Hugh Glass, American Frontiersman and Survivor

The American frontier was a place of legends, tall tales and wild stories. But among these stories were true tales of extreme human endurance and courage in the face of extreme conditions. One such story became a legend in its own right, the tale of a man who came back from the dead and traveled hundreds of miles in search of revenge. That man was Hugh Glass.

Hugh Glass was born around 1783 in Pennysylvania to Irish immigrants, though not quite the usual sort. His family were what is called Scots-Irish outside of the British Isles and Ulster-Scots within it, descendants of settlers who had come to Ulster from Scotland in the 17th century. In the 18th century a great number of these moved on to England’s American territories, and while most Ulster-Scots emigrants settled in what would become Canada a sizable portion made their homes in the future United States. Young Hugh grew up in the equally young nation of America, and with the world changing so much around him it must have seemed like anything was possible.

Little is known of Hugh’s early life. Scranton was one of the flashpoints for an early interstate conflict between Connecticut and Pennysylvania over the western territories that would later become Ohio. This type of tension shows how all was not just sweetness and light in the early years of the Union. By the time Hugh grew up, the “Northwest Territory” of Ohio and Michigan had been conquered and the frontier had moved further west. That was where he went to seek his fortune.

Our best source for the early life of Hugh Glass are the memoirs of George C Yount, a fur trader who was his friend in the 1820s. Hugh told George some stories of his early life, before he became a trapper and scout. Though he may have embellished them as was traditional for mountain men it was equally traditional for these stories to be at least partially based on fact. According to these stories Hugh had been a sailor in his thirties, working on a merchant ship along the west coast of the Americas. Unfortunately for him his ship fell victim to one of the most notorious pirates of the age, Jean Lafitte.

Lafitte was a Frenchman who had originally been a smuggler but turned pirate when that proved unprofitable. He had been operating off the Americas for over ten years by the time he captured Hugh’s ship, and he would continue to do so well into the 1820s. Hugh was one of the sailors captured along with the ship, and he was offered a stark choice: turn pirate, or be slain on the spot. He chose the later, and entered a life that he would later describe as:

…monstrosities of conduct belonging to a society which has cut itself off from honor and compassion, that outsiders can only understand at the price of forced association.

One of the sources of these monstrosities was the nature of the cargo Jean most often stole. His preferred prey was slave ships operating the “triangle trade” from Africa; and he and his men would relieve them of their cargo of human misery only to sail south to Louisiana and get their own share of blood-money in exchange for human lives. It was brutality heaped upon brutality, with bloody murder just another tool of the trade. Hugh Glass proved to have little stomach for it, and he and a friend began to discuss their dissatisfaction. Unfortunately they weren’t as discreet as they could have been. Soon the other pirates told them that a hearing would be held to decide their fate, but Hugh and his friend were able to escape from the ship to the shore the night before the hearing.

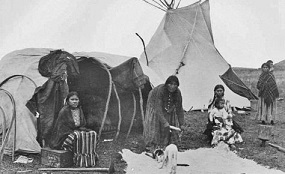

The two men immediately set out away from the coast, though they didn’t know much about the geography of the area. They headed north, living off the land. They were deep in “Indian Territory”, the part of the country still under control of the Native America, so Huh and his friend did their best to avoid being found. The managed this for around a month, and they made it a thousand miles north to Nebraska before they were captured by a group of Skidi, one of the bands of the Pawnee people. Once again, they found themselves facing death.

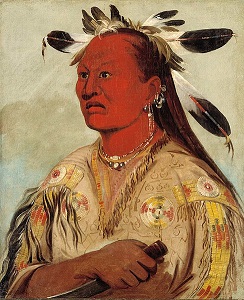

They weren’t immediately killed, and were held prisoner and treated fairly well. However it turned out that this imprisonment had a dark purpose. The Skidi were one of the few bands of Native Americans who practiced human sacrifice, and this is what their captives were intended for. Hugh’s friend was tied to a stake, set alight and then stabbed with burning stakes. Hugh was about to suffer the same fate when as he was being stripped for the stake he discovered a packet of vermilion dye he had stashed away. He presented it to the chief, and the gift was considered precious enough that it was accepted. This made him a guest of the tribe, and he was spared sacrifice. He spent several years living with the tribe, and through them learned the tracking and trapping skills that allowed him to enter the fur trade.

How much of this tale is true and how much is artistic license is naturally quite difficult to say. Though it’s possible that Hugh spent some as a pirate, he probably wasn’t pressed into the trade by Jean Lafitte himself after his ship was captured. At that time Lafitte was the leader of an independent colony in Galveston, and a single attack made on an American merchant by one of his captains was considered a severe enough offense that a Navy vessel was sent down to force Lafitte to leave the island. No attack such as Hugh describes ever happens, so if he was captured and impressed then he was working on a slave ship trading with the Spanish. If this was the case though, it would be natural for him to leave it out of his story.

Similarly, Hugh’s story of his time with the Skidi weaves fact and fancy together. While the Skidi did practice human sacrifice, their victims were not grizzled ex-seamen in their thirties. Their sacrificial ritual was known as the rite of the Morning Star, and involved kidnapping a young girl from another tribe in order to sacrifice her. The details of the ritual are similar to what Hugh states but not the same, making it seem like he was repeating incorrectly something he had heard described. On the other hand, he definitely did spend some time living with the Pawnee, taking a wife from among the tribe and winning some fame for managing to kill a grizzly bear. In fact our first definite record of Hugh comes when he accompanied a Pawnee delegation to St Louis in 1821, and he chose to remain behind in “civilised” society when they returned to the tribe.

In 1822 a general in the Missouri Militia named William Henry Ashley put an advertisement in several St Louis newspapers looking for a hundred men to mount an expedition to follow the river Missouri to its source and stay there for several years trapping animals and harvesting pelts. These men were the core of what became the Rocky Mountain Fur Trading Company. Hugh was not one of “Ashley’s Hundred”, as the founders of the company were known, but in 1823 he was hired by William Ashley to accompany his resupply trip for the expedition. This put him right in the crosshairs for the opening battle of what became the Arikara War.

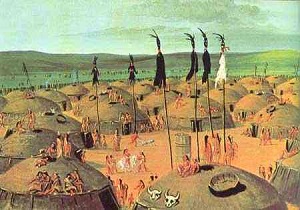

Ironically the Arikara were one of the tribes that the American settlers had originally had the closest (if not the friendliest) relationship with. In fact they were notoriously hostile to white traders, but this was due to the competition they posed. The Arikara saw themselves as the middlemen for trade up and down the river Missouri, and they didn’t appreciate Ashley’s attempt to cut them out of the loop. [1] As Ashley and his men traveled up the river on their resupply mission, they passed an Arikara village (with a population of around 2500) and stopped to trade and parley. They traded muskets for horses, and then took their new animals back to the shore. There Ashley split his group into a shore party (to travel with the horses) and a river party (to travel on the boats). The two groups then settled down for the night, planning to set off in the morning.

Two significant events took place that night. The first was that a pair of trappers, Edward Rose and Aaron Stephens, secretly left the camp and headed into the Arikara village to try and meet some native women. The second came when three Arikara scouts sneaked onto the boat and made an attempt to assassinate Ashley. Luckily for Ashley he was still awake, and he drove them off with pistol fire. This aroused the entire camp, despite the thunderstorm that was breaking upon them at the time. While Ashley was trying to restore order, Edward Rose came running back into the camp screaming that Edwards had been murdered.

Some on the shore said that they should try to swim the horses across the river under cover of darkness, but it was decided to wait until daylight. As soon as the sun rose, though, the Arikara began firing on them with the same muskets they had traded for the day before. In the confusion the trappers on shore made a break for the boats, which then had to try to get away and let the current carry them downriver to safety. Around 14 men were killed, and Hugh Glass was wounded in the leg. We know this from a letter http://hughglass.org/arikara-battle-2/%20he%20wrote%20to%20the%20family%20of%20John%20Gardiner.%20John%20had%20made%20it%20onto%20a%20boat%20but%20died%20of%20his%20injuries%20as%20they%20escaped.%20He%20had%20asked%20Hugh%20to%20let%20his%20family%20know%20that%20he%20was%20dead, and Hugh assured them that:

Master Ashley is bound to stay in these parts till the traitors are rightly punished.

Hugh was healing from his wounds while Ashley distributed that punishment. He called on the US Cavalry for support, in what was at the time the westernmost deployment of American troops into battle. Colonel Henry Leavenworth (who would later found Fort Leavenworth in Kansas) led a troop down to lay siege to the village. He bombarded it with cannon and then negotiated a surrender; disappointing many of his troops who had wished to storm the place. As the army headed back downriver they saw smoke on the horizon. The members of the Rocky Mountain Fur Trading Company who had accompanied Leavenworth had not been satisfied by his actions, and so they had torched the village in retaliation.

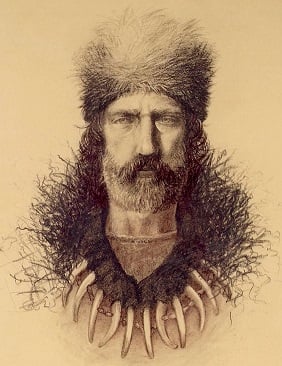

William Ashley was now forced to reconsider his strategy. He had taken on severe debts to finance his company, but now it was clear that he could not just sail up the Missouri to reach the trapping territory. The only other option was to go over the mountains. So that’s what he did, sending out several groups of trappers and eventually stumbling into several prime beaver-hunting territories. Over the next few years he established the “annual rendezvous” system, where his trappers would bring in all their pelts for the year and be paid. For the rest of the year they lived in the wild, becoming the classic American “mountain men” of frontier legend.

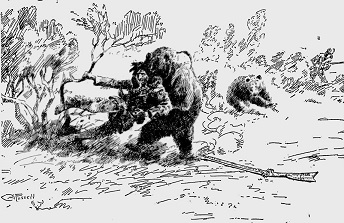

Hugh Glass became one of the first of those legends in the autumn of 1823, while he was part of an expedition that went overland to wind up the old camp, known as Fort Henry after Ashley’s partner William Henry. Seventeen men headed into the forest in early August. A week or so into the trip they were fired on from a distance by Native Americans, killing two of the expedition. It was a few weeks after that when Hugh ran into trouble. His job as an experienced hunter was to keep the expedition supplied with fresh meat by ranging out from them and finding game; but on that fateful morning he found instead a mother grizzly and her two cubs. A female bear with young is notoriously aggressive, and this one was no exception. She charged Hugh and attacked him, and he was only rescued when the rest of the expedition heard his screams and came running to help. They shot and killed the bear, but not before Hugh had received severe injuries. The general consensus was that he wouldn’t survive the night.

Rather than wait around (and possibly be attacked by Natives again) William Henry ordered his men to build a litter for Hugh and bring him with them. It was considered unthinkable to leave him behind on his own, even though they were sure he was about to die. But he didn’t. After two days he was still clinging on to life, still slowing down the group and putting them in deadly danger. So Henry asked for volunteers. Two men to stay with Hugh so that he would not die alone, and then to bury him. For this service the men would receive a bonus of eighty dollars. An experienced frontiersman named John Fitzgerald and a young rookie named Jim Bridger agreed to take on this solemn duty.

Bridger and Fitzgerald stayed with Hugh for five more days, but the tenacious Ulster-Scotsman still somehow managed to cling to life. He barely moved, but his eyes still flickered and his chest rose and fell, rose and fell. John Fitzgerald was a veteran of the forest and he knew that he and Bridger stood no chance if the Natives discovered them. Eventually he managed to persuade the younger man that they had fulfilled as much of their charge as could reasonably be expected. They had only been expected to stay for a day or two, and to stay for five was surely enough. So they laid Hugh’s pallet down next to a stream. They divided his gun, knife, hand axe and tinderbox between themselves. And then they set off to their rendezvous, leaving Hugh behind to die. But he didn’t.

Hugh was still conscious enough to hear the two men discussing him, and when he saw them going away he knew that they were abandoning him. A flame of rage caught light in his heart that they would do such a thing, and that rage gave him the strength to crawl off his deathbed. The cold water of the stream woke him up enough to realise there was one place he might survive. The nearest permanent white settlement was Fort Kiowa, a trading post owned by Joseph Brazeau which had deliberately been set up as a toehold of American capitalism in the wilderness. It was two hundred and fifty miles away, but it was his best hope. So he started crawling.

Determination was a large part of what saved Hugh Glass, but luck played a role as well. About a week into his long crawl he came across a group of timber wolves taking down a buffalo calf that they had separated from the herd. After the pack had gorged themselves and moved on, Hugh moved in and made off with what was left of the carcass. The meat gave him enough food for several days, and he made camp to rest and heal while he ate it. By now he was able to limp rather than crawl, and his pace increased. A second major stroke of luck came when he made it to the Missouri River and met a friendly band of Native Americans from the Lakota tribe. They gave him a hideskin boat as a gift, perhaps because they were impressed that he was still alive. Fort Kiowa was downstream, so Hugh was able to float in relative ease to his destination and his salvation. He limped through the front gate six weeks after Bridger and Fitzgerald had left him behind in the forest.

Hugh planned to spend some time recuperating in Fort Kiowa, but while being treated he heard of a French group of trappers led by Antoine Citoleux (nicknamed “Langevin”) traveling upriver through Arikara territory to Tilton’s Post, a Columbia Fur Trading Company outpost near a village that was home to the friendly Mandan tribe. They thought that the Arikaras had calmed down enough to make this possible. What Hugh cared most about though was that where they planned to trap was not far from Fort Henry, where the two men who had left him to die were headed. So with his wounds cleaned and stitched up he decided to set out with the group. He was able to purchase a rifle and ammunition on credit, as he was well known to be an “Ashley” man. Two days after he had arrived in Fort Kiowa he set out once again, determined to have his revenge.

Langevin and his men knew they were taking a gamble with their journey, and after a few weeks their interpreter Toussaint Charbonneau went on ahead to try to gauge the sentiment among the natives. The trip itself began to run into trouble as strong winds slowed the boats down. About six weeks into the journey Hugh decided to leave the expedition and go overland instead. It was a decision that saved his life, as less than a day after he left Langevin’s group the Frenchmen were attacked by Arikara and wiped out. Hugh was only a few miles away from the Mandan village when he nearly met the same fate at the hands of an Arikara hunting party. Luckily for him a couple of Mandan warriors saw him running and scooped him up onto horseback to save him. Hugh Glass had survived once again.

By now it was late November, and winter was coming down hard on the forest. Where Hugh was is now the state of South Dakota, and the winters there have grown no less harsh than they were in 1823. But Hugh was determined to make it to Fort Henry, so he decided to set off from Tilton’s Post immediately. It took him 38 days to travel the 300 miles to the site of Fort Henry; and when he did he found an abandoned shell. Whether they left a note or if Hugh followed the tracks they had left behind, it wasn’t until three days later on New Year’s Eve that he made it the new Fort Henry.

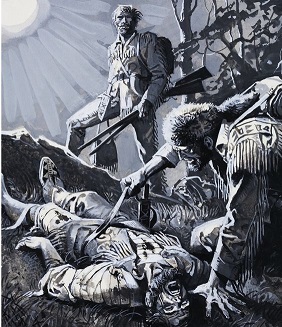

The men of the Fort were celebrating the turn of the year when Hugh Glass walked up to the gate of Fort Henry and asked to be let in. At first the men thought that this gaunt figure bearing the face of a man they thought dead was some ghost come to the feast. As they realised he was flesh and blood, the mood turned celebratory. But then, as he told his story of survival against all the odds, the air grew quiet. The men began to move themselves slightly, until one man was left sitting alone with his head bowed. Young Jim Bridger could not look Hugh Glass in the face, and when Hugh looked down at the man he had traveled a thousand miles to kill his heart melted. Bridger was only 19, barely a man, and Hugh remembered hearing him talk of how he was sending all his pay back home to support his sister since their parents were dead. So Hugh put down his rifle, and told Bridger not to let himself be led astray by bad council again. It was advice that clearly served him well. Jim Bridger would go on to become one of the most famous of the Mountain Men, and his tales of the American frontier remain legendary to this day.

Hugh Glass now had a single target for his vengeance: John Fitzgerald, the man who had persuaded Bridger to abandon Hugh. But Fitzgerald was not in Fort Henry; and in fact he had left the mountain life behind him altogether. He was heading downriver to Fort Atkinson to join the US Army. Ironically he may even have passed Hugh on the way. By now though it was clearly far too deep into winter to set off after him, so Hugh was persuaded to stay in Fort Henry until the spring. He was reinstated on the Company rolls, and went back into service. This service was rewarded when spring arrived and Andrew Henry needed to send his report downriver to William Ashley. The report was being sent to the post office at Fort Atkinson; so now Hugh could get official support for his mission of vengeance. On February 29th 1824 he and four other men set off for Fort Atkinson.

The men headed south for several weeks until they reached the North Platte river, where they made boats out of buffalo hides and set off downstream. At a junction of the river they encountered a Native American camp, and the leader of the Natives called out to them in Pawnee to come and parlay. Since relations with the Pawnee were friendly, they left one man with the boats while the rest headed in to the camp. During the parlay though, Hugh overheard one Native speaking the Arikara language. He realised it was a trap, and tipped off his fellows. At the first chance, they made a run for it. Two were cut down as they ran. One made it away to the river, where he was picked up by the man left to guard the boats. They thought that Hugh had also been killed. But, once again, they were wrong.

Hugh fled inland, and once he was safe stopped to take stock. He had left his rifle on the boat, but otherwise he had his full kit: knife, flint and steel. Once again he set out for Fort Kiowa; not the most direct route to his destination but the one that he decided was safest. At the trading post he confirmed that John Fitzgerald had joined the army and was definitely stationed at Fort Atkinson. And in June of 1824, Hugh Glass finally made it to the fort.

Hugh’s planned revenge didn’t go quite according to plan, though. The Army was sympathetic to his story, but it wasn’t about to let him enact vigilante justice on one of their soldiers. His rifle that Fitzgerald had taken was returned to him, at least. There are different versions of how things went; some stories are that the soldiers had a collection to compensate Hugh and promised that they’d remember Fitzgerald’s conduct. Another had it that Hugh was given an opportunity to speak to Fitzgerald and told him that he should never leave the Army; because if he did then ugh would find him and kill him. However it went it ended the same way: Hugh Glass walking out of Fort Atkinson with his vengeance unfulfilled.

Hugh decided to move on from this area, perhaps to avoid the temptation to go back to Fort Atkinson, and traveled west. There he became a partner in a fur trapping expedition down south to New Mexico. He spent several years there, having more misadventures. On one occasion he and his group spotted a lone Shoshone woman down by a river. They approached looking to trade with her, but when she saw them she let out a yell and a group of braves just over the ridge attacked them. Hugh had an arrow embedded in his back as he fled, and there it had to stay while the group traveled 700 miles back to their home base at Taos. There someone was able to operate and remove it, though Hugh took several months to heal. After that he decided to move on from New Mexico and headed to Yellowstone.

Hugh became somewhat of a leader to the independent trappers in Yellowstone, representing them at various rendezvous with the fur companies. He spent six years in Yellowstone before he finally met his end. Exactly what happened isn’t known, but it’s assumed that while crossing the frozen Yellowstone river in the winter of 1833 he and two companions were ambushed by a group of Arikara who were scouting the area. Their corpses were found several days later. In a postscript, later that month a friend of Hugh’s named Johnson Gardner was leading a group of trappers who encountered some purportedly friendly Natives. While the Natives were warming themselves at the fire, Johnson noticed that one of them had Hugh’s rifle. A fight broke out, and when the men were unable to explain why they had Hugh’s gun Johnson tortured and killed them.

Hugh strove to shout, to give the lie

To those within ; but could not fetch a sound.

Just so he dreamed of lying under ground

Beside the Grand and hearing overhead

The talk of men. Or was he really dead,

And all this but a maggot in the brain?

– The Song of Hugh Glass, by John G. Neidhardt

Hugh’s trek across the wild Western frontier in search of vengeance was the sort of things legends were told of, and it soon became one of the staple great tales of American survival. One of the first written versions of that legend was in 1915 with The Song of Hugh Glass, part of The Cycle of the West by John G Neidhardt. This was a project to cast legends of the American West in the form of heroic sagas, and Hugh’s story definitely fit the mold. Neidhardt’s poem played fast and loose with the facts in service of the story, but a few years later a more authoritative source emerged. A friend of Hugh named George Yount had given his memoir of life in the trapping days to a Catholic priest sometime in the 1850s. The priest had written down all of Yount’s stories, in which Hugh Glass was a major figure, but had never published them. They were rediscovered in 1923 and published, which gave some historical backing to the legend. From there on Hugh took his place in the pantheon of Western myths, and versions of his story have appeared on stage and screen throughout the years. The most noteworthy was probably the 2015 film “The Revenant”, based on a 2002 novel and starring Leonardo DiCaprio. The film (which earned DiCaprio an Oscar for his portrayal of Hugh) plays fast and loose with the truth of the story, but isn’t that the spirit of the tall tales of the Old West? In any case it seems like the legend of Hugh Glass, like the man himself, isn’t ready to lay down and die just yet.

Images via wikimedia except where stated

[1] In an odd coincidence, the Arikara tribe had begun several centuries earlier as a splinter group from the Skidi Pawnee.