Art Encounters | How To Get There…

‘I grabbed you by the gilded beams,

That’s what tradition means.’

The Smiths, I Started Something I Couldn’t Finish.

Last year, having skipped over it during my undergraduate years, I read Margaret Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale. One of my adult goals is to maintain an interest in literature that has taken classic form, and Atwood’s dystopian epic is one such novel. I found it eerie and discomforting, not least because of the silent grief that accompanies infertility, but because of the well publicised echoes of contemporary times in the novel. Then, when the TV series started to gather momentum critically, I watched the first episode. I can’t say I disliked this episode. On the contrary, I liked it a lot. But it made me angry. I found it too much. I intend to go back to the series again but I kind of wanted to explore the origins of the response I had, around what was brought up in the episode, before returning to it. I want to explore the affect of anger.

On one level it’s easy to locate the origin of my anger; my anger comes from the subjugation of people by religion. When I saw the pictures of Irish women protesting the Eight Amendment in newspapers, all of whom were wearing the same costumes the women wear in The Handmaid’s Tale, it got me thinking about Atwood’s novel and the television adaptation of it again; it also got me thinking about the shit going down in the TV series and the shit going down in the country I live in. And it got me thinking about patriarchy in a much more general sense. Because I’m a bloke, there’s a view that I don’t have to think about the stuff going down in The Handmaid’s Tale too much; that the everyday effects of patriarchy don’t impinge on me. And to a certain degree that’s true. But when I get angry I like to know where I should direct this anger precisely. And the reason I like to know this is because, as a psychologist once told me years ago, anger turned inwards is a definitive recipe for trouble.

Rewind to June 2016. I have just given a homily in the Cathedral in Tuam for my father’s funeral mass. In the speech I referred to my Dad’s involvement in the development of family planning in Ireland; in particular the Galway Family Planning Clinic.* It seemed – at once – natural for me to make reference to these events because going to ‘the clinic’ with my Dad was a lush memory from my childhood. What largely passed me by as a kid is the context around which this memory formed: the lurking threat of arrest, the religious protestors who campaigned against the clinic; that most of the people involved in setting up the clinic were professional volunteers (every time I pass O’Briens newsagent on Shop Street I remember walking up the streets to look at the magazines as a kid, while waiting intently on my Dad finishing). It was almost natural for me to mention this. What I didn’t expect when writing the homily was the reaction I received, when a number of women specifically came up to thank me for making reference to this thorny historical moment in the Cathedral. They thanked me for celebrating this part of my father’s life – in a church, in 2016.

The weird thing for me, however, was I didn’t really think of what I was doing. It was just a memory of childhood. In the interim years, like so many, I had become accustomed to legal contraception (and family planning generally), and anything otherwise seemed almost absurd. In so many instances, the contours of this New Ireland had become the norm. It is precisely when things become the norm, however, and we find it hard to think otherwise, we should push ourselves to do so; think how things might have been. In this sense, we take our cue from writers like Atwood who imagine alternative futures and sometimes, alternative pasts, to explore threats in our midst. This means we should take our cue from writers who offer the means to imagine what kind of country we might be living in now had certain actions not been taken; had such battles not been won? And this is not because an imagination is just a source of comfort, but because we can use it to confront the state of our present.

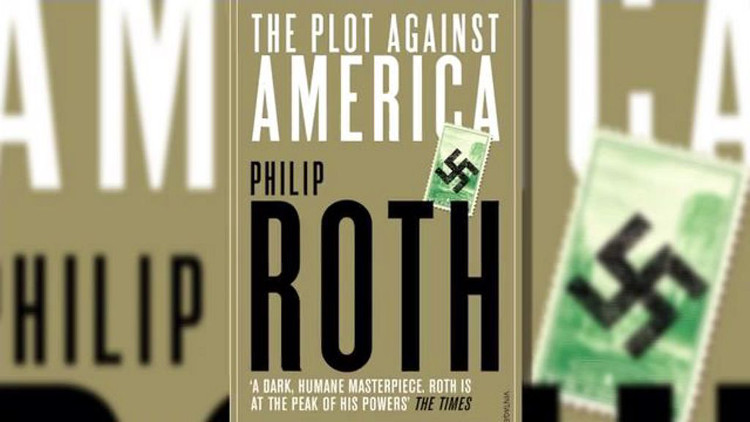

Philip Roth’s bizarre yet nonetheless intriguing novel The Plot Against America does something similar. Roth imagines the past had the anti-Semitic pro-fascist politician Charles Lindbergh won the American presidential leader election ahead of Franklin D. Roosevelt. In Roth’s novel, Lindbergh begins his presidency by signing a pact with Hitler, promising that the US will not interfere with the Nazi’s plans for European expansion. This sets off a train of events that impact upon Roth’s own family and friends in the novel, the reverberations of which are felt over the course of the period that Lindbergh is in office: from members of his family having to move to Canada, to his best friend moving to Kentucky where his mother is killed by a resurgent Klu Klax Klan. Reading Roth’s novel (and indeed Atwood’s novel) today, when the current US presidency often seems like some weird alternative history has somehow been realised (part of an equally bizarre plot), we learn of the dangers of a fascism that was there for the ripening. A simple turn of events, had people not voted in the way they did, had they not stood up to the fascism in their midst, could have led to a whole different trajectory to Roth’s own life and indeed the American people. The novel itself reminds us of our own agency, of our own responsibility to the present.

I then started thinking of those days waiting on my Dad to finish work, with the threat of arrest hanging over the whole project, and an alternative outcome had my father been arrested. Our family would have had to emigrate, move back to Manchester perhaps (where I was born and spent my early years). I would have been educated in the UK and would see myself as both British and Irish. I would talk about that country where people still have trouble accessing contraception and a quasi-religious oligarchy runs the country; where a once fought-for separation between state and church remains a pipe dream. In this alternative history, I thank my lucky stars I escaped. Like a modern day refugee who has got out in time, I maintain a weird relationship with the motherland. But in my alternative history, the other side wins.

I had been daydreaming about this past, but also how I would go about finishing this article I’m writing, tie this stuff together into something meaningful, when I realised I had to go to pick my son Karl from school. I was late. It was only when driving that things started falling into place: the Atwood stuff, the Roth stuff, and my imaginary past. Suddenly there was a thread. Like the majority of state-funded schools in Ireland, the school I was driving towards has an official religion: Catholicism. In Catholicism, women are excluded from positions of power. Put simply, the official religion is based on a system of power where some people can gain decision-making powers while others can’t on the basis of their genetic make-up (in this case gender).

There is no need to repeat the arguments against this situation. They are well documented. Change is being hard fought for in this regard. But as I drove I suddenly started to think of the corrosive nature of this exclusion. I suddenly thought that maybe the biggest problem wasn’t belief in such precarious stuff as virgin pregnancies. Most kids are savvy enough to recognise this as mumbo jumbo. It is not belief itself that is the real problem; it’s the organisation that teaches this belief. The Catholic Church excludes women from power. And excluding people on the basis of gender is, put simply, fascist. Suddenly the state of Gilead in The Handmaid’s Tale isn’t so far away. And here’s the thing that got me most as I drove; now, with loads of crazy shit going on, surely there’s an added urgency to call out the fascism in our midst. It is incumbent upon us to call out the principle of excluding anyone from power as intrinsically fascist; not just in organisations like the Catholic Church but every facet of life. So there I was, driving, thinking about an organisation that cultivates exclusion as having all this power. In Ireland, we’re basically outsourcing our morality to a Church that excludes based on gender. How has this happened?

Back to that episode of The Handmaid’s Tale and my response. ‘The major enemy,’ Michel Foucault once wrote, ‘the strategic adversary, is fascism And not only historical fascism, the fascism of Hitler and Mussolini— which was able to mobilise and use the desire of the masses so effectively — but also the fascism in us all, in our heads and in our everyday behaviour, the fascism that causes us to love power, to desire the very thing that dominates and exploits us.’ For Foucault, fascism can seep into all social structures. Indeed, Foucault spent much of his life exposing the micro functioning of fascism in social organisations he calls discourses. His pressing concern is to explore the way we become invested in our own subjugation; how people end up participating in their own exploitation. When turning this analysis upon the school system in Ireland, and asking similar questions of it, we are led to question why such fascism isn’t called out for what it is? For a significant percentage of the population persist in supporting an organisation that excludes on the basis of genetic make-up alone. Hence we have a country where a majority votes for marriage equality while the state that they also vote for continues to prop up an organisation that doesn’t even recognise gender equality. Maybe I should stop the car and think about this again.

‘Dad, how come there’s no women priests?’ is that question that irks you every time. It gets tougher as they get older: ‘Dad, we learnt about our women presidents Mary Robinson and Mary McAleese in school today. How come they can’t be Pope?’ Offering an honest answer, an answer like ‘they’re not allowed to’ brings the added worry your child will process this information in the following terms ‘men have power, women don’t.’ Hence, the principle of exclusion is internalised as a norm. And when we confront a world of norms like this we enter the world of the fascist, the world that begins by fostering the principle that people of one type and not people of another type can hold power. Recognise this anywhere? Of course you do. It is the foundational principle, the kernel that grows into a political system that dominates women in The Handmaid’s Tale. It is also the kernel of power growing into an oppressive system in The Plot Against America when Lindbergh suddenly disappears.

Epilogue:

‘Listen to this song Karl.’

‘Who’s it by?’

‘A singer called Bjork.’

‘Who’s she?’

‘She comes from Iceland.’

‘Where’s that?’

‘It’s a place like where Mammy comes from.’

‘It’s weird.’

‘This song is from her new album Utopia. It’s called ‘Tabula Rasa‘.

‘Hurry up. I’m hungry.’

‘Listen to the words ‘tabula rasa, for my children.’

‘What does that mean?’

‘Utopia is a place where everyone is equal.’

‘No, the other thing.’

‘Tabula Rasa?

‘Yeah.’

How to get there.’

‘Cool.’

*A strange coincidence occurred as I was writing this article. My attention was drawn to an academic article concerning this topic that is just published and is dedicated to my father: ‘On the Perimeter of the Lawful’: Enduring Illegality in the Irish Family Planning Movement, 1972–1985’ (by Emilie Cloatre and Máiréad Enright).