Sayyida al-Hurra, Muslim Pirate Queen

Piracy has been used throughout history as a tool of state policy. Giving free reign to brigands to attack civilian merchants from an enemy kingdom is definitely one way to weaken your enemy and enrich yourself, though one that does seem morally reprehensible to modern sensibilities. At the time, it was common for people to in one breath denounce the attacks on their own shipping by vicious pirates and in the next laud the successes of their own brave privateers. Among those most denounced were the “Barbary Pirates”, a catch-all term used by the Christian kingdoms of Europe to refer to the Muslim pirates who ravaged Mediterranean shipping for over three hundred years. But to the first of those pirates, they were merely taking their revenge for what had been done to them by those kingdoms. None expressed this attitude like the pirate queen of Morocco, Sayyida al-Hurra.

She wasn’t called Sayyida al-Hurra when she was born, because that’s not a name at all. Sayyida is the female form of Sayyid, which means “lord”. Similarly al-Hurra (meaning “the honored”) was the title traditionally given at the time to a woman who held a position of independent power but who was not a ruler. This combination of titles is what she is referred to throughout the histories, with her actual name being left out. (It might have been Aisha; but we can’t be sure.) Partly this is because Christian writers did not realise this was just a name, but it does also seem to be a deliberate choice. Who she had been born as didn’t matter. It was who she made herself that was important.

She was born in 1485 in Andalusia in southern Spain. Her father was Moulay Ali ibn Rashid al-Alami, a Muslim noble who could claim direct descent from the Prophet Muhammad himself. His wife (and Sayyida’s putative mother) was a Christian-born Spaniard who had converted to Islam named Zohra, whose maiden name was Fernandez. When Sayyida was seven years old, her family were forced to flee Andalusia as the grand “reconquista” of Isabella and Ferdinand swept in to drive the Muslims from the Spanish peninsula. For the rest of her life, Sayyida would bear a grudge against the people who had driven her family from her childhood home.

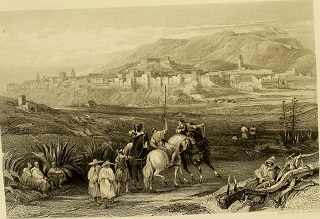

The family settled in Chefchaouen, a site a few miles inland from the Moroccan coast which Sayyida’s father had founded originally as a military base in 1471. Many refugees fleeing from Spain settled there, transforming it into a city that would become known as “the blue pearl” for the distinctive shade they painted the walls. This was where she spent the remainder of her childhood, receiving the education that the daughter of a nobleman merited. She learned languages, theology, mathematics, and other disciplines. Among her tutors was Abdallah al-Ghazwani, a famed religious scholar and architect who is nowadays honored in Sufism as one of the “seven saints of Marrakesh”.

Some time after the turn of the century Sayyida married Abu Hassan al-Mandari, a nobleman thirty years her senior. Some sources say she married him in 1501 (at the age of 16), others that she married him nine years later in 1510. (She might not even have married Abu Hassan himself but rather his son, though this is unlikely.) He was the head of another of the noble families that had fled Spain, and this was a diplomatic marriage which had been arranged many years earlier. However it does seem to have evolved beyond that into genuine affection and partnership, as the pair worked to improve the city of Tétouan.

Like Chefchaouen, Tétouan was a fortress that had been transformed into a true city by refugees from the Reconquista. It had been destroyed by the Christian kingdom of Castile around 1400 because it had become a base for Muslim privateers to attack their shipping. In 1484 the Wattasid sultan Muhammad ibn Yahya had granted the site to Abu Hassan after he had fled Spain. He had raised fortifications around it to prevent Spanish attack, and within the walls houses had sprouted up. A Grand Mosque was built, and Tétouan was transformed from a fortress into a bustling city, humming with trade. The “Old City” of Tétouan is nowadays a UNESCO World Heritage Site, preserving the buildings that Sayyida and Abu Hassan had built.

Sayyida learned a lot from her husband, who treated her as an equal and as more of a co-governor than as a subordinate. When he died in 1515, she was the one who assumed the reins of power in her own right. This was when she took the title of “Sayyida al-Hurra, Hakimit Titwan”; literally “the honourable great lady, governor of Tétouan”. It was unusual for a woman to rule in Islamic society at that time, but far from unknown. Competency was the key to leadership, and as long as she was able to do the job that was enough for them. (Though it probably helped that her brother was a vizier to the sultan of Fez, Ahmed al-Wattasi.) And as she would show, she was more than up to the task.

Sayyida had never forgotten how her family had been driven from their home by Isabella and Ferdinand, and she was determined to pay their kingdom back for that affront. And if she could make some money and enrich her city at the same time, that would be all to the good. Tétouan had been a base for piracy before, why not make it one again? With this plan in mind, Sayyida sent envoys west in order to arrange a meeting with the king of the Mediterranean pirates, Oruç Reis.

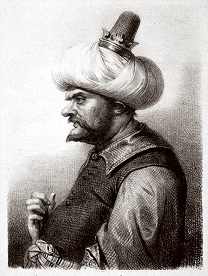

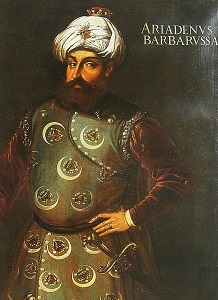

Oruç Reis was a sailor from the island of Lesbos, the son of a Turk and a Greek. He was initially a legitimate merchant, but his brother was killed and he was captured in a sea-raid by the Knights Hospitaller. When he was rescued by another of his brothers he turned privateer to seek revenge. The Reis brothers became state-sponsored corsairs, getting funding and patronage for their fleets from Muslim rulers in exchange for confining their ravages to enemies of the state; and for kicking back a third of their spoils of course. Oruç Reis made his base on the island of Djerba (off the coast of modern-day Tunisia) where he made a specialty of raiding boats belonging to the Papal States.

Sayyida and her people would already have had reason to be well-disposed to Oruç Reis, as he had put his fleet to work ferrying refugees from Spain to Africa between 1504 and 1510 as the persecution of religious minorities on the Iberian peninsula intensified. This act of charity earned him the affectionate nickname of “Baba Oruç” – “Father Oruç”. It’s thought that it might be a misinterpretation of this which led to the name he was known by in the west: “Barbarossa”. (Which is the Italian for “Red Beard”; whether Oruç Reis actually had a red beard isn’t certain.) His other nickname of “Gümü? Kol” was earned in 1512; it means “Silver Arm” and that is what he had as a replacement after he lost the original in a battle to drive out Spanish colonists from Africa.

With an agreement from Oruç Reis that she would control the western half of the sea while he held the east, Sayyida launched into her pirate career in earnest. Because of her position it was Portuguese traders in particular who bore the brunt of her raids, and she soon became deeply hated by them. The Portuguese “prayed for God to allow them to see her hanged from a ship’s mast,” according to Spanish historian Germán Vázsquez Chamorro. This would have been unlikely as she never actually sailed out or led any of these pirate raids herself. She was content to manage things from behind the scenes, and to negotiate the ransoms for the many Portuguese and Spanish sailors her men captured. One notable prize was the wife of a Portuguese governor, for whom she received a hefty payment. Small wonder that the Portuguese envoy to the court of Fez, who was the point man for many of these negotiations, derided her as “a very aggressive and bad-tempered woman about everything.”

The ambitious Oruç Reis wanted a kingdom of his own, and so he and his brothers set out to drive the Spaniards from Algiers and reclaim it. Once they did so Oruç Reis deposed the previous ruler and declared himself Sultan, but he was soon forced to recognise reality and offer to join the Ottoman Empire in order to secure their protection. With their aid the Reis brothers were able to hold Algiers, but Oruç was killed during the fighting. His brother Hizir took up his leadership position and was also known to Westerners as Barbarossa. To his fellows he was known as Hayreddin, which means “goodness”, a title bestowed on him by an Ottoman sultan. The Reis brothers had hitched themselves to a rising star in their choice to ally with the Ottomans as that sultan was Suleiman the Magnificent, who would transform the Ottomans into a Great Power of Europe. Hayreddin served Suleiman loyally both as Pasha of Algiers and as the admiral of his Mediterranean fleet.

Sayyida continued her alliance with Hayreddin, and her fleet kept on working the western Mediterranean. When the Ottomans and the French became allies it further isolated the Iberian countries, which suited Sayyida just fine. She continued to ravage their fleets over the following decades, which all eventually culminated in the peak of her career as a pirate: the raid on Gibraltar in 1540. At the time the Rock was a possession of Charles V, the Holy Roman Emperor. He was a long-time rival of the Ottomans and had even tried to lure Hayreddin away from them with an offer to make him “lord of North Africa”. The messenger had been told to arrange Hayreddin’s assassination if the offer was rejected; he never had the chance as the insulted Pasha killed him in response to the offer. The chance to bloody the Emperor’s nose was one that Hayreddin was willing to support; and a joint expedition was planned.

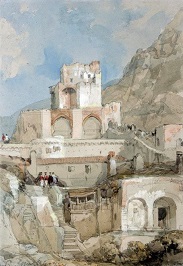

Gibraltar was a soft target, all the softer for not realising it was one. Fortifications had been allowed to crumble, despite the enormous strategic importance of the island to the Empire. It was where their fleet found harbour for maintenance and repair; with most of the work being carried out by enslaved Turkish prisoners. These prisoners were not well guarded, and several of them managed to escape. In 1540 there was a mass breakout led by man recorded as being called Caramani. This is an Italian surname, so either he was a convert or it’s a transliteration of a Turkish name. The escapees found refuge in Algiers, where they met with Hayreddin’s lieutenant Hasim Aga. Caramani and his men had vital information for planning the raid, including the issues with the fortifications, unguarded approaches and where the troops were stationed throughout the island. As a result Caramani was put in charge of the raid on the island, with the fleet led by an experienced Ottoman admiral.

The fleet (which included a number of Sayyida’s ships) was spotted as it made its way to the island in September of 1540, and Gibraltar immediately started scrambling to prepare for a possible attack. As the attackers knew, this wasn’t something they could really do in the time available to them. The fleet landed on the east side of the island on the 9th of September, and sent one of their number who could pass as a Spaniard out to spy on the island. He went to a nearby town and bought some bread and fish, satisfying himself as he did so that the fleet had not been spotted. So they sailed south towards the main harbour. On the way they were challenged by some guards, but they lied and said they were Spanish galleys, part of a fleet coming to the island. As a result they were able to make a landing and begin an assault on the town.

How successful the raid was is a matter of debate. According to the western sources (which are the most detailed) it was a great victory in driving off the invaders, with each setback they suffered hailed as a sign of divine favour. On the other hand they can’t avoid admitting that the Turks managed to free a large number of slaves, and conversely also managed to capture a large number of locals and make them slaves of the Ottomans. They didn’t manage to capture and hold the island, but it’s doubtful they ever intended to. Reading between the lines of the local accounts it looks like a classic raid, with the invaders withdrawing to their ships in good order once they’d spent as much effort as they intended on securing booty. In the end the Turks suffered less than twenty casualties and captured at least seventy locals, plus fifteen crewmen from two unfortunate merchant vessels that arrived into the harbour during the raid and were immediately captured.

While a negotiation under truce was being made to ransom the prisoners the Turkish camp was attacked by two brothers named Anton and Francisco Calvo, a violation of diplomatic norms that nonetheless became one of the small victories that the western chroniclers seized on after they managed to rescue some of the prisoners. The rest were loaded onto the boats and taken off to the fortress of Velez de la Gomera, where those who were worth more as ransom than slaves were sold off to the local lord. He then ransomed them back to Gibraltar for the 5000 ducats he had paid for them; plus a 10% commission of course. Some of the Spanish historians claim that the Turkish fleet was then attacked by the Spanish armada on their way back to Algiers and fourteen of the sixteen ships were sunk, however it seems like this may be a conflation with a later raid on the island of Alboran that ended poorly.

By this time Sayyida’s control over the “Barbary pirates” in the western Mediterranean made her a power to be reckoned with in the Muslim kingdoms of northern Africa. In fact she was powerful enough that when the Watassid Sultan of Morocco proposed a marriage alliance to her, she was able to dictate her own terms for the arrangement. Sultan Ahmad el Outassi was persuaded to hold the wedding ceremony in Tétouan; an unprecedented display of deference from the ruler of a kingdom to the ruler of a city-state. The marriage appears to have been solely a diplomatic one, as the two continued to live in their separate capitals after that. This did make Sayyida literally a pirate queen.

Sayyida al-Hurra reigned as governor of Tétouan for over thirty years, but in 1542 that rule finally came to an end. Open war with Portugal destabilized trade in the city and setting the stage for her overthrow. Taking advantage of this Ahmed al-Hassan al-Mandari, a kinsman of Sayyida’s first husband and the husband of her daughter, reached out to the enemies of her new husband. The Wattasids were on the wane, and the Saadis were on the rise. They were a noble family from the southern part of Morocco who grew powerful enough that the Sultan tried to attack and humble them, a move which backfired when they held him off and forced him to recognise their independence. The war with Portugal offered them a chance to position themselves as the saviours of the kingdom and set them on the path that would see them take over the kingdom within fifteen years. With their support Ahmed forced Sayyida to abdicate, and she retired to her childhood home of Chefchaouen. She lived there for around another twenty years, and died in 1561.

Sayyida may have fallen from power, but the echoes of her rule continued to be felt for some time. The people of Tétouan kept up their piratical pursuits, until a retaliatory raid by the Portuguese destroyed their harbour in 1565. Mediterranean piracy would remain a serious problem right up until the 19th century. In fact it was pirates operating out of northern Africa that led to the initial formation of the US Navy in order to protect their merchant vessels. As for Sayyida’s personal impact; she was the last recorded woman to bear the title of “al Hurra”. The egalitarian attitudes that had prevailed during the times of Muslim Iberia that had given freedom to people like Wallada Bint al-Mustakfi that they could not have enjoyed in any other kingdom were now fading away. But the memory of Sayyida al-Hurra, the pirate queen of Morocco, remained.