Graphic Novels Matter | Fun Home by Alison Bechdel

Can a graphic novel be more expansive than a traditional novel? Is it possible for a book that probably has one word for every fifty that a conventional novel has, to be able to express more discursively than the latter? Fun Home proves that it is a possibility to be considered.

Alison Bechdel has packed themes of childhood, trauma, shame, feminism, homosexuality, representation, censorship and more in an autobiography that is only 232 pages long. For anyone who’s read this, there are no surprises that Bechdel was the recipient of the MacArthur “Genius” Award or that the novel was made into a hugely successful musical.

Bechdel has commented about the comics medium as a “triangulation” of word and image. She says that, “if languages could be unreliable and appearances could be deceiving, then maybe somehow by triangulating between them, you could manage to get a little closer to the truth…the space between the image and words was a powerful thing if you could figure out how to work with it.” And essentially, that is what the novel is about, Bechdel’s quest for truth. But getting to it is no easy task, for either Bechdel or for the reader.

The novel is a carefully crafted labyrinth that explores Bechdel’s life retroactively so that she can make sense of her father Bruce’s death, who was a closeted homosexual and an “ephebophile” (a person who has a sexual interest in late adolescents). The labyrinthine structure of this “tragicomedy” is a reflection of the house that Bechdel grew up in.

Her father’s frustration regarding his homosexuality manifested in his obsession of restoring the family house in order to put on a perfect façade to hide strained family relations within. While this gives much room to sensationalise an already incredible reality, as is true with a lot of autobiographies, Bechdel creates a stunning archival work that the reader can easily believe as an accurate representation of reality.

Autobiographies and objective truth

Lynda Barry, an American cartoonist who was a major contributor to underground comix, coined the term “autofictionalography” for a work that is based on real events with elements of fiction. To be fair, this could be said about all memoirs, as the objective truth is sometimes impossible or even inadvisable to express as it risks damaging one’s career or relations with friends or family members, as Daniel Mendelsohn notes here.

And even if one doesn’t bend the truth to protect oneself or dress it up to make oneself look good, objectivity is hard to achieve as memory itself is a subjective construction. It’s naturally hard to identify the exact moment where unbiased reality ends and one’s own perception of the truth begins.

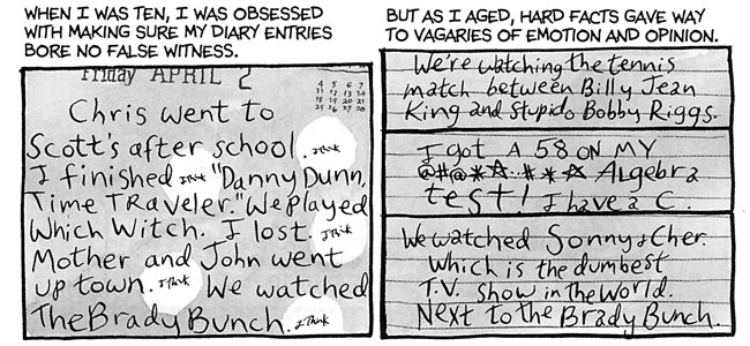

This is a fact that Bechdel constantly wrestles with throughout the novel. Suffering from an obsessive-compulsive disorder that had clearly manifested in her behaviour at an early age, a young Bechdel started keeping a diary to document her everyday life. Subconsciously noting her father’s atypical behaviour, and the way he constantly omitted the truth to hide his homosexuality, Bechdel’s sense of reality is shaken and her OCD exacerbates.

An adult Bechdel later muses, retroactively regarding her diary entries, “How did I know that the things I was writing were absolutely, objectively true? All I could speak for was my own perceptions, and perhaps not even those. My simple, declarative sentences began to strike me as hubristic at best, utter lies at worst…” Bechdel is therefore well aware of the shortcomings of memory and uses documentation such as photographs, letters and diary entries to get closer to objective reality.

Bechdel’s fixation on actuality even makes her go as far as replicating a pose from over 4000 photographs of herself imitating the different people in her book, including herself. This process of visualising evidence lends a truth to Bechdel’s work that would not be possible through any other medium. It gives a certain “straightforwardness”, as Dr Hillary Chute puts it, in expressing reality without sensationalising it.

Controversy and Fun Home

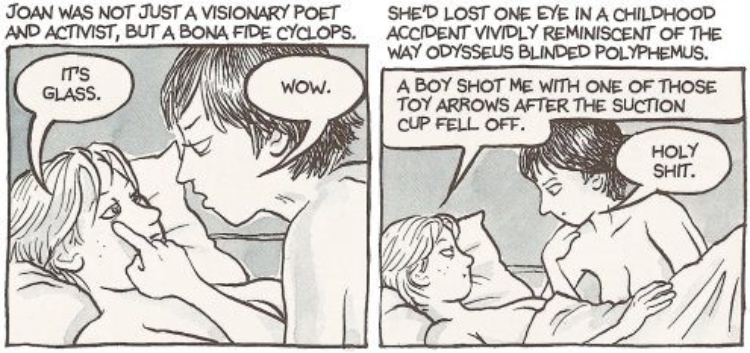

It is fair to say that while Fun Home had much acclaim as Bechdel effectively used the medium to express realities of homosexuality in a way that mere prose and photographs can’t capture, it also attracted much controversy for the same reason.

The book was assigned as recommended reading at Duke University in 2015 and freshman refused to read it. Brian Grasso, one of the freshmen who didn’t want to read it, wrote an article in the Washington Post about how the book was lesbian pornography, which was against his Christian morals. While the novel reveals intimate and sensitive aspects of Bechdel’s relationship with her girlfriend, the embodiment of these aspects through drawings can’t be called pornography, as none of the content was meant to excite.

A literary graphic novel

An expansive meditation on sexuality, Fun Home is a literary graphic novel that anyone with any interest in traditional literature would enjoy. One might assume that a graphic novel means weak writing, but Bechdel is as much of a prolific writer as she is a cartoonist.