Fortnightly Fiction | A Map Under the House

A Map Under the House by David O’Neill

A cat bowl, all matted hair and dried food, is against the wall in a corner of her kitchen. If the cat had any sense it would have started looking for food somewhere else but it waits, wide eyed, calling and nudging her for attention. Marianne ignores the bowl and the mewling; she is cooking food in her claustrophobic kitchen, fretting about the rubber seal on the oven that bubbles hot and cracks wide like a mouth when it cools. She worries too, but not much, about the holes that have started to appear in the bloated bin-bags stacked at the bottom of her garden. Mostly, she worries about the boys down the road and how little they seem to weigh and if they will like the turkey. My boys, she thinks. They appreciate me, even if nobody else does.

Marianne stuffs the turkey with oranges she stole from the market. When halved, she wipes juicy fingers down her skin-thin dressing gown and smiles at the whisper of fuzz growing at their core. She had intended on going back to pay but now she won’t. She was right to take them from that crook. Everyone is only interested in what they can grab for themselves these days. Except for me, she thinks. I look after my boys, my responsibilities. Later, when the turkey is slick and brown, she will apologise for leaving the bag of innards inside. She will assure them that it is fine to cut around the plastic drippings. I have done it a thousand times and it does no harm, she will say.

They whoop loudly, like monkeys, as she walks in heavy with food. It could sound false to some people, but not to Marianne. Her chest hurts with love for them and she almost drops her tray. They clear a space and take the turkey out of her hands. There isn’t much to their house; charity shop furniture and lopsided frames of cheap psychedelic prints. Still shaking off their student years, their money is better spent on clothes and promises of something or other with girls from the pub. One of them, tall and angry, stands to leave. He tuts loudly as he rounds the creaking, stained staircase to make sure they, and especially her, know how little time he has for this peculiar old thing.

‘Did I ever tell you about my dream?’ she says.

‘Don’t think so, Marianne. We’re all ears though’ says John.

John is stubby and anxious. He was the first to meet her when they moved in. He is the one that gave her a blanket and a mug when she mistook candles for a house fire and punched the paint from their door to wake them. He is the one that scooped slop back into bags the last time her garden was overrun with rats. Though she doesn’t admit to keeping favourites, he is hers and she loves the way he winks at her theatrically.

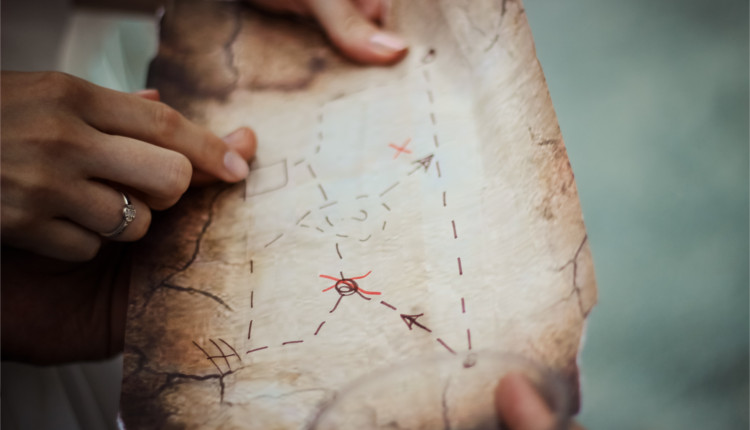

‘I’m going to sail away. One of these days.’ Marianne’s fingers splay wide as she talks, as if she is willing every word to matter. ‘I dreamed that there was a map buried under my house. It told me where I was to go’ she says. Marianne watches parents outside, picking children up from school and smiles as one of them, exploding and clumsy, tugs himself free from his mother’s hand and flaps in a mound of loud, crispy leaves. ‘Isn’t he wonderful? Independent fella’

‘What about this map, though?’ says John. ‘Do you believe it?’

‘I do, my love’ she says, turning back to the room. ‘I always thought I would see the world. I don’t know how to explain it. When my daughter was young, I felt a kind of listlessness. We fought; oh, how we fought. To my shame, I was relieved when she moved out. All those years though, it was almost like I was being tugged away on strong winds. I held on, for her, but I was stretched. Do you ever feel that way yourself?’

‘I’ll tell you what I know,’ says John. “That wind, it blew me here to you Marianne.’

He winks.

*

The kitchen is hot and loud with bacon and the windows blur with the breath of boiling water. Marianne flicks switches and turns potatoes, pirouetting from counter to table in a fluid, comfortable sweep. She never had a husband, or a man; she had a romance and she has a daughter. Sophie is like her mother in ways, with a sharp mind and tongue. Though she is barely fifteen, they argue about politics and books. She sells dioramas of scenes from her favourite films at the Saturday market on Clanbrassil Street so that she can pay a handyman to put a bolt lock on her bedroom door. She doesn’t like the flowers her mother plants in their garden, she dresses in oversized t-shirts to spite her and she already knows that when the time comes, she won’t look out the train window, teary-eyed and smothering under a tissue like the others, as her journey to college puts trees and fields and miles between them at last.

Before she reaches the kitchen, Marianne can hear her tramping through the hall, singing earphone-loud and bawdy like a drunk. Marianne pushes the salt and pepper shakers closer together, so they look like a family.

‘Why do you have this stupid old rug in the kitchen?’ Sophie asks.

‘I like it Sophie, and this is my house’

‘Our house’ says Sophie.

‘It will be our house when you pay to heat the radiators, my love’ Marianne says with a smile. It is Sophie’s house though, every block and slab, every cord of wood. The symphony of flowers in the garden, the kitten scratched rug which she loves to grumble about because it catches the leg of her dragging chair; it is all hers.

‘No earphones during dinner please’

Sophie pulls them free and they fall to the floor, still buzzing. The echo of songs slink between them but they both ignore it. Marianne smiles patiently at her daughter; Sophie scowls into her stew.

‘Do you ever get sick of this place?’

‘What do you mean, my love?’

‘Because I do’ Sophie continues. ‘I’m sick of this food, sick of this house with all those stupid paintings of boats in every fucking room and most of all, I’m sick of looking at your expectant, pathetic smile.’ Sophie knocks the salt shaker over and a slow arc of it trickles onto the tablecloth.

The kitchen is silent. Marianne scrapes Sophie’s uneaten food into the bin. The bag is full and bulging but she keeps scratching the fork over the china, the screech of it keeps her from screaming.

*

Sophie listens to her padding around downstairs. Her anger bubbles; deafening, as she hears her creaking from room to room. Always moving. Unable to let the walls breathe, even once. Instead, she clatters around, circulating air and humming incessantly. Sophie doesn’t know where this clarity came from, nor does she care. It’s not about clothes or flowers or armies of much-too-salty boiled ham. They do not fit and never have. The marrow that feeds their bones simply differs and no amount of clear-the-air talks over static spitting earphones will change that.

She has to leave. Now.

In the darkness, her face lit with its electric yellow, she batters her phone, looking for an open door or bed. Nothing at this hour. She checks under the mattress; sixty-three pounds. Not enough for a bedroom lock but it might get her down south, where he is. It’s late now, but maybe first thing, if she folds everything quietly, if she puts her shoes on in the driveway under the pre-dawn moon, if she can convince a B&B owner that she just looks young for her age and she gets that all the time, if he means what he has written in his letters.

*

Marianne opens the kitchen window and lets the smell of breakfast fill the garden. She is hoping that grease and caffeine will replace the eight hours of sleep she is owed. She will speak to Sophie; try again, once she has re-balanced. She might offer to pay for the lock. First, a cigarette amongst her plants to tack some sort of positive signpost to her day; a constant, in a sea of tipped over salt shakers.

The kitten follows her in from the garden, slithers through the closing door and, unnoticed by Marianne, slinks upstairs to sleep on Sophie’s empty bed.

*

The turkey went straight outside, bypassing the flipped-lid bin in their kitchen. The hot, singed smell hung around for much of the weekend though, echoing still as he packed a lunch on Monday morning. John walked home from work later that day. Late summer was a good influence on his part of the city. It was when sounds bounced through the streets easily and people said hello to each other in passing. He thought about stopping for a pint but carried on; he had been sitting all day and didn’t want to start again now.

The house was quiet as usual. Weekend boys that preferred their own space by Monday. A sort of amicable ignorance held for the first few days of each week; it suited them all. He weaved between bags and washing, stepped over outstretched legs, ironed shirts and read pages of a political thriller that made his head heavy. It was dark, but still warm so he pulled the door behind him and went outside to smoke on the thick block steps.

He flicked his cigarette onto the street and looked over at Marianne’s place. They would have to buy her something in return for all that food. It didn’t matter if they threw it out, he felt guilty that she spent so much on them. If the others gave her a bit more attention instead of sneering and doing those stupid wide-fingered impressions behind her back. If they just fucking listened. I might not feel as guilty. Her lights were on, a brilliant yellow throwing long rectangles onto the road. Marianne watched television in the dark, stuttering white like a thunderstorm in her sitting room; she didn’t turn on houselights. He walked over.

The cat stood on the coffee table, eating from a crudely torn bag of food, enough for a week if he didn’t eat too fast. The house was untouched; ramshackle, crumbling, but no more than usual. A low groan of voices turned out to be radio presenters, monotonous and grey, the unit almost tuned so that their words came with a crunch. John looked into the tar of the back garden, he could hear the scraping of rats. When he turned the light on, he saw it.

The green kitchen rug, rolled loosely, stood like a soldier against the press, crumbs and stains on its fuzz. The floor was exposed and though wooden and shabby, it was spectacular. He saw a hooked crescent moon, a wide triangular sail, and stars; so many stars. It was painted crudely but with a sort of tenderness; almost childlike. The boat was being cinched over a flurry of mountains. It was teetering, this thing, unsure of itself. Every inch of the floor was humming with colour, fantastic and dreamlike.

Marianne had stood on this most of her life as it called her, pushed her, willed her away, until she had no choice other than to expose it and follow, wherever it took her. She might be back, pushing trays of meat or fruit on them in her usual detached way. She might splay her fingers wide with a new story of travel and wind. She might scream at the delights she has been waiting almost fifty years to see, or remember.

I hope, John thought. I hope we don’t see her for a while.