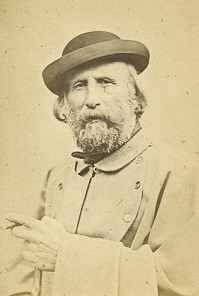

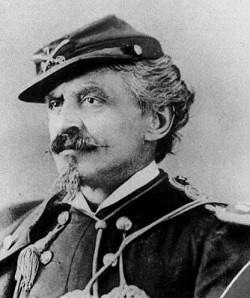

Charles DeRudio, Aristocratic Assassin and US Cavalry Officer

The early life of Charles DeRudio reads a bit like historical fantasy. Perhaps it was – he wasn’t a humble man. However given that the later and even more improbable events of his life are thoroughly documented, it may be that everything he would claim about the first twenty years of his life were just as true. According to Charles, then, he was born in 1832 in the town of Belluno as Carlo di Rudio. His parents were minor Italian nobility, though his father’s title of Count was less significant than his wealth. Carlo was the second son, and so wasn’t in line for his father’s title. But the family money still secured him a place at the prestigious Imperial College of Cadets in Milan, alongside his brother Achilles, being trained to fight in the army of Ferdinand I, emperor of Austria. At the time Milan was under the control of Austria, as was most of Italy. Carlo’s path was derailed in 1848, along with many other plans, when Italy rose up in revolt.

Milan was first rocked by protests on New Year’s Day, setting a fitting precedent for what would become known across Europe as the Year of Revolutions. This initial unrest was beaten back, but on the 18th March when news of other revolts in Vienna and beyond reached them then the Milanese rose up again. Though the pupils of the school were all Italians they were still considered part of the Austrin army and were attacked and confined by the revolutionaries. They were rescued by the Austrians, though the army were then forced back from the city. Carlo and Achilles accompanied the army, but the atrocities they saw the foreigners commit on the way turned them against the Austrian cause. The final straw was when they saw a young woman raped and murdered by one of the soldiers. That night the two men fled the camp, after meting out their own rough and very final justice on the killer.

The two young men joined up with the revolutionary cause, though poor Achilles wouldn’t be a revolutionary for long. While the pair were fighting in Belluno north of Venice he was infected by cholera and died. Carlo was grief-stricken but determined to fight on. He headed to Rome, where the leaders of the revolution had gathered. The greatest of these was Giuseppe Garibaldi, and by Carlo’s account he became a member of the great man’s staff. Rome had previously been part of the Holy See ruled by the Vatican, but the Pope had fled the war and so the Holy See had declared itself the Roman Republic. Garibaldi and his men hoped to make this the beginning of a unified and free Italy, but they were about to be betrayed by the one European leader they thought they could count on. Louis Napoleon Bonaparte (nephew of the famous Napoleon) had just been elected President of France. In his youth he had lived in Italy and had fought alongside Garibaldi in the Carbonari, a secret society of bandits dedicated to Italian independence. However Louis had been elected on a strong Catholic vote, and so he felt obligated to take France into war to restore the Vatican’s rule of Rome. A French army besieged the city, and eventually Garibaldi and his army agreed to surrender it in exchange for safe passage (which was granted). This brought to an end Carlo’s revolutionary exploits.

Quite how Carlo wound up in London six years later is somewhat unclear. He was (as a deserter) under sentence of death in his Italian-controlled homeland, and so could no longer return there. One story was that he was captured and imprisoned by the French after Rome, then escaped. Another more far-fetched story has him working for the resistance against Austrian rule, and being almost captured by police when transporting funds for the revolution. He escaped the police by abducting a rowboat at gunpoint and forcing the owner to row him across Lake Geneva. Yet another had him leaving from the south of France to emigrate to America, but being shipwrecked off the coast of Spain. However it happened, London was a natural place for him to wind up. At the time the city had thrown open its gates to the refugees of war-torn Europe such as Carlo. In December of 1855 he married an English woman named Eliza Booth, and the following year they had a son (named Hercule after Carlo’s father). He made a fairly lean living teaching Italian and working as a gardener. And in the evenings he attended meetings with his fellow countrymen, and contemplated what they had lost.

The focus of their ire was primarily Louis Napoleon Bonaparte. Not only had he betrayed his Carbonari oaths, but in 1852 he had declared himself an Emperor, exposing himself as being totally false to his principles. In the eyes of many of these fiery young radicals Napoleon III (as he now styled himself) was the single greatest obstacle to the liberation of Europe. One such radical was Felice Orsini. Orsini had been arrested by the Austrian authorities in 1854 and had managed to escape by sawing the bars out of his cell window and climbing down a rope of bedsheets. This daring adventure had been reported by the British papers and had made him somewhat of a celebrity, so he was warmly received in London. There he contacted those he thought might be sympathetic to his plans, including Carlo, a chemist named Sinom Bernard and Thomas Allsop, a British author. Together Orsini and Bernard devised the instrument of their vengeance – a new type of bomb, a core of explosive surrounded by detonators. This bomb could be thrown and would explode on impact. It was dubbed the “Orsini Bomb”, and would be used by radicals and anarchists to murder dozens of people over the next fifty years. Allsop put them in touch with a firm in Birmingham who manufactured the bombs for them. After testing them in abandoned quarries, they were ready.

Orsini and his gang (including Carlo) rendezvoused in Brussels, and then headed south to Paris on false passports. The plan was to attack Napoleon III on the night of January 14th 1858, when it was public knowledge that he would be at the opera to see William Tell by Rossini. At half eight, as the emperor’s carriage passed through a crowded street, they struck. The first bomb was thrown by a Neapolitan conspirator named Carlo Gomez. He missed the carriage but the explosion from it killed one of the horses and caused it to crash, immobilizing it. Carlo threw the second bomb, but he threw it too short and it landed among the horsemen who were guarding the carriage, killing several of them. The last to throw was Orsini himself, and his bomb actually went under the emperor’s carriage. [1] The underside of the vehicle protected the emperor and empress from the blast, but a policeman rushing to check on them was killed. In the confusion the three men escaped, but all were later captured. Gomez was caught almost immediately, hiding in a restaurant. Orsini was caught up in a sweep – his cover identity as a beer merchant from Kent was blown when someone with a knowledge of English recognised his bad accent. Carlo almost managed to escape, but he missed the last train out of the city by minutes. He returned to his hotel, thinking that he would be safe until the following day. It was while he was in the middle of writing a note to his wife that the police burst into his room and arrested him.

The three, along with a a fourth who had been arrested on his way to the attack, were swiftly brought to trial. They all pleaded guilty. Gomez (who the defense was a weak-willed man under the thumb of the others) was transported for life, the other three were sentenced to death. The execution was scheduled for the morning of March 13th. According to Carlo’s account he was in the shed listening to the crowds cheer Orsini’s guillotining when the message granting his own stay of execution arrived. His wife had written to her MP, who had passed the plea on to Queen Victoria herself. She had written to the Emperor asking for clemency, and as a result Carlo’s sentence had been commuted to the same as Gomez, transportation for life. In late 1858 the two men were loaded onto a transport ship in chains and taken across the Atlantic to the French colony of Cayenne – more popularly known as Devil’s Island.

As you can probably guess from the name, Devil’s Island was not a nice place to be. The French had first laid claim to the territory of Guiana in 1763 and had tried to colonize it normally, but this had ended after 10,000 of the first 12,000 settlers died within a year of tropical diseases. Despite that France had hung on to the territory. It had been conquered by the Portuguese in 1809, but was returned to France via treaty in 1814. [2] In 1852 the emperor Napoleon had first conceived of the idea of making it a penal colony, sending to it the felons and political dissidents who had been sent to France’s galleys in the Mediterranean in previous centuries. As with the galleys, the mortality rate was enormous and the French government didn’t care. Most prisoners sent there had a “doublage” sentence – a certain period as a prisoner (sometimes, though not always, on the infamous Island itself) and then the same period again before they could leave the colony. Very few ever returned alive. Carlo was determined to be the exception – and not by serving out his sentence.

At the time Carlo arrived there were 4,800 people in the colony. The year before there had been 9,000 but nearly half had died in an outbreak of yellow fever. The guards had been as hard hit by this as the inmates, and so security was somewhat lax. The exact details of Carlo’s attempts to escape are hard to pin down (not helped by his tendency to tell the story somewhat differently every time it came up), but it seems that the first attempt (involving a hollowed out log canoe) was foiled when the river he planned to go upstream on was flooded. The second attempt involved gathering a large group of like-minded lifers, including an ex-Navy captain, and seizing control of a fishing boat at the docks. The men sailed west to the nearby Dutch colony of Surinam where they were granted asylum. It was the first successful escape from the prison colony ever. [3]

Carlo made his way back to London, where he went on the lecture circuit talking about his escape. It may have been for this tour that his name was first Anglicized to “Charles DeRudio”. He definitely used that name in 1864 when he and his wife emigrated to America. Charles had been warned that the French government were seeking his extradition and planned to execute him. He was also told that the British government, somewhat miffed at his misuse of the clemency he had been granted, were likely to hand him over. At the time there was renewed rebellion in Italy and Charles did consider joining that, but it was unlikely he would have been able to make it there without being handed over to the French. So like many other European dissidents he headed west to New York.

At the time the US Civil War was raging, and Charles decided to enlist on the side of the Union. He originally signed up as a private, but his military training and experience, combined with his willingness to take command of a unit of black troops, got him raised up to Second Lieutenant. It was a risky posting as the Confederate forces had made a habit of summarily executing any such officers they captured, but Charles did genuinely believe in the cause of abolition and equal rights. He fought in Florida with an infantry regiment and was honorably mustered out at the end of the war when his regiment was disbanded. (Around this time he suffered a personal tragedy when one of his children, a daughter who had been born in England, died of a childhood illness.) He requested a commission in the regular army, which was initially denied due to his failing a medical after the doctor claimed he had an undescended right testicle. Rumor had it that the real reason was that the army generals had found out about his radical past. This was borne out when two other doctors agreed that there was no issue with his right testicle. With that and with the aid of Horace Greeley (founder and editor of the New York Tribune, and a correspondent of Charles) he was granted his commission as an infantry officer. In 1869 the army was reorganised and the number of infantry units was reduced, so Charles transferred into the US Cavalry.

Charles wasn’t popular among the other cavalry officers, many of whom regarded him as somewhat stuck-up and self-aggrandizing. His stories of his noble Italian origins led one fellow officer to nickname him “Count No-Account”. His stuck-up reputation may have been down to the fact that unlike many of them he did actually take his job seriously, and wasn’t given to drinking and gambling. In 1870 he led a company who defended a group of settlers from Indian raiders and was presented with a golden-hilted saber in gratitude. (His acceptance of this gift was condemned by one of his senior officers, Lt Col George Custer.) He was also active in dealing with the oppression of former slaves by the rich whites of the southern regions and was responsible for breaking up at least one Ku Klux Klan group. He was caught up in a minor scandal in 1874 when he arrested a rich land-owner who had prohibited his black employees from voting. The land-owner was a former general in Napoleon III’s army, and some papers claimed that this was Charles acting on his own anti-French agenda. The scandal didn’t stop him getting a promotion to First Lieutenant in 1875, though. That was the rank he held when he was sent to Montana in 1876 in order to assist Custer’s troops at the river of Little Bighorn.

The US Cavalry had begun its operation to pacify the Lakota tribe based on an estimate that the Native Americans only had a force of 800 warriors. In fact the enemy had 2500 warriors in the field, and had already (unknown to Custer) beaten back one Cavalry force. When he encountered what he thought was a native village, he had no idea that he had stumbled across their main encampment. His plan was to attack the “village” and capture the enemy non-combatants for use as hostages. However his forces were outnumbered four to one, and when they attacked the battle swiftly turned into a disaster. Custer had summoned two other Cavalry forces to encircle the village. One force under the command of Major Reno, consisting of three companies and including Charles DeRudio, were beaten back and joined up with the second part (another three companies under the command of Captain Benteen). These six companies (suffering heavy casualties) attempted to hold their ground but were eventually forced to retreat. As for Custer and the five companies directly under his command, they were also beaten back and then encircled by the Native American forces. After a protracted last stand they were eventually overrun and all killed.

During the initial phases of the battle Charles and several of his men were separated from the rest of Major Reno’s forces. Charles was able to gather up several groups of scattered soldiers and send them off towards Major Reno’s position, but eventually he and a few others were trapped in a thicket and cut off from retreat by a group of several hundred enemies. Luckily for them the enemy didn’t know they were there, and they had a ringside view of the fallen soldiers being scalped and looted. When darkness fell they headed off towards Major Reno but at the river’s edge they were attacked by a group of Native warriors. Two of them were mounted and fled, but Charles and a private named Thomas O’Neill were not so lucky. They had to run and hide again, and then spent another two days dodging enemies around the battlefield before eventually managing to link back up with the other forces. On the 29th June, four days after the battle began, Charles was part of the force who traveled to Custer’s position and discovered the remains of his forces. Charles was responsible for counting the bodies – all 212 of them.

Charles remained in the cavalry after Little Bighorn, and received a promotion to captain in 1882. In 1895 he retired from the military aged 64, receiving a retirement promotion to Major. He and Eliza (and their several children) moved to San Diego in 1896. In 1898 he moved to Los Angeles, where he became somewhat of a celebrity for his lifetime of adventures. In 1908, when asked by a biographer of Felice Orsini if there had actually been a fifth man involved in the assassination attempt on Napoleon III, Charles confirmed that there was. In fact he even named the man as Francesco Crispi – a fellow radical who had gone on to become Prime Minister of Italy during the 1880s and 1890s. Was this the truth, or was it just another tall tale from a man well know for embroidering his already extraordinary exploits? Charles took that secret to his grave on the first of November, 1910.

Images via wikimedia.

Note: an earlier version of this page incorrectly included a picture that was not actually of Charles DeRudio. My thanks to Cesare Marino for noticing the error.

[1] It may not have been Orsini who threw this bomb. At the time the French police believed there was a fifth conspirator who they had not caught, and that Orsini (who still had a bomb in his possession when he was arrested) was protecting this person and had not had an opportunity to throw a bomb.

[2] France retains control of the territory to this day and Guiana is actually considered part of the EU. A launch site there is used by the European Space Agency due to its equatorial location.

[3] As the men didn’t escape from the actual Island (which was reserved for what they thought were high-risk prisoners), they don’t generally get mentioned in the record books. The first official “escape from Devil’s Island” was that of Clément Duval in 1901.