Tiger and Boyle Roche, Contrasting Irish Brothers

Nature versus nurture is one of the oldest debates there is. Are we predetermined to become who we become, or is it the world we encounter that shapes us into who we are? The story of David (”Tiger”) Roche and Boyle Roche seems almost tailor-made to test these hypotheses: brothers both born into luxury, who set foot on the same road but followed it to very different destinations. Or did they?

David was the elder of the two, though it’s unclear as to whether he was the eldest or second son of Jordan and Ellen Roche. (The third Roche brother didn’t survive to adulthood.) He was born in 1729 as a member of one of the noble Protestant English families resident in Ireland for centuries. The Roches were descended from a Flemish knight named Godebert of Rhos who had settled in England and whose son Richard was actually the first Norman knight to visit Ireland (in 1167). By the 18th century the family held the Viscountcy of Fermoy, and though Jordan was of the junior branch he shared in the reflection of that aristocratic glory. His grandfather had been Mayor of Limerick four times.

As a result of this David was given a first-class education in Dublin (where he was born), though his parents seem to have moved to Galway by 1736. That’s where his younger brother Boyle was born. Like David, Boyle received a first-class education. Both their lives were shocked when their father died sometime during David’s teenage years. Their mother returned to England, but David at least remained in Ireland. This lack of a father’s advice may have been why the young man made the greatest mistake of his life in 1745.

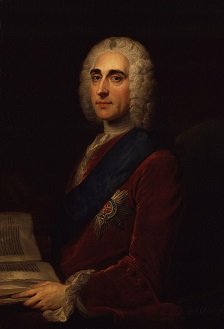

The Lord-Lieutenant of Ireland at the time was Philip Stanhope, the Earl of Chesterfield. Young David came to his attention, and he was impressed enough by the young man’s intelligence and accomplishments to offer to sponsor him with a commission in the army. This would have been a major boost for a young sixteen year old, but David was persuaded by his friends to turn down the offer. (There are some suggestions that it may have been declined on his behalf by his “friends” in such a way that David could not go back on it.) As a result David’s life instead became one of drinking and street-brawling, a course that eventually led to disaster.

In 1753 David Roche was involved, in some way, in the death of a Dublin watchman. He and his drunken friends had kicked up a riot, the watchman had tried to calm it down, and somebody had murdered him. A warrant was sworn out against David as an accessory and so the twenty-three year old had to flee first the city and then the country, heading across the Atlantic to the English colonies in the New World. He was there when a war broke out between Britain and France, a conflict that spun out into what some have described as the first real “World War”. It was this war that would see the destiny of the Roche brothers cross once again.

It was in North America that conflict first broke out between the British and the French, when a troop of British soldiers led by Lieutenant Colonel George Washington (yes, that one) wiped out a French force who had been preventing the building of a British fort. This led to an escalation of back and forth attacks that soon led to outright war. David Roche was among the colonists who volunteered to join the local militia and take part in these battles. Back in the British Isles his brother Boyle had joined the regular British army, and was part of the forces sent across to support the colonists. If David had taken that commission from the Earl of Chesterfield, he might have been among them as well.

David did earn himself a commission on his own merit, as part of the provincial militia. Confusingly some of the accounts say that he originally fought on the French side, but it was in the British forces that he was commissioned. (It’s possible that he fought as a mercenary for the French against the local tribes before the war.) He was noted for his spirit by Lieutenant Colonel Eyre Massey, the commander of his regiment and an Irishman like him. This made it all the more shocking to the commander when David was accused of theft from one of his fellow officers.

A hunting gun belonging to this officer had gone missing, and he went looking for it. Someone told him that David had recently acquired such a gun, so the officer got the authority to search his baggage. Sure enough, David had the gun. He insisted that he had bought the gun from a Corporal Bourke, who in turn denied completely that he had ever seen the gun. The matter was taken to a court martial, and David was found guilty of theft. Given his previous good conduct, he was merely given a dishonorable discharge. David was infuriated by the verdict and first challenged his accuser to a duel. This was refused, on the grounds that David had forfeited his status as a gentleman and wasn’t worth dueling. This drove David into a blind fury. He headed out to where he knew Bourke was standing guard, drew his sword and attacked him. Bourke managed to defend himself until the other guards overpowered David and took his sword. Then David broke free. He leaped at Bourke and buried his teeth in the man’s throat, nearly crushing his windpipe. When he was pulled off him he tore a chunk of the man’s flesh away with him. This was how he earned the nickname “Tiger”.

While David was suffering this disgrace, Boyle was earning himself honour. He was a lieutenant in the 27th Foot regiment, who had gone to America to fight alongside the colonists. Boyle was stationed in Fort Edward on the Hudson river, where he set out in the winter of 1758 to scout alongside the famous local unit known as “Rogers’ Rangers”. The scouting unit were ambushed by a group of Indians fighting for the French and defeated, and Boyle was captured. He was taken prisoner and held prisoner in Fort Carillon, the main French fort defending the Canadian border. He wasn’t mistreated, and was given the respect “due an officer”; and he was even allowed to send letters to his friends in the British army to let them know he still lived.

During the time that Boyle was held captive by the French, Tiger was in vain trying to clear his name. After his attack on Bourke he had been left behind in the wilderness by the army and forced to make his own way back to civilization, only to find that his infamy had preceded him. He joined in the assault on Fort Carillon, and was among the troops who captured the fort. He fought bravely in the battle and came to the attention of the officers, but the story of his alleged theft had traveled before him and rather than being lauded he was ordered to leave. There’s no record of whether the two brothers even knew that they were in the same city before Tiger was sent away.

On Boyle’s release he joined the forces led by General Wolfe who laid siege to the French-Canadian city of Quebec in 1759. This was a bloody battle that led to the death of the generals on both sides of the conflict, but it was the British who won the day and took the city. Their victory here effectively ended French control of Canada. Though the French still held Montreal and the war continued for another year it was almost a formulaic exercise for the British to continue on and conquer the remainder. When the Treaty of Paris eventually ceded all North American territory held by the French to Britain it was really just a legal recognition of the reality that began in Quebec.

After the battle of Carillon (which was immediately renamed Ticonderoga by the British and then abandoned) Tiger Roche made his way to New York city. There he met with the Governor and convinced him of his innocence, though he could do nothing against the generally held opinion. His friends back in Ireland sent him enough funds to pay for his passage home, where the warrant for his arrest as accessory to murder had long since expired. From there he headed to London where he was able to borrow enough money to buy himself an officer’s commission, but as soon as the story of the stolen gun emerged he was told he was no longer welcome. The story had been been told by one Captain Campbell, who Tiger tracked down to a coffee house in Charing Cross. He challenged Campbell to a duel, which the pair fought to a draw when both were too grievously injured to continue.

After this Tiger made a stand. He declared publicly that since he could not clear his name in America, instead he would fight any man who repeated the story of his conviction for theft. When Colonel Massey returned from America he was approached in the park by Tiger who asked him to clear his name. Massey refused, and Tiger attacked him. Since Massey had a friend with him the pair disarmed him and then beat him up. Subsequent unsuccessful duels followed, but Tiger never stopped trying to redeem his reputation. Eventually his persistence was rewarded. Corporal Bourke was mortally wounded over in America, and made a death-bed confession that he had stolen the gun, sold it to Tiger Roche, and then lied under oath about it. This didn’t just clear Tiger’s name; it instantly transformed him into a celebrity. He was the innocent man who had never given up, the ferocious tiger who had fought for his honour. Those who had insulted him now fell over themselves to apologise, and Tiger was smart enough to be magnanimous in victory. He returned from London to Dublin with the rank of Lieutenant and the reputation of a hero.

Tiger enjoyed his celebrity in Dublin, attending all the big society parties and attracting a cadre of loyal followers. (The old “murder charge” business was all conveniently forgotten.) He became a local hero when he was walking by Ormond Quay and heard a young woman screaming for help. He ran over and found her, along with her father and brother, being menaced by a gang of ruffians. They had knocked the two men down and were bearing the young lady off when she started screaming. They weren’t counting on Tiger Roche though, who fell in among them with sword and fist flying. He wounded some and put them to flight, rescuing the women and making himself a bona fide Dublin folk hero. After this incident Tiger and some of his fellow officers formed a vigilante group who patrolled the streets at night putting any ne’er-do-wells they met to flight.

While this was going on Boyle Roche was also making a name for himself on the other side of the world, during the Siege of Havana. Spain was allied with France in the conflict and Havana was the main base of the Spanish Navy on the western side of the Atlantic, so it was a natural target for the British to attack and achieve naval control of the seas. The British plan was to put a land army to the south of the city, march north and take the fortress of El Morro (which was positioned to defend the city against naval attack) and use its guns to force the city to surrender. The fortress was well defended and it was a difficult battle, with major casualties on both sides, but after a siege lasting a month the British were able to take the fort and thus the city. Boyle was noted for his bravery in the fighting, and over a decade later when he retired from the army he would receive a knighthood for it.

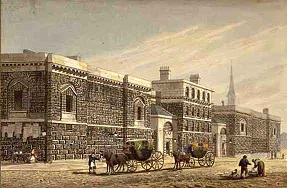

The capture of Havana was one of the final acts of the war, which ended with the treaty of Paris in 1763. Following this peace, the standing size of the British army was greatly reduced. Boyle Roche survived the downsizing of the army, but sinecure positions like Tiger’s were an obvious target for cutbacks. Tiger failed to adjust his lifestyle to take into account the fact that he was no longer earning an officer’s salary, with the result that he fell into debt. He fled Dublin for London, where he continued to build up debts. He tried to get out of debt by marrying a young heiress named Miss Pitt. However he was so extravagant in his courtship that by the time they were married her fortune of £4000 was no longer sufficient to cover Tiger’s debts. He was arrested as a debtor, and the unfortunate couple spent their honeymoon in Newgate Prison.

True to his namesake, Tiger didn’t take imprisonment well. He seems to have suffered some kind of nervous breakdown that made him uncharacteristically meek. On one occasion a fellow prisoner named Buck English attacked him with a stick, and rather than fight back Tiger simply curled up into a ball and literally started crying. However this meek demeanor didn’t extend to his interactions with his wife, who he blamed for his predicament. As a result of his “cruel treatment” she filed for a separation and herself was released from prison. Given the laws of the time it’s unlikely that they were divorced; but their marriage was effectively over.

Tiger himself was released after a few years, possibly due to either a friend who helped him out or a legacy left to him by a relative that covered his debts. The legacy also allowed him to become part of bohemian society again, though his sour disposition earned him few friends. On one notable occasion he was in a billiard hall practicing on a table when someone said that he was keeping other gentlemen from playing. Tiger replied:

“Gentlemen! Why, sir, except you and I, and one or two more, there is not a gentleman in the room.”

A friend later remarked that he was lucky to have gotten away with insulting such a large number of people, and was surprised nobody had challenged him. Tiger said:

“Oh! there was no fear of that. There was not a thief in the room that did not consider himself one of the two or three gentlemen I excepted!”

Tiger became rehabilitated enough in society that he was even considered as a candidate for MP, though not in a seat that his party would win. (He was intended merely to make life difficult for the other candidate, something he would have excelled at.) However he was “bought off” by the candidate and refused to stand. By now some of his old spirit had returned, as evidenced when two men tried to mug him as he returned to his apartments in Chelsea. Though both had pistols and he only had a sword Tiger still managed to drive one off and capture the other. When the two men stood trial it was Tiger’s intercession on their behalf that saw their sentence reduced from hanging to transportation. As if to balance out this good deed though, around the same time he persuaded a widow and her daughter to let him manage their funds. Through a combination of embezzlement and incompetence he squandered their entire fortune.

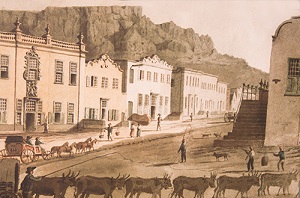

After this escapade he seems to have decided it would be a good idea to leave London for a while, so he signed up as a captain for the East India company’s private army and boarded a ship to his posting. [2] On board the ship he managed to alienate every other passenger, and when the ship docked at Madeira he was challenged to a duel by one of them named Captain Ferguson. Tiger refused the duel and apologised, an act of cowardice that led to the passengers getting the captain of the ship to expel him from the officers’ table. He was forced to eat with the sailors and the common soldiers, something which grated on him sorely. He made several threats against Captain Ferguson, something which came back to haunt him the next time they docked in South Africa. Because on the night that the ship docked there and the passengers all stayed ashore, somebody stabbed Captain Ferguson nine times and killed him.

Tiger Roche was an immediate suspect, both due to the argument and to his having been seen hanging around Ferguson’s lodgings on the night of the murder. He fled into the jungle but was captured and put on trial by the local Dutch authorities. Amazingly they acquitted him and he headed on to India, but the ship he had originally been held on had arrived before him and given news of the murder. He was arrested again and charged with murder for a second time. He tried to argue that he had already been tried and that the crime had not been committed on British soil, but it was in vain. He was sent back to England in chains to stand trial.

The trial of David “Tiger” Roche for murder began in the Old Bailey on the 8th December 1775. He was charged with murder, and his defense was once again that he had been tried and found innocent by the Dutch court. This led to a legal quagmire as the court was not qualified to decide the issue of international law involved, so after a few days Tiger agreed to change his plea to a normal one of “Not Guilty”. The main witness against him was the ship’s surgeon, who said that he had been eating dinner with Ferguson when a message was brought and Ferguson left. Following that he heard a report of people fighting outside, and when he went out he passed Tiger sheathing his sword and went on to find Ferguson slumped against a wall dying from his wounds. The main witness for the defense was a sailor called Goodwin, who testified that he had seen the altercation and that Ferguson had struck Tiger with a cane and had been the first to draw his sword. It was on Goodwin’s evidence that Tiger had been acquitted in Madeira, and it was enough to acquit him once again.

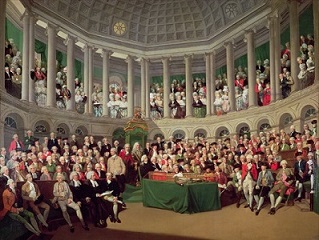

What happened to Tiger after his trial is unclear. The same year Boyle Roche had retired from the army and been elected as an MP for Tralee to the Irish Parliament. [3] His brother’s trial for murder must have been a major scandal for him, and one that he could ill-afford. The most common supposition then is that Tiger was offered money by Boyle if he would move out to India and settle there. If he did, then he never returned as there is simply no record of him after the trial. The elder Roche brother, the blot on the family honour, simply vanishes from the pages of history after this point. Boyle Roche, though, was only now beginning to establish his fame. When war broke out against the “ungrateful colonials” in 1776 he took up his major’s commission once again as a volunteer, though his service to his country came in the form of recruitment drives. One notable speech that he gave in Limerick caused 500 men to volunteer, earning him a bonus of 250 guineas from a grateful local aristocrat. It included the following florid passage:

A more critical period never presented itself, nor had we ever a fairer opportunity of shewing our attachment to the illustrious house of Hanover, than the present, as his Majesty’s deluded subjects in America are in open rebellion, and like unnatural children, wound their ever indulgent parent, forgetting the torrents of blood spilt, and heap of treasure expended for their preservation. His Sacred Majesty now calls and our fidelity obliges us, and I hope your instinct prompts you, to obey the dictates of so grand a master. Let us then, my brave and loyal countrymen, join hearts and hands and cheerfully step forth in the glorious cause of our Creator, our King and our Country.

Boyle Roche married Mary Frankland, the daughter of an English admiral, in 1778. They never had children but unlike Tiger it seems that Boyle and Mary had a happy and lasting marriage. This stable home life helped Boyle to keep his feet on the ground during his political career. Boyle as a political animal was a strange beast. He was a Tory and was very pro-government, enough so to earn him a knighthood in 1782. (Ostensibly this was for his “bravery in the capture of Havana” twenty years earlier.) What he became most famous for were his extremely quotable lines, many of which are still being written about to this day. A few of the highlights:

“It would surely be better … to give up not only a part, but, if necessary, even the whole, of our constitution, to preserve the remainder!”

[The French Revolution] “would cut us to mincemeat, and throw our bleeding heads on that table to stare us in the face.”

“The cup of Ireland’s misery has been overflowing for centuries and is not yet half full.”

“We should silence anyone who opposes the right to freedom of speech.”

“Why we should put ourselves out of our way to do anything for posterity, for what has posterity ever done for us?”

“It is impossible I could have been in two places at once, unless I were a bird.”

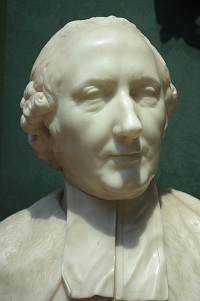

The latter gives us a bit of a clue to Boyle’s real character. Foolish on the surface, it’s actually an allusion to a play called The Devil of A Wife by Thomas Jevon. Similarly while Boyle is often derided as an idiot by later writers due to his foolish quotes, there was a shrewd operator lurking beneath the surface. This became evident in 1783 when he was the key player in thwarting a bid by the Bishop of Derry, Frederick Hervey, [4] to extend the right to vote to Roman Catholics. Obviously the government was horrified by that idea and decided to sabotage it. So the secretary of state, George Ogle, gave out a false statement on the Bishop’s behalf that he had no plan to seek the franchise on behalf of the Catholics. Boyle backed this up, saying that he was there when the statement was given. By the time the Bishop arrived in Dublin to deny the statement the damage was done, and public opinion had swung behind a version of the Reform Bill that did not include the right to vote. And, due to his foolish reputation, no blame attached to Boyle for the affair.

Boyle Roche may have had a reputation as a bit of a foolish type, but he was no pushover. On one occasion the Opposition tried to “cough out” a speech he was giving. Boyle paused, reached into his pocket and produced a handful of “wonderful pills to cure a cough”. They were bullets, and the implication (and implied challenge to a duel) was clear. Nobody was prepared to challenge the old veteran, and he finished his speech uninterrupted. At least it was his own speech on that occasion. The MP for Augher, Edmond Stanley, was once shocked to hear Boyle deliver perfectly the exact speech that Stanley himself planned to give. He had left his manuscript behind in the coffee room, and Boyle had picked it up and memorised it in one reading. Afterwards he gave the speech back to Stanley, thanking him for “the loan” of it.

Boyle career as an MP came to an end in 1800, largely thanks to his own campaigning for it to do so. That was the year that the “Acts of Union” were passed, merging the Kingdom of Ireland and the Kingdom of Britain into a single kingdom. (Previously they had been in a “personal union”; which is to say that they were separate kingdoms that happened to have the same king and rules of succession.) The Union was in large part due to the rebellion in 1798 and the brutal reaction to it. Loyalists hoped that it would counter any possibility of Catholics getting full voting rights, while those who had previously opposed a Union hoped that it would take the reins of power out of the hands of the “Protestant Ascendancy”. A healthy set of handouts to the former critics of the act (in the form of titles and honours) secured a solid majority for the bill. The debate over the bill led to another of Boyle’s classic quotes:

There is no Levitical decree between nations, and on this occasion I can see neither sin nor shame in marrying our own sister.

Boyle could easily have stood for a seat in the British parliament, but at the age of 64 he decided that he was ready to retire. With a cushy government job that had no work attached but which doubled his pension, of course. He spent the next seven years living in quiet and comfortable obscurity in Dublin before he died in 1807 at the age of 71.

Boyle Roche’s respectable life stands in sharp contrast to the brutal ignominy of Tiger Roche’s biography. As such, it may seem that nature wins out over nurture in this story. However, chance also seems to have played a role. If Tiger had accepted the offer of a commission and had entered the army in his youth as his brother did, might he have led as staid a life? On Boyle’s side, given the ruthlessness he sometimes showed in his political career might he have been as wild as Tiger if the situation had demanded it? The truth is that it’s impossible to say. They were two different men who lived two different lives, linked only by the accident of birth and a handful of shared DNA. Both became nothing more than a footnote in the other’s biography, two lives too different for history to ever reconcile.

Images via wikimedia except where stated.

[1] It’s been written that these ruffians were members of the “Pinkindindies”, a gang of upper class student ruffians (often associated with the Hellfire Club) who ran rampage on Dublin throughout the 1770s. However this incident occurred about ten years too early for it to be them. Their name came from their habit of using swords with the tips broken off to reduce the risk of them accidentally killing someone, but they were perfectly happy to stab people with those broken ends in the pursuit of their goals. The leader of the Pinkindindies was Richard Crosbie, who is better known for being the first Irishman to make a flight in a hot air balloon. The commemorative statue of him in Ranelagh Park makes no mention of his two convictions for assaulting prostitutes.

[2] Tiger’s trial record at the Old Bailey for the incident on the voyage makes mention that he was traveling with “Mrs Roche”. Who this actually was is unclear; it seems unlikely that it was the former Miss Pitt as they were separated, but by that note he would also have been unable to remarry unless she had died. It’s possible that this was some paramour traveling as his wife. This would be backed up by no other source outside of the trial record mentioning her, perhaps out of delicacy.

[3] This was pre-Act of Union, so Ireland still had Home Rule.

[4] Younger brother of the notorious Casanova figure Augustus Hervey