James MacPherson, Scottish Poet and Translator (or Fraud)

There’s a thin line between lying and creating, sometimes. Is the forger who creates new paintings in the style of the old masters any less of an artist than they were? His work is skillful, his subjects original, though he may match their style. Does that make him any less of an artist than the many illustrators and other creators who follow a “house style” to produce their work for hire? A similar, though more ambiguous, paradox applies to James MacPherson. Either he was a gifted translator who took works of ancient genius and recast them in the modern tongue to bring wonder to the world. Or he was a liar and a fraudster – and himself the genius who created those very works. To this day, we don’t know which.

James MacPherson was born in 1736 as the son of a farmer in the Highlands of Scotland. His father was related to the chief of the MacPherson clan, which lent him some status in the area. He grew up in tumultuous times, as the Jacobite Rebellion broke out in Scotland when he was nine years old. This was an attempt by Charles Edward Stuart to regain the throne of Britain that his grandfather King James had lost to King William of Orange over fifty years earlier. As the Stuarts were a Scottish house, Charles began his campaign in Scotland. Ruthven, where young James MacPherson grew up, was a barracks town for the surrounding lands and so he witnessed soldiers marching out to fight for Bonnie Prince Charlie; and then the English soldiers riding in and burning the barracks to the ground. In the end the rebellion ended with Charles thoroughly defeated, and with the Scottish Nationalist movement which had backed him crushed. The Scottish clan system was outlawed, while London began a long campaign to make the Scots identity more a subset of Britishness and less individually Scottish. All of this had an impact on young James and his view of the world.

By 1752 things had calmed down considerably in Scotland, and young James had shown enough promise and potential to be sent to King’s College in Aberdeen. He spent three years in Aberdeen before moving on to spend a year at the University of Edinburgh. The Highland country boy developed a fierce pride in his heritage as a direct reaction to the contempt of his Lowlander classmates. During this time he began to write poetry, though with limited success. His epic poem The Highlander was a good representation of his mentality at the time. It tells of a Scottish hero named Alpin who fights to defend Scotland against Scandinavian invaders with typical heroic fervour. Sadly despite showing some promise it was clearly juvenile work. In later years James would even try to suppress it, as he was obviously ashamed of this initial foray into writing.

James had been sent to university by his town in order to become a schoolmaster for them, and so when he completed his studies he returned to Ruthven. He continued to write, and submitted some poems to Scots Magazine. It’s notable that one of these was based on a work by the Roman poet Horace, though James was quite open in admitting his inspiration. The Highlander was published two years after his return to Ruthven, but unsurprisingly it failed to sell well. He wrote more and more and published less and less, clearly trying to find his voice. And then in 1759 he took a job as a tutor in the town of Moffat, where he met a playwright named John Home. John was a Lowlander and had grown up speaking English, but he had a fascination with Gaelic and Gaelic literature. When he found out that James could speak Gaelic, he badgered him to translate an ancient Gaelic poem for him. This was the beginning of it all.

Blessed be that hand of snow; and

blessed thy bow of yew! I fall resolved

on death: and who but the daughter of

Dargo was worthy to slay me? Lay me

in the earth, my fair-one; lay me by

the side of Dermid.

What James produced was The Death of Oscur, a long poem about two warriors named Dermid and Oscur who together slay a mighty warrior chief named Dargo. (The poem is narrated by Oscur’s father, Oscian.) The two heroes both fall in love with his daughter, an unnamed warrior princess, but she only has eyes for Oscur. So Dermid decides to die, but to avoid the stigma of suicide he persuades Oscur to fight him in a duel that he knows he cannot win. With his best friend dead Oscur is overcome by grief. He tricks the princess into shooting him during target practice and is buried next to his friend. It’s an overwrought and incredibly melodramatic piece of nonsense, so naturally John Home and his friends loved it. They begged James to give them more translations of these Highlander poems, and so eventually he did.

This is where the controversy begins. Part of what made The Death of Oscur such a hit was its uniqueness, but that same uniqueness made it suspicious. James never revealed his original sources, and so the question of whether he actually was translating 3rd century Scottish poetry or whether he was writing most of it himself remained open. There is honestly no way to be sure. The poem bore a great deal of resemblance to The Highlander, and even references a character who appears in it. But the skill of the translator is the heart of the translation, and it would have been natural for James to draw on his knowledge of old tales for his own poetry as well. No folklorist has ever found the original version of the poem though, so the most common interpretation is that James took an old story and using it as a frame wrote the poem upon it. Not an unusual thing for a poet to do (see Tennyson‘s Idylls of the King, for example) but not what he was claiming it to be, either.

If James had lied about Oscur’s provenance, he was now caught in his own cleft stick. The poem was greated with great excitement, but he was now expected to produce more such marvels. He obliged in a trickle that circulated privately in Edinburgh before being collected and sold as Fragments of Ancient Poetry in 1761. This was released at the urging of James’ new friend Hugh Blair, a professor at the University of Edinburgh. Hugh was a professor of Belles Lettres, literally “beautiful writing”. He saw James’ poems as proof of the pure Celtic heritage of the Scottish people, and both felt that like the other ancient peoples the Scottish deserved their own epic poem. Surely the works of the great Ossian, “author” of most of the poems James found, contained such an epic? James hinted at it in the foreword of Fragments. The following year he published Fingal, the poem that would make Ossian (and him) household name.

As rushes a stream of foam from the dark shady deep of Cromla, when the thunder is traveling above, and dark-brown night sits on half the hill. Through the breaches of the tempest look forth the dim faces of ghosts. So fierce, so vast, so terrible rushed on the sons of Erin.

Regardless of its provenance, Fingal is a genuine masterpiece. It tells of how Ireland was invaded by Swaran, the King of Lochlan. (Lochlan was the Gaelic word for Scandanavia, though it had originally been the legendary homeland of the Fomorians. It was the Vikings, the new “Raiders from the North”, who led to it being applied to Scandanavia.) The Irish hero Cuthullin, general of the High King’s armies, is of two minds of how to deal with it. Fingal, king of the Celts who had settled in Scotland, persuades him to give battle to the invaders. Many heroes die in the fighting, and the ghost of one returns to tell Cuthullin that he will be defeated if the fighting continues. Shortly thereafter a messenger arrives seeking his surrender.

“Take Swaran’s peace,” the warrior spoke, “the peace he gives to kings when nations bow to his sword. Leave Erin’s streamy plains to us, and give thy spouse and dog. Thy spouse, high-bosomed heaving fair! Thy dog that overtakes the wind! Give these to prove the weakness of thine arm, live then beneath our power!”

[Cuthullin replies:]

“Tell Swaran, tell that heart of pride, Cuthullin never yields! I give him the dark-rolling sea; I give his people graves in Erin. But never shall a stranger have the pleasing sunbeam of my love. No deer shall fly on Lochlin’s hills, before swift-footed Luäth.”

Cuthullin is indeed defeated, but as he flees the battlefield he spies Fingal’s fleet coming from Scotland on the horizon. Fingal’s forces arrive in time to save the Irishmen from being wiped out, and Fingal himself sees his grandson Oscar’s heroism in the battle. Oscar was the son of Ossian, the bard telling the tale. (This ties the poem to the same legendary narrator as The Death of Oscur.) Ossian is visited by the ghost of Oscar’s mother one night between battles, who warns him in time for him to rescue Oscar from an unexpected ambush. In the final battle Fingal defeats the Lochlanach, but the heroism of one of their chieftains persuades him not to have his men purse and destroy them. He captures Swaran, the two having some history as Fingal had loved Swaran’s sister Agandecca who died tragically. A bard at the victory feast sings of the distant common ancestry of the two Kings, and as a result Fingal releases him on his promise to never again invade Ireland. Fingal and Cuthullin discuss the war before Fingal leaves and returns home to Scotland.

Thus the night passed away in song. We brought back the morning with joy. Fingal arose on the heath, and shook his glittering spear. He moved first towards the plains of Lena. We followed in all our arms. “Spread the sail,” said the king, “seize the winds as they pour from Lena.” We rose on the wave with songs. We rushed, with joy, through the foam of the deep.

If any of this seems familiar to students of Irish mythology, you’re not alone. Not only does the name “Cuthullin” seem extremely similar to “Cuchullain”, but a hero named “Fin(gal)” with a son named Ossian and a grandson named Oscar should also ring a few bells. [1] Charitably it could be said that the Scottish legends he was translating shared common routes with the Irish mythic cycles (as the Celts of Ulster had migrated into Scotland around the 10th and 11th century, and even earlier). On the other hand the battle against Scandinavian invaders puts the story far later than legends of Cuchulainn and Finn MacCumhail, and both are in roles far different from their Irish counterparts. The poem is epic, and well written, but there are definite issues in accepting it as a genuine ancient legend.

The blue waves of Erin roll in light. The mountains are covered with day. Trees shake their dusky heads in the breeze. Gray torrents pour their noisy streams. Two green hills, with aged oaks, surround a narrow plain. The blue course of a stream is there. On its banks stood Cairbar of Atha.

None of that mattered at the time, however, and the poem was a huge success. It swiftly became popular enough that it was translated for the foreign market with the first poem being translated in 1762, the same year as Fingal was released. The following year another epic poem by Ossian was “discovered” by MacPherson. Temora was a sequel to Fingal and had the King of Ireland who Cuthullin had served murdered by an usurper, Cairbar of the Fir Bolg. (The royal palace of Ireland is the Temora of the title.) Fingal invades Ireland to dethrone the usurper and restore his kinsmen to power. Cairbar invites Oscar, who was in Ireland at the time, to a feast in order to force him into a duel and kill him before he can join his father and grandfather. Both men receive mortal wounds in the duel. [2]

The chiefs of Morven sleep far distant. They have lost no son! But ye have lost a hero, chiefs of resounding Morven! Who could equal his strength, when battle rolled against his side, like the darkness of crowded waters? Why this cloud on Ossian’s soul? It ought to burn in danger. Erin is near with her host. The king of Selma is alone. Alone thou shalt not be, my father, while I can lift the spear!

Carbair’s brother Cathmor takes his place as king of Ireland. His army and Fingal’s fight, the fights interspersed with feast and heroic affairs. For example, a princess named Sul-malla has disguised herself as a man and followed Cathmor to war. He discovers her imposture but allows her to remain, and the two become lovers. Ossian’s brother Fillan distinguishes himself as a great hero, and dies a hero’s death. Fillan’s ghost appears to Fingal and tells him to take to the field of battle, which he does after sending a group of heroes to rescue the last remaining legitimate Irish heir. In the battle he kills Cathmor, and the Fir-bolg are routed. Once again Fingal returns home to Scotland.

James closed out his Ossian books with a collected edition of Fingal and Temora plus a few other poems in 1765. By that time he was no longer living in Britain. He had moved to London in 1761 as his fame grew, and in 1764 he had managed to get himself a post in the colonial administration in Florida. James wasn’t a success in the post and returned in 1766, but this did manage to keep him out of the growing argument over the authenticity of the poems. Some historians with fringe theories that matched the poems (such as the idea that the Celts had settled Ireland from Scotland, rather than the reverse) were vocal defenders of them. Thomas Jefferson was also an influential early fan. On the other hand Samuel Johnston hated the poems, while David Hume was initially a fan but became disillusioned when he could not find any evidence they were real. All of this controversy generated sales and interest, and so when James MacPherson returned from Florida in 1766 he found himself a wealthy man.

James may have ended his time in Florida on bad terms with the governor there, but this simply made him an ally of the man’s political opponents. He had lost interest in poetry by this point and moved into politics instead, and became a speechwriter and publicist for Lord Frederick North who became Prime Minister in 1770. That’s not to say he gave up writing. He published An Introduction to the History of Great Britain and Ireland in 1771, a book now best studied as a guide to how misguided people were about history in the 18th century. He then researched a history of the 17th century and the “Glorious Revolution”, but once he had it written he decided it would be too controversial on its own. So instead he published his research as The Original Papers containing the Secret History of Great Britain, from the restoration to the Accession of the House of Hanover. This itself proved controversial, but it diverted the critical attention away from his book based on the papers that he published shortly thereafter.

James also made a tidy sum at this point from acting as the unofficial censor of the London newspapers, ensuring that they published nothing too far out of line with the government’s views. He also became tied in with Indian affairs. At the time his cousin John MacPherson was working for the East India Company, and had become a great ally of Muhammad Ali Khan Wallajah, the Nawab of Arcot. In fact John lost his job for supporting the Nawab in a dispute with the company, and he enlisted James to help him put together an appeal to the Board of Directors of the company. James then used this access to publish a book in 1779 detailing the inner working of the EIC, which caused a great deal of scandal when people found out quite how much politicking was going on.

In 1780 James became the MP for Camelford. Camelford was a “rotten borough” which returned two MPs to Parliament but had only 31 registered voters, all of whom were told who to vote for by their landlord. As a result James was not elected by the people but rather was given his seat in Parliament by his government contacts. His fortunes further prospered as he used his insider knowledge of the East India Company to make a fortune speculating on its activity. In 1783 he used this fortune to buy himself an estate in Scotland, on the banks of the Spey.

Throughout the 1780s Ossian continued to be both popular and controversial. Painters found a rich source of inspiration in the works, and the Romantic tradition in particular matched well with the epic poetry. The Danish painter Nicolai Abilgard produced several works based on scenes from the poems, as did the noted historical artist Angelica Kauffman. The Scottish painter Alexander Runciman painted an entire cycle based on the poems for an estate house in Scotland, though these were lost in a fire. This was part of the larger life Ossian was taking on. Scotland was trying to figure out its national identity in these confusing times, and both James MacPherson and a contemporary poet named Robert Burns were helping it to do so.

Both James and Burns passed away in 1796, with James a few months shy of his 60th birthday. In his later years he had begun promising to release the originals on which his Ossian works were based, but he never did. He died before his poems reached the peak of their popularity. There was one fan of Fingal who would make the poems a national sensation in France, where they were already popular. That fan was Emperor Napoleon Bonaparte. Napoleon had been enchanted by the Ossian poems when he first read them in the 1780s, and the collected works was one of the books he brought on campaign with him. His enthusiasm led to many French artists creating paintings based on the works, and drove their translation into even more European languages. There were some other odd effects from this. Most notably, the man who Napoleon made King of Sweden named his son Oscar after Ossian’s son. As a result “Oscar” became a royal Swedish name and a popular name throughout the country to this day. The name “Malvina” (which James MacPherson had invented entirely) also became popular in Scandinavia for similar reasons, while the name “Fiona” (previously an obscure old Irish name) almost entirely owes its modern day popularity to it appearing in James’ poems.

By the 19th century Sir Walter Scott was forging the new Scottish national identity, and the works of James MacPherson were a valuable material for this work. He personally didn’t think it mattered whether they were genuine or not. If they were, then they were a part of Scotland’s literary heritage. But if they weren’t, they were still, by now, a part of Scotland’s national heritage. For better or worse, Fingal and his kingdom were now the image of ancient Scotland inside the head of the world. And as the Victorian Empire sought to enhance the idea of the Scottish as a warrior race (with army recruitment pursued much more aggressively in Scotland than England), Fingal’s fit perfectly into the spirit they sought.

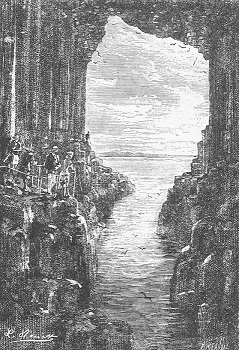

As time went by, Ossian and James MacPherson gradually faded from the public consciousness. Despite Scott’s observation, the idea that it was “all fake” (and the Napoleonic connection) turned public interest in Britain away from the books. Still, the stories behind them lingered and many places in Scotland grew new names based on the Ossian saga. The most famous of these is definitely Fingal’s Cave on the island of Staffa. The acoustics of the cave inspired the The Hebrides Overture by Felix Mendelssohn, which is also known simply as Fingal’s Cave. The poems came back into the mainstream in the 20th century, and the debate over their authenticity continues to this day. Two hundred years later, however, it hardly matters. It’s all “”historic Scottish literature” regardless at this point. Regardless of how “real” the poems are, they are good poems that have evoked genuine admiration. At this point, isn’t that all that really matters?

Images via wikimedia.

[1] “Fingal” also means either “White Stranger” or “Foreign Tribe” in Irish, which is interesting. (And it’s the name of the “county” that contains the northern part of Dublin, as the city was officially subdivided in 1994.)

[2] Yes, this does contradict the previous death of Oscar.