Infinite Jest, the Movie

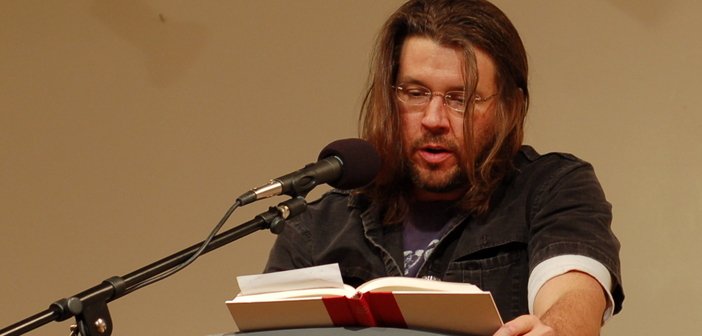

A movie has come out about a conversation between two writers. The two writers are talking about a very big book by one of the writers. The conversation is lengthy, being carried on over five days. The book is called Infinite Jest. Around 1996, Infinite Jest, written by David Foster Wallace, was published by Little Brown. It was hyped rather cleverly. The people at Little Brown really knew what they were doing. The publicists used little cards that were sent to other publications with the teaser phrases like ‘Infinite Writer’ and ‘Infinite Pleasure’. And how it worked. Infinite Jest sold at a phenomenal rate. It got glowing reviews. The critics went wild. Wallace was shocked and thrilled. This book had come out of a long dark time of suffering for Wallace. David Foster Wallace had been struggling with addiction and chronic depression for years. In fact his demons never left him, not really. David Wallace took his own life in 2008 after being taken off an antidepressant, Phenelzine, by his doctor. This was mainly because of its horrible side effects. Tragically, once he came off the meds, the depression came back with a vengeance. He had no children, being concerned that any offspring might inherit his illness. But the books, especially the book that is the subject of this piece, an offspring of sorts, abides.

Infinite Jest took a surprisingly short time to write, remembering it stretches to almost a thousand pages. Wallace had been working on it on and off for about six or seven years, and got deeply into it from 1991 or so onwards. The novel is both huge and encyclopaedic. It’s about addiction, pleasure, leisure, work, advertising, depression, education, entertainment, commerce, technology, tennis academies, the game of tennis, addiction recovery centres, parent-child relationships, the cross border relationship between the USA and Canada, and above all, the meaning of existence itself. It is set in a dystopic future North America, a single unified state comprising the United States, Canada, and Mexico, known as the Organization of North American Nations (O.N.A.N.) – a very obvious reference to, yes, onanism. Corporations purchase rights to naming years, so we have names and titles called ‘The Year of the Whopper’ and my personal favourite – ‘The Year of the Depend Adult Undergarment’, and so on. The book was instantly recognized as a classic, and more than being the clichéd embodiment of a dense unreadable classic that gets taught in universities and read by obligation, this was the kind of classic that was very funny, very clever, very entertaining, and aroused national interest despite the fact it was a hard read. People read it. They talked about it. It was discussed online and in reading groups. Since its arrival a veritable trove of analyses, online resources, and study groups have emerged around the text, some good and some not so good. It is, as mentioned, almost one thousand pages long and has three hundred footnotes. And what with the furore at the time, Wallace found himself having to cope with a phenomenal amount of attention. This was something he had very mixed feelings about. That being the case, there is no doubt the attention was well-deserved and the quality of the work was recognized from the first moment he began writing. When the editors at Little Brown received the first couple of hundred pages of the text, Michael Pietsch, Wallace’s editor at Little Brown commented that he wanted to get this book published more than he wanted to continue to breathe, such was the euphoria around the text as it emerged from Wallace’s brain.

Infinite Jest took a surprisingly short time to write, remembering it stretches to almost a thousand pages. Wallace had been working on it on and off for about six or seven years, and got deeply into it from 1991 or so onwards. The novel is both huge and encyclopaedic. It’s about addiction, pleasure, leisure, work, advertising, depression, education, entertainment, commerce, technology, tennis academies, the game of tennis, addiction recovery centres, parent-child relationships, the cross border relationship between the USA and Canada, and above all, the meaning of existence itself. It is set in a dystopic future North America, a single unified state comprising the United States, Canada, and Mexico, known as the Organization of North American Nations (O.N.A.N.) – a very obvious reference to, yes, onanism. Corporations purchase rights to naming years, so we have names and titles called ‘The Year of the Whopper’ and my personal favourite – ‘The Year of the Depend Adult Undergarment’, and so on. The book was instantly recognized as a classic, and more than being the clichéd embodiment of a dense unreadable classic that gets taught in universities and read by obligation, this was the kind of classic that was very funny, very clever, very entertaining, and aroused national interest despite the fact it was a hard read. People read it. They talked about it. It was discussed online and in reading groups. Since its arrival a veritable trove of analyses, online resources, and study groups have emerged around the text, some good and some not so good. It is, as mentioned, almost one thousand pages long and has three hundred footnotes. And what with the furore at the time, Wallace found himself having to cope with a phenomenal amount of attention. This was something he had very mixed feelings about. That being the case, there is no doubt the attention was well-deserved and the quality of the work was recognized from the first moment he began writing. When the editors at Little Brown received the first couple of hundred pages of the text, Michael Pietsch, Wallace’s editor at Little Brown commented that he wanted to get this book published more than he wanted to continue to breathe, such was the euphoria around the text as it emerged from Wallace’s brain.

[pullquote] The thing about Infinite Jest is that it is both universal in theme and subversive in nature. Its labyrinthine style, its use of neologisms, it’s almost mechanistic perfection of description is seductive, stimulating and hilarious at times to read. [/pullquote] The thing about Infinite Jest is that it is both universal in theme and subversive in nature. Its labyrinthine style, its use of neologisms, it’s almost mechanistic perfection of description is seductive, stimulating and hilarious at times to read. I remember the first time I picked up the book. It was the title that drew my attention. It reminded me of Shakespeare, but it took a minute or two before the reference clicked into place. The title is a reference to that great depressive of the theatre: The Prince of Denmark. Hamlet is at the grave yard (big surprise) with Horatio. He picks up his beloved childhood friend’s skull. Alas it was Yorick. He remembers his friend Yorick’s brilliant wit, and Hamlet, like Yorick the jester, speaks the truth without ego and without bias:

I knew him, Horatio; a fellow of Infinite Jest, of most excellent fancy; he hath borne me on his back a thousand times; and now, how abhorred in my imagination it is! My gorge rises at it. Here hung those lips that I have kissed I know not how oft. Where be your gibes now? Your gambols? Your songs? Your flashes of merriment, that were wont to set the table on a roar? Not one now, to mock your own grinning? Quite chap-fallen? (Hamlet Act V Sc1)

The central concern to Infinite Jest the book is also Hamlet’s central concern. The world has fallen out of joint. Beneath the infinite jest is infinite sorrow, a world of endless distractions, amusements and addiction, and eventual recovery without any real reason for going on. How is it, Wallace asks. How is it that we are filled with amusements, so much information, more information than we can ever cope with, so much technology, so many distractions and medicine and comforts, such availability of exquisite education, and yet at the core of it all there lies this emptiness, this empty-headedness, the same grinning skull that Hamlet holds, the sad grinning empty skull of Yorick, the end of all our thoughts and jokes and plans? Is this it? Is this as good as it gets? This is the end. This is the infinite jest of life. What does it all mean?

Infinite Jest is actually a movie. In the novel this movie called Infinite Jest is so entertaining that when you sit down and watch it you lose all sense of time and space.It’s so pleasurable, so entertaining, it’s something you never stop watching. You and the movie become one. It’s something akin to the ultimate drug. Think of the best online game ever, and go further. Add in the most addictive drug, and go further. This is the Infinite Jest. It’s akin to Monty Python’s killer joke, but instead of killing you because it’s so funny, it simply takes you over until you die. Naturally this is a really useful piece of art/technology. Everybody wants it and it goes missing. It holds within it a kind of ultimate power. Everybody wants this ring of power. There possibly can be only one. In the book, the movie – the Samizdat – was originally made by James Orin Incandenza Jnr, optics expert, film-maker, and founder of the Enfield Tennis Academy during a brief period of sobriety before he microwaved his head, thusly committing suicide. Leadership of the Academy passed on to his wife, the tall domineering perverse sexually voracious beautiful Avril Mondragon Incandenza. Her youngest son, the one who most reminds one of the author DFW, is Hal Incandenza, the pot smoking prodigiously gifted tennis player who has memorized the Oxford dictionary, has a love for all things intellectual, and is deeply unsure of his own gifts, and later of his own sanity. He winds up later on in the second of the two main institutions in the novel: The Ennet House Drug and Alcohol Recovery House, founded by Don Gateley, murderer, former Demerol addict, and thief, also (because of his size) at one stage an excellent football player. Another deep connection between the Academy and the clinic is the fascinating character of Madame Psychosis, or Joelle van Dyne, Lead character in the Infinite Jest movie, she resides at the clinic and was the main protagonist in the movie made by the founder of the ETA, J. O Incandenza. Hal, as his brilliant mind fails him and his addictions subsume him, winds up in the clinic.

The book takes place at a time in the future where even the measure of time is a corporate advertisement. This happened after President Limbaugh was assassinated and the calendar was sold to the highest bidder; Year of Glad, Year of Dairy Products from the American Heartland gives one a queasy feeling of hysterical disturbance. Add to this that much of the North East of the former United States and parts of Canada is a kind of wasteland – called the Great Concavity or Great Convexity – depending on where you are geographically, and it’s getting positively bizarre. Finally imagine you are living in the former USA and it is now a part of the new super state known as ONAN (Organization of North American Nations) or Canada, and one is getting into the nether regions of absurdity, rather like our present time. It also means that this is both a novel based on the present and extended into the future, as well as being a damning condemnation of the society that the author lives in. Like all powerful novelists, Wallace avoids propaganda and diatribes, and though one is touched by the horror of the emptiness his literary double, Hal Incandenza, experiences throughout the book, an emptiness one is tempted to postulate as a reflection of a certain absence of any kind of emotional or cultural core in the world in general. But this is never explicitly stated, one is never in the world of self-pitying, self-indulgent sentimentality. The humour is raw, clear, funny and intelligent.

[pullquote] Central to the writer’s concern are the nature and purpose of competition and excellence, the experience of addiction, family relationships, human isolation, and the meaning of suffering. [/pullquote] Central to the writer’s concern are the nature and purpose of competition and excellence, the experience of addiction, family relationships, human isolation, and the meaning of suffering. Infinite Jest is also about a father, James Orin Incandenza, trying to help his son, a son who feels nothing inside, no sense of any kind of interiority. Again we have a kind of Trinitarian structure, parallels with Father and Son, and then we have the spirit, the dynamic of a ghostly father seeing his son as a wraith, and trying to communicate something powerful and healing to him.

And then we have the unconventionality of the tome. We have a set of intersecting descriptions of lives that have neither a classic depiction of an opening drama, a series of unfolding plotlines, a compelling third act, or a cathartic moment at the end. It goes out with a gorgeous whimper. The novel draws to a close with the ghost of the father seeking to heal the son, Hal, through the Infinite Jest. It is subversive in the way which it mirrors how in life one rarely reaches a satisfactory conclusion to things one deeply seeks. The movie, the Infinite Jest, was made for and meant to work only on Hal, to make him feel something inside, akin to the electroshock treatment that Wallace himself received to try to get him out of the horrific depressions he suffered which eventually led to his suicide. If one does not have Hal’s psychology, one’s reaction to the movie is counter therapeutic. Instead of kick-starting one, it renders one hopelessly infinitely entertained and eventually catatonic. And then you die of jest. Sadly the movie fails to move Hal as he never sees it. So things get worse, and he winds up in the clinic. As he devolves into mute non communication, Madame Psychosis, or Joelle van Dyne, comes to see him and tells him of the furore around the movie, and Hal has nothing left except his tennis. His father’s ghost possesses Ortho “the darkness” Stice (a close friend of Hal who, chucklingly, is also known as the Wraithster, and also known as ‘the guy with the trusty huge head’) – so we have a bizarre scene of a dead father possessing his son’s opponent in the Whataburger Tennis Finals (and what a name!), a weird connection between father and son through a beloved sport, a kind of meaning and language and interface emerging in the balletic movement of racket and ball and players across a court in the game of tennis. So something true and lasting is achieved beyond the cold logic of winning or losing. Let’s hope Hal felt it, if little else.

So we have Infinite Jest, the book, which is a book largely about a movie that can kill you it’s so entertaining, and we have a movie about a book, The End of The Tour (2015), which is a movie about an extended conversation between two writers following the publication of the book named Infinite Jest. Check out all those isomorphisms. In the midst of all these infinitely recursive thought experiments, this is how the conversation between the two writers began. It began around the end of Wallace’s exhausting book tour in ‘96. Around this time David Lipsky, a novelist and short story writer, was working in Rolling Stone magazine as a contributing editor. One evening he picked up yet another glowing review of Infinite Jest. Reading it, he pitched an interview proposal to his editor in chief. The editor gave him the go ahead. But things went wrong. The Wallace Rolling Stone interview with Lipsky never happened. Lipsky was pulled from the interview to do a heroin story in Seattle. After that it became too late to do anything with the many interview tapes Lipsky had sitting in a shoe box in Lipsky’s apartment. After Wallace’s suicide in 2009, Lipsky dug up the tapes (as in the movie) and started listening to them anew. From this he started to write. And write. He wrote a poignant book. It was titled Although Of Course You End Up Becoming Yourself: A Road Trip with David Foster Wallace. It won several awards and was a best seller. The movie rights to it were pretty quickly picked up. The End of the Tour, which is a movie depiction of the five-day interview between the author (played Jesse Eisenberg) and Wallace (played by Jason Segel). Much of the extended conversations between the two writers make up the movie. In other words the central contention of the screenwriters is that these are tape transcripts making up the dialogue, aside for literary license in screenwriting a movie. Incidentally it’s interesting to note that the estate of David Foster Wallace disassociated themselves from the movie itself, and said they in no way regarded it as a tribute to the writer. This is not unusual in screen biopics, or even in literary biographies. Though it’s hard to see their problem with the film. It’s a clever and compassionate portrait of a lovable but deeply flawed writer, and a really compelling movie.

In the movie, Wallace is clearly experiencing a deep level of fatigue from all the attention and has been working on autopilot for a long time, dealing with endless signings and readings and interviews, and is living in fear that his depression might kick in at any time. He longs to get home to his dogs and his friends and the vast snowy expanses of Illinois and escape the furore around the 1996 publication of Infinite Jest. He also clearly resents the intrusion into the privacy of his life, despite the fact that it’s clear that his writerly ego is deeply massaged by all the attention (‘D’ya think Annie Lebiowitz will come down and take my picture?’). Lipsky reminds him over and over that ‘You did agree to the interview.’ And Wallace nods heavily and sighs and the dialogue goes on. It’s interesting too to realize what we are looking at when we look at the movie. We are looking at a movie about a book that is about a movie. And yet it’s actually ironic that by the time the interview between Lipsky and Wallace was going on, the actual movie rights to Infinite Jest were already sold, and Wallace was happy in the knowledge that it was highly likely that no one would ever make the movie. He said the movie would be something like thirteen hours long, with the kind of complexity of a Wagner Opera. Yet The End of the Tour is mostly about Infinite Jest.

In looking for the origins of the Infinite Jest, or the Samizdat (a process of disseminating documentation via underground channels), one encounters a mind boggling array of characters that parade through the novel, and there’s no escaping either the vastness or the detail with which Wallace writes. There are dozens of characters in this novel, a novel which focuses on the notions of addiction, vision (so many references to optics lenses, vistas, precise descriptions of machineries, the human body, tools, movies, screens – the author’s dextrous use of terms and colloquialisms are always a delight), family, depression, film, politics, and human isolation (the book is suffused with scenes of its characters alone in vast complexes, either taking drugs, or distracting themselves from their intense aloneness. Its size and complexity, its forensic descriptions of the absurdly unnecessary complex machinery of existence, implies and shows the infinite near inescapable matrix that is existence in the late twentieth century, the layers of competitive demands placed upon the young American to be someone, to become someone, to achieve, to become part of the world of demand and supply, to meet goals and to continue the work, the endless work of building the infinite complex of technocratic industrial economy, for the Academy and the Recovery clinic is the world writ small, and within this world there is an infinity. [pullquote] Wallace is obsessed with infinity, there are circles intersecting circles within the book, infinite skies and infinite tennis, infinite addictions, infinite pleasure, infinite subsidy. [/pullquote] Wallace is obsessed with infinity, there are circles intersecting circles within the book, infinite skies and infinite tennis, infinite addictions, infinite pleasure, infinite subsidy. In fact the sheer size of the text, its attempts at an encyclopaedic grasp of an entire world, its unendingness, also shows that no matter what, there is nothing at the end of everything but a further infinity. Somewhere within the labyrinth that is Infinite Jest is the answer that whispers within those half million odd words. And the answer is, there really is no answer. We go on. We hurt. We laugh. We cry. We look for love from each other. And life goes on.

Even at the end of the film, The End of the Tour, we see Lipsky’s character played by Jesse Eisenberg listening to the tapes of his conversations with Wallace over a decade before. He listens for a while to fragments, like a scene from Beckett’s Krapp’s Last Tape. He stops for a while, feeling the emotion choking him up. Then he listens a bit more. He is looking for something. He is returning to that point with which the movie began, the death of Wallace, his musing over those endless tapes, his realisation that no matter how many times he listens and re-listens to those tapes, remembering those magical conversations, conversations he said were the best of his life, conversations in shopping malls and planes and cars and restaurants and outside movie theatres and radio and television stations about writing and the novel and the meaning of contemporary American culture and the artist’s vision. Like the novel it was a puzzle, an infinite puzzle, and infinite intrigue,and something that would remain with him forever. It’s infinite, Dave. Infinity, and more.

Featured images via:

openculture.com

time.com

huffingtonpost.com

npr.org

the dissolve.com