William Chidley, Would-Be Sexual Reformer

Warning: William Chidley was a man with unusual views on sex and sexuality. As a result, in order to explain these views this episode of Terrible People from History uses somewhat more graphic language than you might normally expect from a historical article, and could be considered NSFW.

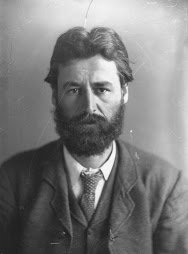

William Chidley was born in 1860, presumably. He was a foundling, abandoned by his birth mother, and as an infant he was adopted by the Chidleys. John James Chidley was a photographer, who was at the time living in Kew in Melbourne. [1] We know this because he was called as a witness in a divorce case the following year. He had hired a young woman to become governess for young William and his (also adopted) siblings, but discovered after a few months that she was pregnant due to an affair with her former employer. Even at this early age, sex was disrupting young William’s life. John and his wife Maria adopted five children in total – William, Stanley, Ada, Ellen and Jane. (Ellen and Jane were sisters by blood as well as adoption – the children of a bankrupted couple named Sherry.) John had been a bookseller in London, but emigrated to Australia (possibly due to his being sued for publishing a plagiarised cookbook). He and Maria were an eccentric couple, noted for their vegetarianism and for being followers of the teachings of Emanuel Swedenborg. Swedenborg was an 18th century Swedish philosopher who believed that Jesus had appeared to him personally to show him the secrets of Heaven and Earth. His followers were generally considered eccentric, but harmless and well-meaning – exactly the sort to adopt five lost children when they could have none of their own.

One extremely formative incident in William’s childhood was an attack of priapism, a medical condition where he suffered a prolonged and painful erection. Young William was deeply embarrassed by this, especially when his parents were forced to call in a doctor. In his posthumously published autobiography, he comments:

I remember my rage and shame, and Mother’s kind words – even the amused look in the young doctor’s eyes as he dabbed at ‘it’ with a sponge, which increased my rage so that I kicked at him.

What William does not document is what the long term effects of this incident were. Not only is priapism often a symptom of a more serious underlying condition, but the condition itself can (if untreated, and no treatment was available at the time) cause permanent damage to the genitalia – something which may have contributed to some of William’s later ideas and fixations.

William was apprenticed to an architect as a young man, but he found the work too dry and dull for him. He abandoned the trade, and dropped out to be an artist. His mother Maria died in 1878, which could be what prompted this rethink of his priorities. His father would eventually remarry to a woman named Matilda some time later. William made his living as a street artist, travelling from city to city. In 1882 he and a friend named Arthur Saddler were in a cab travelling through Adelaide when they saw a man beating a woman up. Arthur stopped the cab, jumped out and went to her aid. The man (named Thomas Maloney) proved too much for him, so he called William to his aid and the two of them knocked the man over. He retreated and started throwing stones at them, until a friend of the woman’s arrived and attacked him. Thomas fell, and he did not get up again. Those on the scene made themselves scarce, but Arthur and William were recognised by someone in the crowd. They were tracked down by the police, arrested and charged with manslaughter. Though they were acquitted (Maloney had died from hitting his head on the ground, and there was no evidence that they had caused this) the event added to William’s perception of the world as a hateful and violent place.

After his release from prison, William joined a theatre company in Sydney. It was here that he met a pretty young actress named Ada Grantleigh. This was a stage name, one she had adopted on joining her previous theatrical company. [1] Ada’s legal name was Thoms, that of a husband she had married in 1881 aged eighteen and left shortly thereafter. Her maiden name was not recorded – she took Grantleigh as a surname in gratitude to a theatre manager who had helped her escape her husband. Ada took a fancy to William, and though initially he resisted her advances she persisted. The two began an on-again, off-again relationship that lasted for the next twenty-five years. Both were heavy drinkers, and their libidos were extremely mismatched – William’s sex drive was highly repressed, while Ada wound up frequently being unfaithful. In one notable incident (recorded in his memoirs) she left on a business trip to Melbourne with a young singer named Gussie Freudenberg. Gussie (short for Augusta) was a tall, dark woman whose parents were German immigrants. Ada and William had met her a few times in various theatre engagements, and William had liked her. He was happy that Ada had company on her trip, but after a few months she showed no sign of returning. Then she stopped writing. William travelled to Melbourne and was directed to their lodgings above a fruit shop by a chorus girl who commented:

Oh, are you her husband? I know her. I have seen them together. Why don’t you keep your wife with you?

William was disquieted by this (and recalled vague rumours from his childhood of a great scandal where one of his father’s friend’s wife was found in bed with another woman). Still, he played it cool. He moved into the apartment with Ada, and Gussie took another room in the same building along with a ballet girl. William wrote:

I have seen young men escort her home after the theatre, but she would leave them indifferently and retire with her friend, eyeing her as a cat does a mouse. Ada was always in tears until Miss Freudenberg went away, she and her pretty friend.

Eventually William and Ada went back to Adelaide. Some time later he heard that Gussie was in town, but he also heard that she was engaged to be married and decided that he must have been mistaken about her sexuality. Then he met her and Ada travelling together on a tram. They asked him when he would be home and he said he would be late, but then in a fit of suspicion he followed them back to his house. He found the door locked and bolted, and when he knocked for admittance it was eventually answered by Gussie “half dressed, in her petticoats and pale as death”. He ordered her out of the house in a rage. Ada and he made up their differences, and though William writes of the whole affair in a bit of an outraged tone, he did admit to “a sort of prurient curiosity”.

An opportunity to indulge this curiosity came during one of his separations from Ada, when he met a tall and striking woman in the street. Her name was Alma, and William immediately developed an unrequited affection for her. The two became acquaintances, though nothing more, and William became convinced that Alma was

[O]ne of those girls, like Miss Freudenberg, who give way to inverted practises.

His disapproval led to the end of their acquaintance, though he became briefly obsessed with the thought of “saving” her. It wasn’t her homosexuality he was saving her from – William was gradually becoming convinced that sexual activity in any form was deeply detrimental to people’s health. (William had his own homosexual episodes, which he regarded with just as much shame as his heterosexual episodes.) He explained as much in a letter he wrote to Alma. She, somewhat, understandably, wrote back asking him to stop sending her letters. William escalated by proposing marriage, which she (naturally) refused. However they do seem to have kept in touch – he visited her in Sydney and made her a gift of five pounds, but was disgusted when she took it and “eloped to Sydney with a girl”. They did continue their acquaintance for a while, but eventually she cut contact with him.

William’s father John Chidley entered the news in 1888 when he designed a heavier than air flying machine – a bamboo and canvas glider. He planned to show it to the public in March, but an unexpected storm sent the machine over and injured him. A news cable published across the country said he had received “a severe shaking”. John continued to work on his aircraft until his death in 1890. He left the “flying machine” to William’s brother Stanley. Perhaps out of fear that William would squander his inheritance, he told the executor to invest it and give William access only to the interest. From the will it seems that Matilda outlived her husband, that Ellen was a widow, and that William’s other sisters Ada and Jane had either been disowned or had passed on. William’s family situation changed once again in 1891, when Ada (his lover, not his sister) came home from the hospital with a boy named Donald. William believed the boy was his, and it was not until nine years later that Ada told him the truth. His son had died in the hospital, but so had Donald’s mother. With no family to claim him, the hospital had allowed her to take the boy home. Not technically legal, but common enough practice. William’s response to this is unknown. Though he later claimed on official forms to have no children, this may have been an attempt to let Donald keep his anonymity.

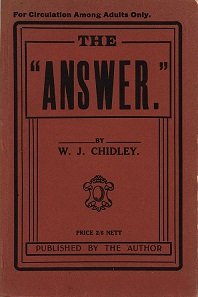

Exactly when William first formulated The Answer is hard to pin down. He’d clearly been forming his thoughts about sex and sexuality for some time. For example, in 1899 he had begun a correspondence with Havelock Ellis, a writer on the psychology of sex who was a former resident of Sydney. However the key incident seems to have come on a spring night, when William awoke to find that his flaccid penis had somehow found its way into Ada’s vagina as he slept. He doesn’t seem to have thought much of the incident at first, but it gradually came to hold a Zahir-like fascination for him. William had always been tormented by his sexual drive, but had equally begun to believe that any sexual activity was extremely bad for your health (and also, bizarrely, gave you a unibrow). In addition his childhood illness may have damaged him to the point where erections were painful for him. For whatever reasons his experience led him to think that it was not sex itself that was harmful, but rather sex involving erections (which he referred to as “the crowbar method”) where the tumescence drained the man and damaged the woman. [2] His theory was that in the spring (the time when other mammals came into season) the woman’s vagina would somehow transform and create a natural vacuum, sucking in the man’s penis without any need for an erection. If all sex was like this, William believed, then humanity could be saved.

Ada died in a hospital in 1908, after several years of illness. William blamed himself (somewhat irrationally) for her death, and wrote to Ellis:

Part of myself has gone…I have failed as far as she and I are concerned. It is only the thought of others that keeps me alive now.

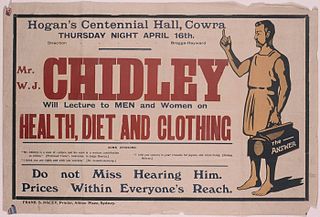

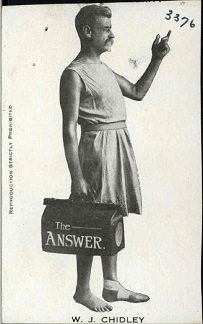

It was for those others that William had written a book, which he called simply The Answer. In it he spoke of the virtues of loose-fitting clothing, a vegetarian diet, and his revolutionary new method of sexual intercourse. Unsurprisingly he found it difficult to secure a publisher, and he had been trying to get the book (in one form or another) out for the last ten years. Ada’s death galvanised him, however, and he decided to pay for its publication himself. With these copies in hand he strode out into the streets of Melbourne, dressed in a loose-fitting toga. And people took notice.

The press were unsure how to cover “Chidley’s Crusade”. The Melbourne Herald declared he “was not a lunatic, but a scholar and philosopher, who had the courage of his convictions”. The Adelaide Register commented that “his main theory and the arguments in support could be discussed in medical journals only”. The police were less conflicted, and on the 11th of May 1911 he found himself in court for the first time charged with “Abusive Behaviour”. One paper described the scene:

His tanned body and general physique gave him the semblance of a Greco-Roman warrior, as he stood eyeing the bench in an unconcerned manner, and on his chest and back were placarded the words. ‘The Answer’.

He was fined eight shillings, and the judge dismissed him as a “faddist”. As they were to find out though, for William this was no mere fad. In October 1911 he and two men who had helped him get his books into bookstores were charged with distributing obscene literature. He was fined five guineas, but this did nothing to discourage him. By August 1912 the authorities had had enough. They declared him legally insane and had him confined in the Callan Park Hospital.

This clear abuse of the laws on confining the mentally ill caused outrage, and though nobody really agreed with William’s Answer he was still vigorously defended by free speech advocates and those who sought to curb the authoritarian state of the time. Even cultural conservatives (such as the poet Archibald Strong, who would go on to be Chief Film Censor) spoke out in his defence. The Answer may have been shockingly frank, but it definitely failed to meet the legal definition of obscenity. Similarly William Chidley may have had odd beliefs, but he failed to meet the legal definition of insane. He was released in October of 1912, but by December the authorities had once again imprisoned him. This cycle repeated over the next few years, and to many William became a symbol of Australian individualism – the right to be a crank in your own way. [3] But to others his refusal to conform and to keep his head down was a challenge that could not be tolerated. In between fell the opinion that if he had broken the law then prosecute him for that, but that if the evidence was too flimsy for such a course then the abuse of lunacy laws to silence him was intolerable.

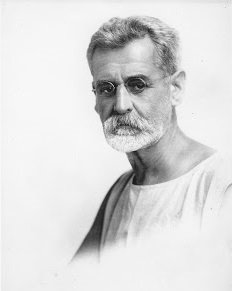

Though William didn’t meet the legal definition of insanity, he definitely was not a well man. The obsessions that had driven him to write “The Answer” now drove him to preach his beliefs, and no amount of persecution could make him stop. However the fact that he met with either ridicule or dismissal cut him more deeply, and he gradually became more and more depressed. By 1916 Australia was facing riots over conscription, and few had time for him any more. Some of his supporters talked of offering him passage to America or Canada, leading to official statements from those countries that he would be refused entry. In September 1916 William was arrested for the final time, having broken a parole that he would address no public gatherings. This seems to have been the final straw for a man already on the edge. On three separate occasions in October, while imprisoned, he attempted suicide – the last time, by getting hold of a can of kerosene and setting himself ablaze. He was severely burned, and barely survived. Over the next few months reports on his health appeared in the papers, and many expressed a hope that “his familiar figure will be seen again in Sydney streets before long”. By mid-December he had recovered enough from his burns to be back up and about, though he was still an inmate at Callan Park. But on the morning of 21st December he suffered a heart attack and collapsed. By that afternoon he was dead.

William Chidley’s death brought public sympathy firmly onto his side, and gave a tragic poignancy to the last five years of persecution. William’s time in the public eye did a great deal to reduce the restrictions on free speech in Australia, and to bring discussion of sexual matters more into the mainstream http://insidestory.org.au/william-chidleys-answer-to-the-sex-problem . But equally significant was his impact on the discussion of mental illness. The obvious difference between this harmless eccentric and the dangerous “lunatic” the law was designed to restrain helped to demolish the credibility of the stereotype, and to remove some of the stigma associated with mental illness. The question of “Is Chidley Sane?” brought a debate over what “sanity” and “insanity” meant into the public discourse. The words of one letter written to the newspapers in November 1916 are worth repeating:

Few people are free from mental illness just as few are free from physical illness. The majority of us go about our business nevertheless, but in some cases the mental illness, and in others the physical illness, is such as to require treatment in hospital. This more humane view of mental disorder relieves these whose misfortune it is to be incapacitated mentally from the stigma of insanity.

Most of what we know of William and his state of mind came from his autobiography, entitled Confessions, which he sent to his friend Havelock Ellis before his death. In 1935 Ellis donated the manuscript to the State Library of New South Wales, and it languished there until Sally McInerny rediscovered it and had it published in 1977. It remains an unusually frank portrait of life in 19th century Australia’s fringe culture. It also provides a great deal of insight into William himself, and helps to show how a brilliant mind was fractured over the years. It’s a sad fact that even today, a hundred years later, those who suffer from from mental illness in the public eye are often as ridiculed as poor William Chidley.

Images via wikimedia except where stated.

[1] One notable play put on by that company revolved around the lives of Jack Sheppard and our old friend Jonathan Wild

[2] Probably not best to try to figure out how this tied into the lesbians.

[3] He also became a fancy dress costume, just as Amy Bock had.