Horatio Bottomley, British Politician and Fraudster

Horatio Bottomley was born in the East End of London in 1860. He had only one sibling – an elder sister named Florence. When he was three years old his father, an ex-tailor named William, died in Bethlehem Hospital (better known as Bedlam). The following year his mother Elizabeth died of cancer. Her brother William Holyoake took the two Bottomley children in at first, while her other brother George Holyoake contributed to their upbringing. William was a single artist though and the brothers decided that his studio was not a good place to bring up two small children. So the pair were fostered out together. This lasted until 1869, when the foster parents adopted Florence and kicked Horatio out, sending him to an orphanage.

The orphanage wasn’t a pleasant place for a young boy, and Horatio didn’t enjoy his time there, but it wasn’t quite the hellish experience the phrase “Victorian Orphanage” conjures up. Arguably Horatio got a better education than he would have outside it, and he did well in sporting activities. In later life he even revisited and supported the orphanage. He didn’t like it enough to stop him leaving as soon as he was able though. He left as soon as turned fourteen, not even bothering to fill in the necessary paperwork (leading to a story that he “ran away”).

For the next few years Horatio traveled around the south of England. He had a short-lived stint in Birmingham as an errand boy, and then apprenticed as a wood engraver in London. When that didn’t take with him then he moved to Brighton where he worked in a jeweller’s shop for a while. In 1877 he decided to return to London, where his sister and uncles lived. He found work as an office boy and at his uncle George’s suggestion enrolled in a course to learn shorthand, a skill which landed him a job at a company named Walpole’s which supplied shorthand writers to legal firms. And then in 1880, at the age of only 20 years old, he got married.

Eliza Norton was a dressmaker’s assistant and the daughter of a debt collector. Not exactly a socially ambitious marriage for Horatio, but she was pretty and proved a supportive wife to Horatio. She gave him a daughter, and more importantly she tolerated his many, many infidelities over the next fifty years. His marriage also made him respectable enough to be given a partnership in the shorthand company, where his immense natural charm and apparent business acumen had clearly impressed the owners. But Horatio had bigger ambitions than just running a shorthand firm. And he saw two routes to achieve them – publishing, and politics.

Horatio’s uncle George Holyoake was an outspoken secularist, and in 1842 he had been the last person in Britain to be convicted of blasphemy in a public lecture. [1] One of his allies was Charles Bradlaugh, who became a mentor to young Horatio. [2] Bradlaugh was an active pamphleteer (he was prosecuted in 1877 for publishing one promoting birth control) and this was Horatio’s first exposure to the world of publishing. It was a growth industry in the late 19th century, and in 1884, just after receiving his partnership, Horatio made his first break into it.

At the time there was a tradition of local debating societies that took as their topics the same topics being debated in Parliament at the time. Parliament’s debates were published in Hansard, named after the publisher who first held the contract to print them. Horatio realised that many of these local societies would be keen on the legitimacy having their own Hansard would grant them, so he was able to get a contract to print this for the Hackney and Battersea societies. Sales weren’t huge, but local firms were keen to advertise and in 1885 Horatio was able to springboard this into creating the Catherine Street Publishing Association. This small firm would found several magazines and newspapers, of which the most well-known is the nowadays world famous newspaper The Financial Times.

Horatio’s rising star caught the attention of his uncle’s associates in the Liberal Party, and they asked him to stand in a by-election in Hornsey in 1887. [3] He wasn’t expected to win, as Hornsey was a solid Conservative stronghold, but they wanted to see how he’d acquit himself. The answer was “well enough”, and he received a letter from William Gladstone, leader of the party, congratulating him. This may also have helped him gain the contacts that let him escape a nasty setback when he and his partner had a disagreement and broke up the firm, resulting in him losing ownership of the papers he was publishing. This could have been disastrous but he kept ownership of the printworks and managed to get the contract to publish Hansard – the real one this time. That was a solid enough contract to let him raise capital and found a new company, which he floated on the Stock Exchange for a cool half a million.

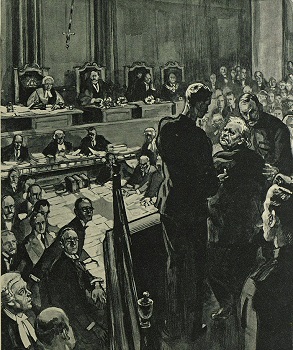

The possibilities offered by this flotation seem to have gone to Horatio’s head, and he quickly began playing fast and loose with the company finances. A board of directors made up of illustrious names gave him cover and were pliable enough to go along with his schemes, which included siphoning funds into his own pockets by buying new printworks at inflated prices and acquiring funds for fictitious deals in Australia. While doing all this Horatio neglected to find any real new revenue streams for the company, though he lied in his first end of year report by declaring a profit and paying a dividend which cleaned out the company’s cash reserves. At the end of the company’s second year in operation it wasn’t able to pay the interest on the loans Horatio had taken up and it was declared insolvent. Horatio had been standing for Parliament again, but forfeited this by declaring himself bankrupt. This didn’t save him from investigators who discovered that a hundred thousand pounds of company money had found its way into his pockets. As a result he was arrested and was put on trial for fraud.

Rather than the end of his career, Horatio Bottomley’s trial for fraud would prove to be the first of his finest hours. The evidence against him was overwhelming, and the case would seem to be over before it began. He was helped by the complacency of the prosecution, who didn’t bother presenting all of their evidence against him and who managed to annoy the judge with their blase manner. In contrast, Horatio’s charm and wit managed to get the judge fully on his side, as he argued that what he was being accused of was standard industry practice, that the prosecution was deliberately understating the amount he’d had to spend on expenses, and that the whole thing was an attempt on the part of the official receiver to gain prestige by bringing down his company. As a result the judge summed up in his favor and Horatio was, against all the odds, acquitted.

Horatio’s surprise acquittal gave him a huge deal of prestige, and earned him a reputation as a financial whizzkid – one he hadn’t really earned, but which would turn out to be not undeserved in the long run. After sorting out his debts and bankruptcy, Horatio swiftly rebuilt his fortune through dealing in West African goldmining shares and early vulture capitalism – picking up failing companies at a bargain price and then ruthlessly restructuring them into profitable entities. Within four years he’d made enough money that he was able to offer £250,000 to the creditors of his previous failed company, a gesture that won him a great deal of public acclaim. He played up to this by living the expected lifestyle of a millionaire – racehorses, mistresses and a mansion in Sussex. His wife lived in Monte Carlo, but Horatio didn’t get lonely – he always had at least two or three “lively, petite, blonde, working-class girls” living in rented flats and being showered with gifts. Indeed, one of the main hurdles his political managers always faced was

As the scandal of his bankruptcy and fraud trial didn’t stick, Horatio had no real difficulty getting back into politics. In 1900 he stood for the Liberals again and was defeated by only 280 votes. One opposition newspaper did bring up his past, but a successful suit against them for libel removed that weapon from his opponents. Perhaps in order to help these political ambitions, Horatio decided to get back into the newspaper business. In 1902 he bought a London paper called The Sun. (That shouldn’t be confused with the modern paper of the same name, as Horatio sold this one in 1904 and it closed down in 1906). In 1906 Horatio finally managed to achieve his ambition of winning a seat in Parliament in the General Election that January.

Though Horatio faced some disdain in parliament, he soon managed to use his trademark charm to win people over. It helped that he didn’t take himself too seriously, and that he did have a solid vision for improving the country. In fact, many of the things he proposed in Parliament (eight hour working days and old age pensions, for example) are now considered not only good ideas but as part of the basic fabric of society. He didn’t cleave to the Liberal Party that had got him elected though, and wound up refusing to follow the party whip and instead became an affiliated Independent. This might have been informed by the level of support he was getting outside Parliament, because the same year he entered Parliament he had founded the magazine that would remain his most famous accomplishment – John Bull.

John Bull was named for the figure most often used as an avatar of England – a stout man in top hat, white trousers, black tailcoat and Union Jack waistcoat. He had been created in the 18th century as a satire of the stereotypical country squire, but had soon been adopted by political cartoonists and had become a symbol of national identity. The name had originally been applied to a magazine in 1820, but was now defunct until Horatio took hold of it. As you might expect, John Bull was a magazine with a distinctively patriotic and jingoistic bent. Add in some of the “yellow journalism” perfected in the USA and you had a magazine that would set the template for a lot of modern British journalism.

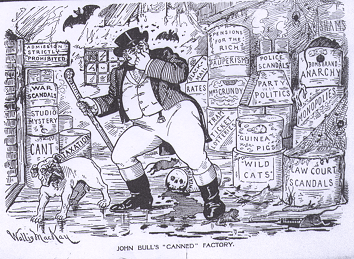

It took a while for John Bull to reach this stature though, and at first it was just another vehicle for one of Horatio’s schemes. This time the alleged plan was for readers to put a £10 “investment” into the magazine, in return for which they would receive “premium content”. Naturally Horatio played fast and loose with this scheme, and in December of 1908 he was put on trial again for having reissued the same set of shares multiple times. Once again Horatio’s charm won the courtroom over, and once again he evaded the consequences of his actions. In 1910 he was re-elected to Parliament and it seemed that he was untouchable. But then in 1912 one of the victims of the John Bull investment swindle managed to win a judgement against him for £49,000. When Horatio was unable to pay it revealed the precarious real state of his finances. He was £233,000 in debt, and had to declare himself bankrupt for a second time. In a further twist of the knife, this meant that he had to resign his seat in Parliament and his ambition of becoming Chancellor of the Exchequer.

Now officially bankrupt, Horatio still managed to arrange things so that his extravagant lifestyle continued unabated. His main source of income was from lotteries and sweepstakes run through John Bull. These were operated from outside the UK to circumvent gambling laws, and were rarely honestly run. Horatio faced legal charges on multiple occasions when it was suspected that winners were actually his employees or relatives. He managed to dodge these charges though. John Bull itself swiftly rose in popularity, with Horatio claiming a circulation of two million. (The actual figure was probably a still impressive three quarters of a million.) He even tried creating a spinoff aimed at women, Mrs Bull, though this was less successful. Then in 1914 the first World War broke out. And where many saw tragedy, Horatio saw opportunity.

When Archduke Ferdinand was assassinated, John Bull’s opinion had been harsh and direct – Serbia was clearly a nation of anarchists and troublemakers, and Austria should definitely take action against it. However when the continent’s interconnected weave of alliances and agreements led to this meaning war between Germany and Britain, John Bull swiftly changed its tone. Now the “Austrihuns” and the “Germhuns” were the enemy, as was anyone in Britain of Germanic descent. [4] On the 14th September Horatio gave a speech at “John Bull’s Great Patriotic Rally For Recruitment”. He denounced the party system of government, and declared that the war could be swiftly concluded if all power was placed in the hands of a man with “the ear of the people”. (No prizes for guessing who his prime candidate was.) He declared that it was the destiny of the “Anglo-Saxon race” to fight this war, and that it could be swiftly won, as long as people fought fiercely enough.

Of course, it wasn’t swiftly won – but that was all to the good for Horatio Bottomley. He made over 340 lectures over the course of the war, declaring that all those who would not go and fight did not deserve to live. (Naturally he didn’t include himself in this, as in his fifties he was comfortably past having to live up to his own rhetoric.) He made the war an explicitly racist one, ordering his readers to physically attack any ethnically German civilians they met, and when the Lusitania was sunk he openly called for the ethnic cleansing of Germans from Europe. His particular brand of poison proved distressingly popular though, and John Bull soon became the most popular magazine in Britain. This wasn’t just down to racist rhetoric – the magazine also exposed war profiteering, poor treatment of soldiers and general government incompetence. It was, for better or worse, the voice of the people.

During the war Horatio ruthlessly parlayed John Bull’s influence for political power. He joined with Noel Pemberton Billing in declaring the existence of “the Unseen Hand”, an organisation of pro-German traitors who sought to undermine the war effort. Conveniently, this meant that any of his enemies could be labelled as members of the Hand. That included the newly formed Labour Party, and as well as denouncing them as traitors he also publicly revealed that one of its founders and leaders, Ramsay MacDonald, was the illegitimate child of a Scottish serving girl. [5] The government used Horatio’s influence over the masses to quell strikes and boost recruitment, though they never did grant his wish for a public position.

After the war Horatio discharged his debts and left bankruptcy. Allegedly this was with the proceeds of his war propagandising, though he always insisted he took no pay for his war work. (Given his previous record, that seems unlikely.) This was in order to allow him to be eligible to stand in the 1918 general election. He ran as an Independent, and won a seat in a parliament in chaos. The Labour Party had won enough seats that the Liberal and Conservative parties had needed to go into coalition to form a government – a fractious alliance between two old enemies. As a former Liberal who had allies in the Conservative party, Horatio was in a good position to act as a powerbroker. He even made a play at forming his own party, and though he wasn’t quite able to manage that he did form an alliance with several other independent MPs who agreed with his views on privatisation and the restriction of immigration.

Horatio’s downfall began with a scheme not unlike many he’d run in the past. He was in the process of losing control of John Bull (he’d made a pre-war partnership to finance it and was being squeezed out). He was trying to acquire new papers, but he needed capital. So he started a “Victory Bonds” club. The government had issued £10 bonds to raise funds to restimulate the economy, and Horatio’s Club allowed people to buy in for a pound with prizes drawn each year to be paid out of the interest on the bonds. It was a reasonable scheme, and if he’d ran it honestly there was no way Horatio could have lost money on it. Of course, he didn’t run it honestly. After a while, public unease led to some people pulling out of the club – which wouldn’t have been a problem, cash in their bonds and pay them off, except that not all the bonds had actually been bought. A lot of the funds paid in went straight into financing his newspapers, rather than going to buying bonds.

Recognising the signs, a former partner of his from his old lotteries referred to the Victory Bonds Club as “Horatio Bottomley’s latest swindle”. Horatio foolishly sued the man and lost, which led inevitably to an investigation and his own trial for fraud. After having dodged prosecution so often, Horatio might have expected this to be another chance to show off in court and walk out a free time. However, there was at least one major difference this time. Horatio had developed a serious drinking problem – bad enough that he actually had to negotiate a fifteen minute break each day to allow him to drink a pint of champagne and stave off withdrawal. As a result, though the prosecutor was far more adept than any of his previous opponents he later commented: “It was not I that floored him, but drink”.

Horatio received a seven year sentence for his frauds, and when his appeal failed he was automatically expelled from the House of Commons. He served his sentence in Maidstone Prison, and after five years he was released in 1927 on probation for good behaviour. His reputation was in tatters though, and as that had always been what he traded on he was left in dire straits. He tried to return to his greatest days by founding a magazine called John Blunt, a recreation of his old John Bull and competitor to its modern version. Nobody was interested in buying it, though, and the magazine folded within the year leaving him bankrupt once again. In 1930 his wife Eliza died. They had lived separate lives for many years, but her death meant that family members who had felt obliged to support Horatio now were free to cut him loose. This might be why he was kicked out of his Sussex mansion, or it might have been because it ended up belonging to his daughter’s ex-husband after they divorced and she remarried.

Horatio wound up relying on the charity of one of the same women he had showered with gifts decades before – Peggy Primrose, the one mistress who had stood by him through the years. Peggy was an actress and she might have been the one who got him his last public appearance, a one man show at the Windmill Theatre where he told stories of his life and recreated some of his greatest speeches. Reports vary as to how this was received – some say that he only succeeded in baffling the crowd at the shows, others that he was popular enough that he might have been able to spin yet another fortune out of his stories. It was a moot point – his health went into decline, and in 1933 at the age of 73 he died. A large crowd attended the funeral, where he was lauded for the contribution his poisonous brand of patriotism had made to the war effort. In accordance with his wishes, he was cremated and had his ashes scattered in Sussex. He was remembered as a symbol of wasted talent, a man who had all his achievements destroyed by his own corruption. In the end, everything he built was like his ashes, just dust in the wind.

Images via wikimedia except where stated.

[1] Though blasphemy remained a criminal offence in Great Britain until 2008, and still is in Northern Ireland. (And possibly Scotland – the law is contradictory and has never needed to be clarified.)

[2] The pair resembled each other, which led some to speculate that Bradlaugh could be Horatio’s real father as he had been a friend of Horatio’s mother. There’s no actual evidence of this, but Horatio did encourage the gossip as he considered the stigma of illegitimacy less than the stigma of having a father die in Bedlam.

[3] Noel Pemberton Billing would stand for the same seat in the 1940s – one of several parallels between him and Horatio Bottomley.

[4] Except the Royal Family, of course.

[5] This led to a letter Ramsay received that was a weird mix of death threat and support: “For your villainy and treason you ought to be shot and I would gladly do my country service by shooting you…But the assault [Bottomley] made on you last week was the meanest, rottenest lowdown dog’s dirty action that ever disgraced journalism.”