Elizabeth Stuart, the Winter Queen of Bohemia

The murky world of international diplomacy is often overlooked by historians, not least because of the lack of definitive information. It’s much easier to see what a country or person actually did, rather than to speculate on why they did it and how they were pressured to act. While this does make things more definitive, it does tend to deny the influence of many who were not overt rulers. One such figure, obscured and often sidelined, is Elizabeth Stuart.

Elizabeth was born in August of 1596, the daughter of King James VI of Scotland and his wife Anne of Denmark. She was named after her godmother Elizabeth Tudor, the Queen of England. Though Queen Elizabeth had been responsible for executing James’ mother (Mary Queen of Scots), by the time Elizabeth was born James knew that he was the most likely heir to the English throne and was trying to butter her up. (She also had an aunt Elizabeth in Denmark, so the name did have some other history within the family.) Her elder brother Henry had also been named to stress the Tudor connection, as it was James’ descent from Henry VII that put him in line for the throne. A younger brother, Charles, was the only other Stuart sibling to survive past infancy.

In accordance with Scottish tradition the children were fostered out to noble families, something which their mother Anne was deeply unhappy about. When James did finally succeed to the English throne in 1603 Anne used the opportunity to refuse to travel south unless her children traveled with her, which the king reluctantly granted. Elizabeth was delighted by this as she was deeply fond of her brother Henry, though both tended to tease Charles mercilessly. Once they arrived in London she was once again sent off into fosterage, and it was while she was in care that she became a key target of the most famous plot in English history.

The Gunpowder Plot of 1605 was formulated and led by Robert Catesby, though since he was never put on trial it is the government’s scapegoat Guy Fawkes who is the most famous plotter. The main part of the plot was to use gunpowder to blow up the Houses of Parliament while King James and his son Henry were attending the State Opening, killing them and mot of the Protestant leadership of England. Following on from this hammer blow, the plan was to seize Elizabeth while eliminating Charles. Elizabeth would then be made queen and married off to a solid Catholic who could take over rulership of England. However the plot was undone due to clumsy attempts to ensure lords deemed sympathetic would not be in Parliament when it was destroyed. Catesby was killed resisting arrest, but the majority of the plotters were executed via the traditional English tortures of “hanging, drawing and quartering.” [1] The Stuarts were left securely in power, and young Elizabeth was left to her fosterage.

While looking after the young princess was a signal honour for the Baron Harington, it also effectively bankrupted him. Elizabeth was fond of animals, and had pet monkeys and parrots while she was in his household. She received a first class education for the time, learning several languages (though not Latin, due to both its association with Catholicism and her father’s belief that Classical literature was unsuitable for women). Throughout her childhood many suitors petitioned King James for her hand, though only Protestants would ever have been seriously considered. Her mother was keen on Elizabeth, as daughter of a King, marrying someone who would become a king. Unfortunately the only direct heir who came as a suitor was Gustavus Adolphus of Sweden, who would have been a perfect match. Such a marriage would have changed the course of history dramatically (and probably to the great benefit of the Stuarts), but Sweden and Denmark were at war so Queen Anne vetoed this enemy of her native land. Instead it was prospective Princes who had to be chosen among – Maurice of Orange, Frederick of Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel and Victor Amadeus of Spain among them. Eventually Friedrich, Prince-Elector of the Palatinate of the Rhine, was chosen to be Elizabeth’s husband.

The Palatinate of the Rhine was one of the most powerful territories that made up the patchwork confederation of the Holy Roman Empire, one of medieval Europe’s most powerful states. The structure of the Empire was that its territories were ruled by Prince-Electors who chose one of their number to be “King of the Romans”. This king was then officially confirmed by the Pope as “Holy Roman Emperor”. The first had been Charlemagne the Frankish king, but after his line died out it had been taken over by a Germanic king named Otto. By 1600 the empire covered a vast amount of Europe – roughly modern Germany, Austria, Holland, Belgium, Switzerland, and Hungary. (Plus a chunk of northern Italy.) Of the Prince-Electors, the Count Palatine of the Rhine was one of the most powerful. His power had waned though, as over time portions of the territory had been divided off to provide land for younger sons. Friedrich was still one of the most powerful nobles in the Holy Roman Empire though, and was considered by James to be a worthy husband for his only daughter.

Before the wedding took place though, Elizabeth faced the first tragedy of her young life. Her elder brother Henry, who she had always adored, fell ill shortly after Friedrich arrived in England. At the time his disease was a mystery, though the general conclusion nowadays is that it was typhoid fever. If so then it was a sensible precaution to forbid his sister from visiting him, but one which Elizabeth did not take well at all. She even disguised herself as a servant to try to get into his sickroom, but to no avail. On the 6th November 1612, almost exactly seven years after his life had been saved from the Gunpowder Plot, Henry the Prince of Wales died. He was eighteen years old, and had become wildly popular with the people of England. His funeral was a huge occasion, attended by over a thousand people. As a result the twelve year old Charles became heir to the throne.

The wedding of Elizabeth and Friedrich on Valentine’s Day 1613 was one of the most lavish the city of London had ever seen, marked by fireworks and a gigantic mock sea battle on the Thames. The couple (who were both only teenagers, after all) had bonded due to the support Friedrich had given Elizabeth in her mourning, and had attended six of Shakespeare’s plays in the weeks before the wedding. [2] The following month they left England for the Palatinate, where their first child was born on New Year’s Day, 1614. He was named Friedrich Henry.

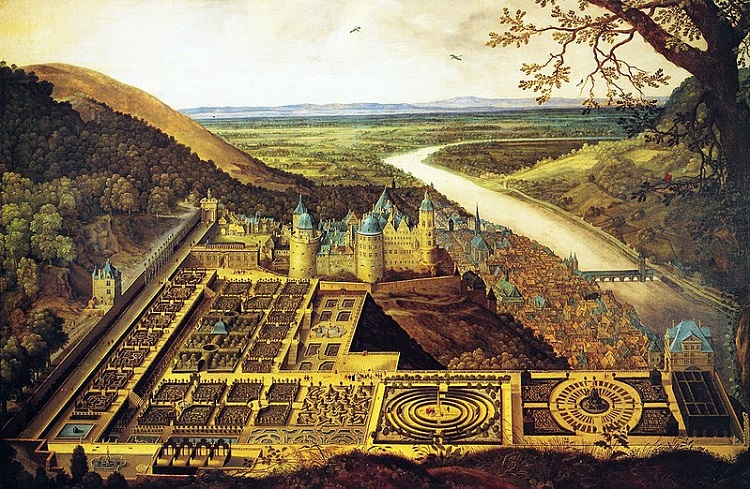

The years Elizabeth spent with Friedrich in the Palatinate were the happiest of her life. Friedrich built her a menagerie in his castle at Heidelberg, along with gardens that were considered the greatest in Europe. They were designed by Inigo Jones, the first great English Renaissance architect, and Salomon de Caus, a Huguenot who had fled to England to avoid the persecution of Protestants in Europe and who had been one of Elizabeth’s tutors. They were known as the “Hortus Palatinus”, and many dubbed it the “eighth wonder of the world”. Young Friedrich Henry was followed by Charles in 1617 and Elisabeth in 1619, and Elizabeth’s German idyll seemed complete. But then it was ruined, like so many things in Renaissance Europe, by religion.

The Holy Roman Empire was where the Reformation had officially been born at the hands of Martin Luther. By the 17th century it was divided between Catholic and Protestant kingdoms and ruled by Emperor Matthias. Though he was a Catholic (as the Holy Roman Emperor would be definition have to be at the time) his policy was one of religious tolerance and rapprochement. It was largely thanks to Matthias that war between Catholic and Protestant rulers in Europe had been avoided, but his death in 1619 seemed to spell an end to that. His heir apparent was his nephew Ferdinand, who was a hardline Catholic well known for his brutal persecution of Protestants. Things looked bad for the Protestant princes of the Empire, of whom Friedrich had become the informal leader. It was this which prompted the Kingdom of Bohemia [3] to offer them the crown in the autumn of 1619.

The kingship of Bohemia was an elected office, but the previous older had been the Holy Roman Emperor Matthias. Legally it was completely possible for it to be given to someone else other than his heir (though Ferdinand had already been preemptively crowned as king). Practically, though, was another matter. By accepting the crown Friedrich would signal unmistakably his intent to break the Protestant part of the Empire away from its Catholic ruler. It was not a decision he took lightly, but he decided to accept the role. He was crowned as King of Bohemia in Prague on the 4th November 1619, and Elizabeth became a Queen.

It turned out not to be the best idea he’d ever had. Bohemia was weakened financially by the incessant wars and border skirmishes with the Ottoman Empire, while the same democracy that had given Friedrich the crown also limited his ability to raise taxes. Neither he nor Elizabeth spoke the local language, so they could not reach out to the people for assistance. Conflicts between the Calvinist preachers he had brought from the Palatinate and the Utraquist preachers of Prague also made a lie of the Protestant unity he sought to promote. [4] Worse, the support from other Protestant princes that he had counted on failed to materialise, as none were prepared to make war on Ferdinand. On the other hand Ferdinand was able to secure the loyalty of the Catholic princes by promising their leader, Maximilian of Bavaria, lands in Bohemia and Friedrich’s title as Prince-Elector.

By the summer of 1620 everything had turned against Friedrich. His father-in-law James could not support him militarily, while his Protestant “allies” signed a separate peace with Ferdinand. The Emperor also pledged to permit Lutherans to worship in Bohemia, undercutting Friedrich’s popular support. (It would take him only two years to break this promise.) In September of 1620 the Emperor easily overran and conquered the Palatinate, and then turned to Bohemia. Friedrich’s underfunded and outnumbered army were gradually forced back to Prague, and eventually made a last stand at White Mountain outside the city. There they were defeated. Friedrich’s reign of Bohemia had come to an end.

Friedrich fled Prague to Silesia. [5] Elizabeth had already left the city as she was heavily pregnant and knew she would not be able to move quickly. She gave birth to a son in January of 1621. The Bohemian nobles left in the city were decimated by Ferdinand, and the democratic systems of the country were demolished in favour of absolute rule. Friedrich then went to the last bit of the Palatinate holding out against Ferdinand, while Elizabeth was offered sanctuary by the Prince of Orange in The Hague (which was the capital of the Dutch Republic at the time). After finally accepting defeat in the Palatinate Friedrich joined her in 1622, exiled from his native land.

It’s commonly said that Friedrich’s nickname of “the Winter King” came from his kingship only lasting a single winter, but it was actually given to him by Ferdinand’s propagandists early on in order to highlight the ill-omen of his November coronation. It stuck, and Elizabeth in turn became the Winter Queen. They set up a government in exile, though they were forced to rely on Elizabeth’s father (and after 1625, her brother Charles) for financial support. Elizabeth had eight more children, for a total of five girls and eight boys, over the next ten years. Tragedy struck in 1629, when young Friedrich Henry was drowned during a river crossing. This was soon followed by a deeper tragedy. Friedrich had fought several times alongside the Swedish king Gustavus Adolphus (the same one who had nearly married Elizabeth many years earlier) in the long-running series of conflicts between Catholic and Protestant kingdoms that became known as the Thirty Years War. However in 1632 when he offered Friedrich his support in reclaiming the Palatinate only if it would be held as part of Sweden, the two men argued and parted acrimoniously. By the end of November 1632, both men were dead – Gustavus in battle, and Friedrich of an infected wound. He was in disputed territory when he died, and though his body was taken away by allies it is unknown where Friedrich was ever buried.

Elizabeth was now a widow, without even a body to grieve over. She went into a deep mourning for three days, refusing to eat or drink and even not sleeping. She emerged from this with a single impulse driving her – to complete her husband’s goal and regain his lands for her family. While he had campaigned in the fields she had written to people across Europe to curry support for him, and in fact an English expeditionary force had landed in Europe just before his death to fight for him. Now that he was dead her brother Charles offered to have them escort her back to England, but she was determined to stay in Europe. It was to symbolise this struggle that in 1636 she had Gerrit van Honthorst create an epic painting of her family, The Triumph of the Winter Queen.

The painting shows Elizabeth in a chariot, leading her three eldest sons while Neptune, Envy and Death are trampled beneath her wheels. (Neptune was probably being targeted due to Frederick Henry’s death by drowning.) Her daughters and younger children act as heralds, with her husband and eldest son watch on from heaven (along with two children who died as infants). Sophia, her youngest daughter, flies overhead with the laurel wreath of victory – a strangely prophetic touch, as it would turn out. The painting was commissioned for Elizabeth’s hunting lodge, where she received visitors. It stood as a testament to her unquenched ambitions. The same year her family (through the English ambassador) received an offer from Emperor Ferdinand – to have half of the lands of the Palatinate restored to them, along with a lesser title. It was a surprisingly generous offer, but for Elizabeth it was all or nothing. She refused the deal.

Over the next ten years Elizabeth did her best to undermine any possible peace deals between the Protestant and Catholic sides involved in the war, in order to ensure her own ends were met. It’s possible that by doing so she extended the war greatly, leading to many more losing their lives than needed to. All of this was on behalf of her son Charles Louis, who in 1637 was (with English funds) able to mount a military campaign to take back his lands. Funds were raised mostly by the Earl of Craven, an English nobleman who had fallen in love with Elizabeth. (It’s unlikely she returned his feelings, but he never pressed the issue.) The campaign ended in disaster in October of 1638, and though Charles Louis escaped his younger brother Rupert (who was already acquiring a reputation as a great military leader) was captured.

Rupert was held prisoner by the Hapsburgs for three years. At first he was offered his freedom and a position as an Imperial general if he would convert to Catholicism, but he refused. During this negotiation he met and became friends with Ferdinand’s brother Leopold, the Archduke of Austria. It was through Leopold’s influence that Rupert was eventually released, after taking an oath to never make war on the Holy Roman Empire again. He returned to England, where he found a land that was gradually sliding towards revolution. Controversially Charles Louis took the side of Parliament against Charles I in this brewing conflict, though Rupert and his brother Maurice were staunch supporters of the king. When open war broke out, these sympathies led to Charles Louis being excluded from the Royalist camp and eventually moving back to the Hague. Rupert and Maurice were generals on the side of the king, with Rupert now establishing himself as one of the greatest generals of the age.

By 1645 Rupert (who had become the commander of the Royalist forces) saw that the English Civil War was all but lost. He urged King Charles to surrender, which led to his dismissal. The eventual defeat of the Royalist forces in 1646 saw Rupert and Maurice exiled from England. It also put paid to any chance of support for a campaign to capture the Palatinate. Charles Louis was permitted to stay in England, and it was widely rumoured that he was hoping for Parliament to give him the throne of England. In 1648 though he received a different offer. Peace negotiations had been ongoing in Europe, and his mother had not been idle in his absence. As part of the Peace of Westphalia, he was granted the southern half of the Palatinate (while Maximilian kept the northern half). It was effectively the same deal that had been offered twelve years earlier, but this time Charles Louis accepted it. Elizabeth had achieved through diplomacy what had failed to be achieved through war, and though she had not succeeded in her original goals it was now enough for her. She planned to retire back to England, but fate had other plans.

A failed attempt to unseat Parliament and restore Charles I to absolute power (in which Rupert took part) ended in failure in 1648, but it was enough to make the rulers of England nervous. They met, and agreed. The king must die. In 1649 Charles I was executed, to the shock and horror of Charles Louis. He left England almost immediately and returned to the Palatinate, which he spent the rest of his life trying to rebuild. His family never forgave him for his dalliance with Parliament, and he was estranged from Elizabeth. She was left reeling by her brother’s death, especially as it was soon followed by the death of two more of her sons and one of her daughters. Though she was a part of the Stuart court in exile, it was only ever on the fringes.

Her estrangement from Edward was only one of the several strained relationships Elizabeth had with her children. Her son Edward married a French princess and converted to Catholicism, which led her to temporarily disown him. In 1657 her daughter Louise also converted to Catholicism, after fleeing to France. She became a nun and later the Abbess of Mountbaisson. Ironically her elder sister Elisabeth also became an abbess, though she was a Protestant one. Elisabeth was a scholar, and one of the few of Elizabeth’s children that she was genuinely close to. Her youngest daughter Sophia was another that she stayed on good terms with, and Sophia married a decently Protestant Prince-Elector in 1658.

In 1660 Charles II was restored to the throne of England, after Parliamentary rule collapsed. As a result Elizabeth was also able to return to England, where she lived in quiet retirement. She was considered one of the few relics of the “old monarchy”, and was now better known as “Rupert’s mother” than as a princess of England in her own right. Rupert, of course, had a major role in the new administration and became one of the leaders in re-establishing British naval dominance. After his retirement he became one of the architects of the British colonies in America and Canada and was also a founding member of the Royal Society, Britain’s premier association of scientists. He never married, though he did have children by mistresses. If he had married, then his descendants would one day have been the rulers of England.

Elizabeth died in 1662, after a bout of pneumonia. Rupert was the only one of her children to attend her funeral, as all the others lived in Europe. By her request, she was buried next to her brother Henry Frederick who she had loved so in life. But though Elizabeth died in obscurity, she was to become of unexpected importance to English history forty years later. As a result of the Glorious Revolution that deposed her nephew James II, a law had been passed barring Catholics from taking the throne. But since neither of Elizabeth’s Protestant nieces, Queen Mary II or Queen Anne, had any children then the succession came back through Elizabeth. The only surviving Protestant child of hers was Sophia, and so Sophia was made heir apparent to the throne when Anne became Queen. Sophia died before Anne did, but since Anne died childless her son George became King of Britain in 1714. Her family may not have been able to hold on to Bohemia, but in the end Elizabeth did prove to be the root of a royal dynasty. For all monarchs of England since then have traced their claim to the throne of England back through this line, and thus through the Winter Queen Elizabeth Stuart.

Images via wikimedia.

[1] Despite Guy Fawkes being burned in effigy in remembrance of the plot, none of the conspirators were executed by burning. In fact, Fawkes even managed to escape the tortures that his fellow conspirators suffered – he jumped from the scaffold he was to be “half-hung” upon, and broke his neck.

[2] Shakespeare himself was still alive at the time.

[3] Roughly, the modern Czech Republic.

[4] The Calvinists were radical in their new doctrine, while the Utraquists remained Catholic in almost all but their refusal to acknowledge the Pope.

[5] A defunct country with lands now split between Poland, Germany and the Czech Republic.