolino Palazzi, a friend of friends, to visit his family home in Brescia, northern Italy. (It is generally accepted that the Count was her lover, though Mary herself of course never states this.) However in order to do so he required a loan to pay off his debts so that he could travel – though he assured her that his mother would repay her. However the Countess turned out to have already refused to pay these debts for her son (something Mary had also done when presented with her own son’s debts), and so Mary decided to write off the loan. Mary planned to travel on to Venice but suffered an illness that left her bedbound. It was the beginning of an intermittent series of illnesses that left her unable to travel for the next ten years. Some speculate that Ugolino was behind this, and that he may even have poisoned her in order to keep her (and her income) in his power. It is definitely true that when she finally determined to move on in 1756 he did all in his power to prevent it. In the end it turned out that the house she had lived in for most of the last ten years, which he had sold to her and which she had spend a great deal of money on improving, had never legally been available for him to sell as it was entailed as part of his estate. Moreover he attempted to seize all of her jewellery and property as recompense for “unpaid rent”. In total he swindled her out of several thousand pounds, and to add insult to injury claimed to Italian society that the true state of affairs was that the money had been in recompense for his skills as a lover – a slander still repeated by many biographies.

Having finally made it back to Venice, Mary fell into a comfortable routine of travelling back and forth between it and Padua – Venice for when she was feeling social, and Padua for when she found the city’s hectic social life too much and wanted to get some peace and quiet. Conscious of her own increasing age (she was in her sixties, and refused to have a mirror in the house) she enjoyed the Venetian custom of going masked to operas and balls. She had long since reconciled with her daughter Mary and corresponded with her warmly, though her son she had long ago written off as a hopeless case. In 1761 news reached that her husband had died. His will left almost his entire sizable fortune to their daughter, with only a £100 settlement going to Edward. Edward, naturally, challenged the will and a bitter court battle ensued. Mary decided to return home to England to support her daughter, and to visit her grandchildren. She stopped off in Rotterdam where she gave the manuscript of her Letters from Turkey to a local priest she knew, asking him to have them published after her death. In January 1762 she returned to England for the first time in over a decade. She met her daughter and her grandchildren, most of whom she had never seen. By this time the son-in-law she had looked sideways at was now Prime Minister of Great Britain. [6] To some she was a fondly-remembered writer, to others she was a figure who had been involved in satirical wars of words and scandalous affairs, and to yet more she was a hero for introducing inoculation to the Empire and providing some safeguard against the deadly smallpox. To many she was most significant for her daughter, who was the undisputed pre-eminent woman in Georgian society at the time. Regardless of the cause, she was a bona fide celebrity – something she hated. She soon began planning a return to Venice, but fell gravely ill with what turned out to be breast cancer. It soon became clear that the illness would be fatal, something Mary calmly accepted. She drew up her will – leaving all her possessions to her daughter, save for a few bequests to her friends and servants and to her son the calculatingly insulting sum of a single guinea. On the 21st August 1762, surrounded by her loved ones, Mary Wortley Montagu passed away. Her final words were:

It has all been most interesting.

On the 7th May 1763, London publishers Becket & de Hondt released Letters of the Right Honourable Lady M–y W–y M–e Written during Her Travels in Europe, Asia and Africa to Persons of Distinction, Men of Letters, &c. in Different Parts of Europe. The book was an instant smash success. Mary’s reluctance to see her work published during her lifetime, and her fondness for pseudonyms when she was published, had left few aware of her skill as a writer. The initial copies sold based on her fame and her relationship to the recently deposed Prime Minister, but once people realised just how good the book was it began to fly off the shelves. The book was revolutionary in several aspects, not least for showing that women were capable of offering an entirely different viewpoint on foreign societies from the traditional male opinion. Many of the things Lady Mary wrote about, from the bathhouse to the formal courts held by female nobles, were entirely inaccessible to any male writer. Even to this day it remains a unique piece of work, not to mention an enormously entertaining read. It’s a crying shame that Lady Mary Bute’s own uncomfortable relationship with her mother’s fame and frank writings saw her destroy her mother’s diary as too scandalous for publication. There are few who can claim to be both literary and medical pioneers; and though both saw many in Lady Mary’s lifetime denounce her as terrible both remain as the enduring legacy of a truly remarkable woman.

Pictures via wikimedia except where stated.

[1] Elizabeth’s maiden name of Evelyn was the source of the Earl’s somewhat misgendered forename.

[2] Not that Clotworthy Skeffington – this was his grandfather.

[3] With its themes of democracy resisting tyranny, the play was extremely popular with the American Founding Fathers. George Washington even had a performance put on to raise morale during the long winter his army spent at Valley Forge.

[4] Or so one story goes. Lady Mary’s attitude toward her posterity can best be described as “ambivalent”.

[5] He would go on to become friends with Frederick, Prince of Wales (and son of Mary’s old friend Queen Caroline) and as a result be appointed as tutor to the future George III. He even served briefly as Prime Minister after George became King.

[6] Though he was forced out the following year over his handling of peace terms with France after the Seven Years War.