Fred and Maria Manning, a Murderous Married Couple

Marriage is a tricky business, even in a legal sense. Victorian law treated the wife as the servant of the husband, which among other things meant that a wife killing her husband was (up until 1828) actually guilty of “petty treason” and liable to be burned at the stake. Even after that stopped being law, it still meant that a wife could not be considered to be guilty as an accessory “after the fact” in murder. It was her duty to help her husband cover up his crime, in that case. But if she helped him plan and commit the murder, then she was guilty of a crime. It was this legal distinction that the fate of Maria Manning hung on, when she and her husband Fred stood trial.

Frederick George Manning was born probably around 1819 in Taunton, the county town of Somerset in south-east England. He was the eldest son of a sergeant in the local militia who worked as a toll-keeper and then kept a pub in Taunton called The Bear. Fred himself went to work on the railways, a job which took him into London and eventually got him a job as a guard on the Great Western railway. His father died in 1845, leaving most of his property to Fred’s mother, with it to pass to Fred after her death. Fred himself inherited some money as well, and allegedly had around £400 in savings by 1847 when he first met Maria.

Maria was born as Marie La Roux in Lausanne in Switzerland in 1821. Her parents died sometime before the mid 1840s, and she moved to England to take up work as a servant. She changed her name to Maria when she did so, as it was easier for her various employers to process. Later writers (most notably the proto-pulp writer Robert Huish) dealt with the lack of any details about her early life by simply making them up entirely. Huish gave her fervently Catholic parents who destined her for the nunnery, and a bandit lover named Montano who seduced her away from this life of virtue. Maria then (in his accounting) became the maid for an Irish couple named Wentworth, and naturally had an illicit relationship with Mr Wentworth. All entirely fictitious, of course, but it sold a lot of books.

Maria’s first verifiable appearance comes in Devon in 1843 at around the age of twenty-two. She was a maid for Lady Anna Palk, the wife of the MP Sir Lawrence Palk. By her later accounts at this time she was already acquainted with one Patrick O’Connor, an immigrant from Thurles in County Tipperary. Despite being twenty years her senior, Patrick would be Maria’s on-again, off-again lover for the next six or seven years. Patrick was a crooked customs inspector who combined smuggling with money-lending to lucrative result. Some writers think the pair met in 1846, though, after Lady Palk had died and Maria had moved on into the service of another minor noble named Lady Blantyre. Patrick was traveling to France on holiday, and Maria to meet her mistress, when the pair met on board ship and began their romance. However it happened, the Irishman and the maid dallied together, never in a serious relationship but always orbiting one another.

Fred entered the scene as Patrick’s rival some time in 1845, and probably met Maria while she was traveling with Lady Palk on the Great Western Line. The two men remained involved with her after she moved into Lady Blantyre’s service and took up residence in Stafford House in the west end of London. This was one of the great stately homes of the capital, where the Duke of Sutherland (Lady Blantyre’s father) resided. Queen Victoria was a frequent visitor, and Maria was witness to the richest people in the British Empire living their luxurious lives. Both Patrick and Fred took great delight in telling their friends that they were off to see Maria at Stafford House, though of course their visits were confined entirely to the servant’s quarters.

Maria’s letters to Patrick show her frustration at his refusal to propose marriage, which might have been why she accepted Fred’s proposal in 1847. Fred in part seems to have based this proposal on his “prospects” of inheriting from his mother, though he may have exaggerated the amount he was going to get from her. Whatever the reason, Maria accepted and the pair were married in St James’s Church in Piccadilly. One of the guests was a great friend of Fred’s, a fellow guard named Henry Poole. Henry would turn out to have an unexpected influence on the Manning’s lives. Patrick was not a guest, though he did make his mark on the newlyweds when he sent a letter to Maria, shortly after the wedding, declaring his eternal love and claiming that he had been about to propose to her before she had married Fred. This was probably not true, but it was a dark seed that helped to poison Maria’s married life.

The normal thing would have been for Maria to stay on in her position for a time, and then to retire when she and Fred began their family together. However this was thrown into disarray when Fred was fired from his job at the Great Western. Exactly why he was fired was not something they chose to make public. Later speculation claimed that he had been implicated in a robbery and though there was not enough evidence to charge him he was dismissed on suspicion. This speculation may have been informed by later events, though. With Fred cut loose, the pair considered their options and decided to return to Fred’s home town. Taking his savings and inheritance (and perhaps a parting gift from Maria’s employer) the couple bought an inn in Taunton called the White Hart. There the pair enjoyed an uneasy married life. Later reports claimed that Maria went off to stay with Patrick several times, and that Fred was acquainted with more than one lady in town. Whether any of these rumours were true or not, the pair did stay together for the most part.

The beginning of the end came on New Year’s Day, 1849. While the Great Western train from Plymouth to London made its journey, somebody broke into the mail car and raided all the mail bags. A large amount of valuables were stolen, and estimates of the haul at the time amounted to £4000. This was a lot back when someone could live comfortably on £100 a year. There were no suspects and the criminals could probably have got away with it, but they were foolish and tried the same trick on a different train the next day. This time it was the train going in the opposite direction on the same line, but unfortunately for them it had a much smarter guard. As soon as he noticed the theft, he realised that the mail car could only have been accessed from the first-class compartments, so careless of any complaints he ordered them searched. In one cabin they found masks and a grappling hook, clear evidence against the occupants. They were arrested and charged with both robberies. One was named Edward Nightingale. The other was Henry Poole.

The media, fascinated with both trains and crime, lapped up the story of these robberies. The Mannings were drawn into the investigation almost immediately, as both men had stayed at their inn and Nightingale had used Fred’s name as an alias several times. They were cleared of involvement, but soon found themselves facing a much more serious charge; one that was not criminal but that broke a far more fundamental law. Some newspapers began repeating a story that the authorities had been warned in advance that this crime was going to take place, and this story soon shifted into a fairly unambiguous implication that Maria had tipped off the police in order to take revenge on her husband through his friend for his infidelities. The fact that this didn’t square at all with how the men were caught is irrelevant. Business at the White Hart went into a nosedive. The respectable avoided it because of criminal associations, the disrespectable because they thought Maria Manning was “a grass”. They were forced to sell the inn and move back to London.

The failure of the inn seems to have also led to some serious cracks in their marriage. They briefly owned a pub called the King John’s Head in Kingsland Road, but that didn’t last either. Eventually they settled in Minver Place in Bermondsey, where Maria found work as a dressmaker and they took in lodgers to make ends meet. One of those lodgers was a medical student named William Massey, and he had a disturbing encounter with Fred Manning one day. By now Fred was unemployed and drinking heavily, and began asking John a series of disturbing questions. Questions about the effects of chloroform and other drugs, for example, and whether someone would sign a cheque if you asked them to while they were drugged. The conversation turned even more morbid, and scared John enough that he moved out. Maria was hardly being subtle about her ongoing affair with Patrick, which was now almost more active than her actual marriage. And Frederic was clearly deeply unhappy about all of this. Something was going to give.

On Friday the 10th of August, Patrick O’Connor did not turn up for work at the London Docks. This was unusual, as despite his extra-legal tendencies he was always solid in his attendance record. When he didn’t turn up the next day, one of his co-workers got worried. His name was William Flynn, and as well as being Patrick’s co-worker he was also his cousin. Flynn went to Patrick’s lodgings to investigate, and found two of his friends there. They told them that on Thursday they had met Patrick and he had told them he had been invited to dinner by his girl “Marie”. When they asked his landlady she told them that Maria Manning had visited the lodgings on Thursday and Friday nights, but that she hadn’t seen Patrick on either occasion. That was enough to make William deeply concerned; concerned enough to go to the police.

The police didn’t manage to get hold of anyone at the Mannings until the next day, when they called and found Maria at home. She told them that Patrick hadn’t come to the dinner on Thursday, and that she had called that evening and on Friday to see if he was sick. They asked after Fred and she said that he was at church, and that they were going out that evening so would not be there if the police came round. William Flynn went to visit her on the Monday, with a police officer alongside him, and heard the same story. He was convinced that something had happened to his cousin, and gave out leaflets promising a ten pound reward for any information on him. He also searched Patrick’s apartment and found that the securities and cash that he knew Patrick kept on hand were missing. He began to fear the worst, and this was confirmed on Tuesday when he found out that Maria Manning had been seen leaving her house with luggage and had not returned. The police had been notified, and the manhunt was on.

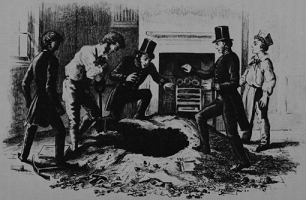

The police kept a watch on the house, but the only visitor was a man who had bought the contents from Fred Manning and was coming to collect them. An initial search of the house turned up nothing, and the police even dug up the back garden without result. On the Friday they noticed that the flagstones in the kitchen had been scrubbed recently, and they decided to lift them up. After finding evidence that the flags had recently been relaid, they continued to dig. About a foot down they found the missing Patrick O’Connor; dead, naked, and swathed in quicklime. [1]

Exactly what happened in the house at Minver Place that Thursday night is unclear. Patrick was murdered, that much seems certain. He was shot in the back of the head, but that doesn’t seem to have killed him. The bullet cracked his skull and traveled under his skin to come to rest just above his eyebrow. (It was speculated that he might have been shot with an airgun, or else that there was an insufficient charge of powder in the gun.) He was then finished off with several blows to the head. Fred would later blame Maria, and Maria would blame Fred. One thing is for certain, though. They buried him together, and then Fred ran away while Maria stayed behind.

There was an immediate public interest in the case, of course, and despite the uncertainty the press immediately focused in on Maria as the murderer. It was simple economics – women killers sold more papers. Soon the general public were regaled with stories painting her as a brazen adultress who had plotted the murder of her lover out of nothing but greed, and who had browbeaten a weak-willed husband into going along. She was also the immediate focus of the police investigations, though that was more because she was easier to trace the movements of. They tracked her to London Bridge Station, where she had left several boxes in the luggage office. These turned out to contain bloodstained clothes, letters Patrick had written her, and letters she had written to Patrick along with some other documents from his apartment. From there she had gone to Euston Station, where she had traveled (first class, of course) to Edinburgh.

Maria had taken lodgings in Edinburgh, where she was trying to convert the stocks she had taken from Patrick’s apartment into cash before she fled the country. Unfortunately for her some of the shares had been reported as stolen, and the stockbrokers she contacted tipped off the police. They had just been alerted by telegraph that Maria Manning was probably in Edinburgh, and suspected that this might be her. So on the same day that the police in London traced her to Euston Station, the police in Edinburgh arrested her at her lodgings. She had been “on the run” for only one week. It took three days for her to be extradited to London (as Scotland had a separate legal system), and the Edinburgh reporters had their day in the sun writing about the lady in the elegant black satin dress.

Fred proved more difficult to track down. After selling the furniture he had made his way to Waterloo Station, where he effectively disappeared. Unlike Maria, Fred was not a distinctive character. “Five foot eight, fair hair, ruddy complexion.” The police released a description and were inundated with mistaken reports from Islington to Dublin. On the 28th August, nearly two weeks into the search, they finally got a solid lead. Fred had stayed in a guesthouse in Guernsey back in March, and the sister of the keeper of that guesthouse recognised him on a steamship. She hadn’t heard of the murder at that point, and didn’t think twice about it until she got off the ship and read a newspaper. The ship had been going on to Jersey, and that was where Fred had holed up. He made plans to flee further on to France, but wound up just drinking and making himself disliked while he stewed over what he could do. He was still in Jersey when the police arrived. It took them several days to track him down, and in fact it was his guilty conduct when he found out they were looking for someone that gave him away. He was arrested on the night of the 30th August, having managed to evade arrest for nine days longer than his wife.

Maria remained silent when she was arrested, but Fred immediately began trying to lay the groundwork for his defense. He asked if she had been arrested, and was delighted to hear that he was. His story was that she was the murderer, and he was “entirely innocent”. This was a foolish tack, given that it would have been impossible for her to lift the flagstones in the kitchen by herself, but Fred seems not to have realised that. The investigators were happy enough to let him run his mouth, and knew that by pitting the two against each other in court they would almost certainly ensure the conviction of both.

The “Bermondsey Horror”, as it was called, took place shortly after the murders committed by James Blomfield Rush, and the press hysteria over that case smoothly transitioned over to this new one. Naturally, most of their fire was turned on Maria. She was attractive, foreign and had served in noble households; it was almost as if she had been tailor-made for the press sensationalists. Most heinous sin of all, she was composed and calm. Or “cold and calculating”, as the papers would put it. Their vitriol against Maria reached such a pitch that it’s a popular myth that it was one of the causes for why wearing black, and particularly black satin such as Maria preferred, fell out of fashion as standard everyday dress for women.

The initial inquest returned a verdict of murder, of course, and the Mannings were committed to trial. One interesting fact that emerged came from William Massey, the former lodger. In addition to the disturbing conversations he had with Fred, he testified that the Mannings had told him that Patrick O’Connor had left Maria most of his property in his will. Evidence also showed that they had purchased a shovel and lime, and so by the time the inquest closed the case was pretty much laid out there. This evidence of conspiracy was important, as the law which assigned so little free agency to married women at the time actually acted in their favour for once here. A wife could not be charged as an accessory after the fact for a murder committed by her husband, as it was presumed that her first loyalty was to him. The trial would need to show that she had pre-knowledge of the planned crime, or that she directly took part in it, or that she had acted on her own initiative in making an attempt to profit from it. Proving that became the focus of the investigation.

The trial took place in the Old Bailey. Maria was represented by William Ballantine, and Fred by Charles Wilkins. Ballantine did his best to try to get Maria a separate trial, by arguing that as a foreigner she was entitled to be tried by a jury made up of half English citizens, and half foreigners. Fred, of course, would have to be tried by an all-English jury, and so the separate trials would be achieved. However this was denied on the grounds that Maria’s marriage made her an English citizen. So the joint trial proceeded. Bloodstains on a dress belonging to Maria and her having paid for the lime delivered before the murder turned out to be the key points in her prosecution, while they took Fred’s guilt almost for granted. His attorney put up a spirited defense, but he had an impossible task. Maria’s attorney tried to use the element of timing to defend his client, pointing out that the last time Patrick was seen alive and the time Maria called at his apartment meant that she couldn’t have been home when the actual murder took place. The prosecution argued that he could have been killed after she returned, and that seems to have satisfied the jury. It took them only forty-five minutes to find both Fred and Maria guilty.

Before passing sentence, it was traditional to ask the prisoners if they had anything to say. Fred did not, but Maria spoke with great vehemence for some time, declaring that there was “no justice and no right for a foreign subject in this country”. She continued to try to speak as the judge passed sentence, which was (inevitably) death for both Fred and Maria. She continued to yell about injustice and proclaim her innocence as she was led away, a stark contrast to the tight control she had kept during the trial. Her mood swung to almost jovial in the carriage back to the prison, and then collapsed into grief she was back in her cell. As a reuslt she was put under watch, in case she tried to escape her sentence by preempting it.

With the trial done the newspapers were free to sum it up and fill in the gaps, and almost all of them concluded (based on no evidence whatsoever) that Maria had planned the whole thing and forced her weak-willed husband to aid her. Despite this judgment in the court of the press, Maria was the only one of the two to make an appeal. While she was doing so there was a brief flare of hope in the form of a rumor that her marriage to Fred had actually been bigamous; that he had been married before and so she was entitled to a separate trial after all. Unfortunately for her this turned out to be false. Equally unfortunately the appeals court confirmed the ruling during the case that she had lost her right to a mixed jury due to her marriage, and so her execution would go ahead as planned. In one last-ditch attempt to escape her fate, Maria reached out to her old noble employers to try to get a pardon issued by the Queen, but her letters were sent back unopened. The so-called great and the good had no pity for one who had formerly served them.

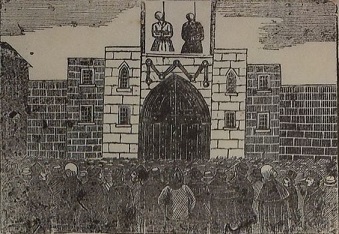

Maria did try to kill herself on the morning of the execution, but her guards spotted and foiled the attempt. Her death was to be public entertainment of the highest order, with a crowd in the thousands in attendance. One of those present was Charles Dickens, who came not to watch the execution but to watch the crowd watching it. He later wrote of the hideous levity on display, describing:

…thousands upon thousands of upturned faces, so inexpressibly odious in their brutal mirth or callousness, that a man had cause to feel ashamed of the shape he wore, and to shrink from himself, as fashioned in the image of the Devil.

In fact, the crowd was so excited that one woman died in the crush, and two men were severely injured. It was before this baying crowd that Fred and Maria Manning were led out. They died together on the hangman’s scaffold. It was the tradition at the time for the bodies of those hanged to be buried in graves on prison ground lined with quicklime, to prevent foul odours. So the Mannings were laid to rest in the same conditions they had hoped to leave poor Patrick O’Connor; one final touch of irony for a most murderous marriage.

Images via either wikimedia or The Woman Who Murdered Black Satin except where stated.

[1] There was a popular folk belief at the time that quicklime would speed the decomposition of a corpse, though in fact by drawing the moisture out it would actually help preserve it. What it would do, and seems to have done here, was to prevent the body from producing a detectable smell from decomposition.