Redmond O’Hanlon, Irish Outlaw

When you look at the witch-trial fever that swept over Europe in the 17th century, it’s noticeable how it largely left Ireland untouched. This wasn’t really because of greater tolerance on the part of the Irish people, but rather reflects the fact that they didn’t trust the authorities enough to denounce their neighbours to them. They were a people under occupation, with rulers imposed upon them from England who they knew had no love for them. It’s not surprising then that, like many such oppressed people, they turned to alternative authority figures to protect them. One such person was the man they called “the Count”, Redmond O’Hanlon.

Redmond O’Hanlon was probably born in Poyntzpass in County Armagh, some time around 1640. This was a place and time where strict record-keeping was not a priority, a lawless corner of the land that King James of England and Scotland claimed for his territory. Popular local tradition has it that he was actually born 15 miles from the town, at the foot of Slieve Gullion. This might be a part of his myth though, linking him to the hero Cu Chulainn who was also born on the mountain. (In fact the mountain and Cu Chulainn both get their name from the same place, the legendary smith Culann.)

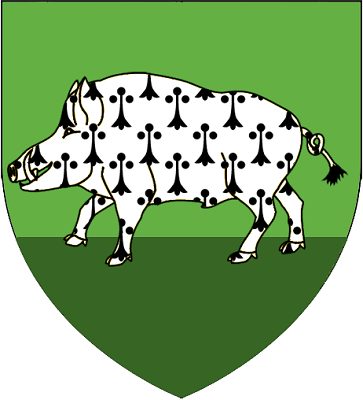

Redmond’s father was Loughlin O’Hanlon, who would have been heir to the chiefdom of the O’Hanlon clan if the times had been better. In 1599 Sir Eochaidh O’Hanlon had ruled all the land from Newry to Armagh, but his son made the mistake of siding with Sir Cahir O’Dochertaigh in a doomed rebellion. Eochaidh Og was exiled to Sweden, while most of the O’Hanlon lands were confiscated and given to Scottish and English planters. In 1611 they were driven from their castle at Tandragee and it was taken by an English lord, Oliver St John. This was why Redmond was later described as the “rightful heir of Tandragee”.

They did manage to hang on to some of their land though, with about a quarter of it being granted back to O’Hanlon family members as planters. This probably means that they had converted to Protestantism, as does the fact that young Redmond was given a high quality education at “an English school”. He did extremely well there, showing a talent for languages that would serve him well later in life. He also learned etiquette well enough, according to some accounts, to be accepted into the service of Sir George Acheson. Sir George was baronet of Glencairny in Nova Scotia, a title which his father had bought by helping to pay for the British settlement of the area. He was also the High Sheriff of Tyrone and Armagh, so his service offered a good opportunity for Redmond to do well. Unfortunately he got into legal trouble (stealing horses or murdering a man in a quarrel, depending on who you believe) and was forced to flee to France as a teenager.

At least, that’s one version of events. Another still has Redmond fleeing to France for committing a crime but says that he was never in service to Sir George Acheson. Another has Redmond born 20 years earlier and fighting in the 1641 rebellion and then in the Irish Confederation (which was allied with the Cavaliers against Parliament). In this version he fled to France after the Confederation was defeated in 1652 and, like many Irishmen who fled that conflict, joined the French army. This might be conflating him with a different O’Hanlon however. In the end, though one version might be considered more likely than the other, given that the earliest source we have is from 1682 it’s hard to say for sure how Redmond O’Hanlon wound up on the run in France.

It’s equally hard to say exactly when he came back to Ireland. One version (which lines up with him being older and a war veteran) says that he came back in 1660 when Charles II retook the throne, hoping to reclaim his family lands. If that’s the case he was disappointed. The English king might have restored the lands of his own people who had fought against Parliament, but the Irish were given no such courtesy. Alternatively he might have come back several years later, towards the end of the 1660s. Either way he made his way back to Armagh, and found a country left devastated and lawless by years of war.

Over the next few years Redmond essentially installed himself as clan chief over the old O’Hanlon territories, styling himself “the Cunt” despite having no legal title to the lands. He taxed his subjects, and protected those who paid their taxes. On the other hand, those who did not pay their “taxes” were fair game for his men to rob. Despite the authorities in 1674 denouncing him as an outlaw and putting a price on his head, the fact is that for whatever reason he was considered as the legitimate ruler of the territory by priests, landlords and even officers of the local militia. All of these supported him (though surreptitiously) with information.

Or he was just a rapparee, a common outlaw who ran a protection racket well ahead of its time. The behaviour of those who roamed around Ireland hunting outlaws was practically guaranteed to drive the local people into sympathy with the outlaws and lead to them being painted as heroes even if they weren’t. With a sizeable bounty being placed on Tories (outlaws), these men were incentivised to do what it took to find their prey. These were the spiritual descendants of Sir Humphrey Gilbert, the knight who a hundred years before had wiped out villages of women and children to suppress Irish guerrillas and decorated his campsite with their severed heads. The Tory-hunters were similarly vicious in their hunting of bandits, but thought they caught more than a few they never caught Redmond O’Hanlon.

That’s not to say they didn’t come close though. One of the most infamous Tory-hunting families were the Johnstons of the Fews. (The Fews being a barony roughly around Newry, on the modern border of Northern Ireland.) There’s a story that they hunted Redmond to the shore of Carlingford Lough, and he was forced to swim for safety. This story may well be apocryphal though, since the Johnstons are best known for the activitieso of John Johnston (sheriff of the Fews) forty years later. It might have been a comforting legend to the locals to imagine that Redmond O’Hanlon could have been capable of escaping “Johnston of the Fews”.

Someone who definitely was an enemy to Redmond was the man who was supposed to be lord over the territory Redmond claimed: Henry St John. He was the youngest son of John St John, a prominent Royalist Cavalier whose family lost several members during the civil war. It was probably in recognition of this service that he was granted the old O’Hanlon lands after the Restoration. He made his home in Tandragee, on the site of the old O’Hanlon home, something which would have made him an enemy of Redmond regardless. But his hardline stance against “the Count” meant that the two men were on a collision course that would have fatal consequences.

The first major casualty of their war was Henry St John’s only son (whose name has not been recorded). The young man was leading an expedition to hunt Redmond when he fell ill. (The illness was recorded as “a chill”, which was probably pneumonia caused by damp conditions.) He died, aged only 19. Henry was devastated by the death of his son, and chose to blame Redmond for it. After all, if it weren’t for the outlaws his son would never have been out there to catch that chill, would he?

Henry St John turned to a scorched earth policy to try to isolate Redmond, with the aid of a troop of soldiers dispatched from Dublin. By now Redmond was being described as being “pre-eminent among all the tories in Ulster”. These men persecuted Redmond’s family, resulting in most people with the surname “O’Hanlon” fleeing west from Armagh to Donegal. (It’s definite that some of his relatives settled in Letterkenny.) The soldiers burned down woods that were being used as hideouts, forced people colluding with Redmond to emigrate to America, and generally took advantage of the local population so much that Oliver Plunkett, the Archbishop of Armagh, mentioned in a letter to the Pope that the soldiers were far worse than any outlaws.

In autumn 1679 Henry St John was out riding with the Reverend Lawrence Power, an Anglican vicar who was responsible for the parish of Tandragee. Suddenly they were attacked by a group of bandits, who took the landlord prisoner and warned the priest that if anyone tried to rescue him they would kill him. The Reverend Power didn’t have time to pass on that warning though, as a passing group of Planter tenants saw what was happening and rode in to rescue their landlord. Lead started flying, and it was disputed as to whether the outlaws made good on their threat or whether a tenant bullet went awry. What nobody could argue with was the conclusion. Henry St John lay dead on the ground of Drumlin Hill, with a bullet in his brain.

Though it wasn’t even clear if the outlaws had any connection to Redmond O’Hanlon, the Reverend Power didn’t let that stop him. He took to the pulpit to denounce both the outlaws and anyone who worked with them, dealing a substantial blow to Redmond’s popularity. He wasn’t the only priest who condemned the bandits, either. Father Edmund Murphy, a Catholic priest, also spoke out against “the Count” for stirring up trouble and giving the English an excuse to persecute the locals. Redmond tried to stop this by forbidding his “subjects” from attending Father Murphy’s sermons, on pain of having their cattle stolen or even being killed. This forced Father Murphy to abandon his flock and get another priest to take over.

Father Murphy was not happy about this, and decided to try to lure Redmond into an ambush where he could be attacked and killed. He recruited a disgruntled former member of the O’Hanlon gang, a man named Cormac Raver O’Murphy who had taken to robbing the merchants who had purchased the Count’s protection. They came up with a plan, and contacted the local army garrison to let them know. However they found out that Lieutenant Henry Baker, the commander of the garrison, was being paid off by Redmond and had no interest in helping them.

This type of corruption and cooperation was exactly what the Reverend Power was preaching against, and his sermon at St John’s funeral had denounced those present who had taken money from the outlaws. He had gone further into sectarianism though, insisting that the Protestants should prove their right to rule the land by destroying the Tories and putting the natives in their place. That made his narrative of conspiracy feed right into an ongoing situation in England – the Titus Oates plot.

That particular bundle of prejudice and public hysteria instersected with Redmond O’Hanlon directly when it claimed its final victim; the Catholic Archbishop Oliver Plunkett. Plunkett was a known opponent of the outlaws and it was actually at his instruction that Father Murphy had preached against O’Hanlon. His prosecution on obviously trumped-up charges of conspiring to kill the king still provoked outrage among those who considered him an honorable opponent. And outrage turned to fury when they found out that Father Murphy was one of those lining up to testify against him.

By that point the persecution had already led to the death of twenty one priests (nine executed, twelve died in prison) but after the execution of the Viscount Stafford it was beginning to run out of steam. Still, the cabal of powerful Protestant lords behind it were determined to end on a high note with a convincing conviction of Plunkett. They even reached out to Redmond O’Hanlon, offering him a full pardon if he testified that Plunkett had colluded with the outlaws. Though Redmond was trying to get a pardon at the time, he refused to compromise that far.

Unsurprisingly Father Murphy agreeing to testify against Plunkett made it hazardous to his health to stay in Armagh, so he moved to Dublin. It wasn’t Redmond who was after him though, but rather Lieutenant Baker and his second in command Ensign John Smith. They might have been worried that Father Murphy would reveal their connection to Redmond to the authorities. When he took refuge in Dublin Castle they sent him a rather definite message: the head of one of the men who had been helping to set up Redmond turned up as that of an “outlaw” sent in to claim the bounty. To his horror the bounty was paid, illustrating to the priest just how vulnerable the lives of all those he might have cared about were to these authority figures.

But though Redmond had managed to take over the local law enforcement, he had become an embarrassment on a national scale. He knew that he couldn’t keep ahead of the authorities for long, which was why he was trying to secure himself a pardon. Unfortunately James Butler, the Lord Lieutenant of Ireland (and Duke of Ormonde) was already facing some backlash for his refusal to take the harsh measures against Catholics that the hardliners in London were pushing. He couldn’t afford to look soft on the outlaws, and so he began searching for a way to take care of the Redmond O’Hanlon problem permanently.

Butler’s agents found the perfect person to carry out his plan to take Redmond down. William Lucas of County Down was an ex-military man who had a good reputation from his time in the army and was known for not being very sympathetic to the “peasants” on his land. What made him perfect for the job was that his family had a history of cooperation with the O’Hanlon gang, giving him valuable contacts. So he was approached secretly and offered £200 for the head of Redmond O’Hanlon. To help in the effort, he was given the authority to take command of any troops he needed and to recruit any outlaw not guilty of murder as an agent in exchange for a pardon.

Two people who later claimed to have been recruited by William were his uncle Sir Toby Poyntz (a local justice of the peace who had been accused of collaborating with Redmond) and Sir Toby’s son Charles. (This might have been them retroactively trying to take some credit.) Whether through Sir Toby or on his own, William managed to recruit someone right in the Count’s inner circle: Art McCall O’Hanlon, Redmond’s foster brother. Art was one of the few people Redmond trusted, and in exchange for a pardon he agreed to betray that trust.

On the night of the 25th April 1681 Art O’Hanlon, Redmond O’Hanlon and another outlaw named Willie O’Shiels were camping out in the hills above Eight Mile Bridge in County Down. Their plan was to ambush farmers returning from the market at Hilltown with the money they’d earned selling their produce. According to Art, he and Redmond got into an argument that ended with Redmond telling him that he was expelled from the gang. Art responded by shooting him in the chest. According to other reports, Art shot Redmond as he slept while Art was supposed to be on watch. Either way the Count was dead, assassinated by the coward Art McCall O’Hanlon.

Art immediately headed to Eight Mile Bridge to fetch one of the soldiers on guard there, but by the time they returned to retrieve the body Willie O’Shiels had already cut off Redmond’s head and fled. His objective was apparently to prevent them being able to prove that they had killed his chief. Willie was right to guess that they would want that head badly, enough that William Lucas had a proclamation issued offering him a pardon if he gave the head to the authorities. Willie accepted the offer. The head was put on display at Downpatrick prison, where Redmond’s mother came to see it. Traditionally she is supposed to have created a “keen” (a traditional Irish lament for the dead) which translated as:

Dear head of my darling,

How gory and pale;

These aged eyes see thee,

High spiked on their jail.

That cheek in the summer,

No more will grow warm;

Nor that eye e’er catch light,

But the flash of the storm.

After Redmond’s death, the persecution of the O’Hanlons and of outlaws in general took a turn for the more severe. Without him paying off the authorities, “Tory-hunting” became a more attractive prospect. William Lucas in particular became well-known for persecuting the native population, and employed both Art O’Hanlon and Willie O’Shiels to help him do it. He became so bloodthirsty that a captain stationed at Tandragee wrote to the Lord Lieutenant telling him that they were executing innocent people as outlaws, seizing lands for themselves and were likely to provoke a rebellion if not reined in.

This persecution resulted in Redmond’s surviving family fleeing northwest, to Donegal. Redmond was originally buried at Ballynabeck, near Tandragee, but according to local stories his son (also named Redmond) exhumed the body and took it to Letterkenny. There it was buried in the O’Hanlon family tomb in the graveyard outside the Church of Ireland church for Conwal Parish.

Though local stories glorifying Redmond O’Hanlon persisted, he never attained the folk hero status that similar outlaws and rebels received. In part, this was due to the changing nature of the area; the local population of Armagh and Down rapidly shifted towards Protestant planter families after the natives fled west. And in part it was due to the poor documentation of his life; Sir William Scott considered writing a novel about him (which would have made him famous) but gave up when research proved too difficult. So he remained the province of local writers and singers, who kept his memory alive but failed to spread it far beyond the lands that the O’Hanlons had once claimed. So he stayed a local legend; perhaps a more fitting fate for one who seems to have been content in life to rule over his territory.

Images via wikimedia except where stated.

This is the last Terrible Person from History for the foreseeable future. I’d like to thank everyone who’s followed along these last five years; if you had at least half as much fun reading it as I did writing it then I’d be happy.