Catiline, Roman Conspirator

The further we go back into history, the thinner our window into the past becomes. Our sources dwindle, our material diminishes, and we’re forced to rely on less and less viewpoints to tell us how things actually happened. As a result, it’s often the case that we either knowingly or unknowingly have a very slanted view of things. Such is the case with Catiline, who may have been one of the most notorious and infamous Romans of the Republican era. The problem being that our primary sources about him are his mortal enemies.

Lucius Sergius Catilina, better known as Catiline, was born in 108 BCE. The Sergius family were one of Rome’s oldest and noblest families. Ninety years after Cataline was born the poet Virgil would write the Aeneid, an epic poem that linked the founding of Rome to the Trojan War through the hero Aeneas (who was a Trojan that escaped to Italy). From him and his crew (so the legend went) the founders of Rome were descended, and one of that crew was a man named Sergestus. Historically, the family had been powerful and members had been elected to the consulship to be one of the two men who shared leadership of Rome. However the last one elected to that post had been in 380 BCE, and by the time Catiline was born they were very much in decline.

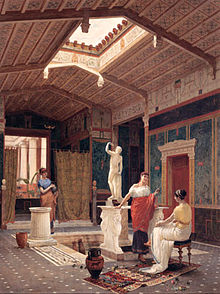

To the Romans the family’s prestige was everything. In effect they practiced a form of ancestor worship, with imagines (sculptures of the faces of honored ancestors) decorating the main hall of their homes. Children would grow up with those faces staring down at them, and be told that one day they might join them; if they brought honour to the family. In a family like the Sergii, that pressure would have been intensified a thousandfold. As such it is certain that young Catiline was raised with one goal in his life, to attain the consulship.

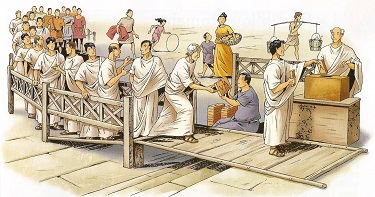

When Catiline was seventeen years old war broke out on the Italian peninsula. Centuries earlier Rome had united Italy, but the citizens of these allied Italian states were not Roman citizens and did not have equal rights under the law. As a result over that time the distribution of wealth had gradually shifted until the Italians had been reduced to a serf class on the lands their ancestors had owned. Naturally this bred resentment and eventually that resentment boiled over into outright rebellion. Catiline came of age halfway through the war and served with distinction. The war ended with the rebels defeated, while the Italian allies who had not joined the rebellion were granted citizenship by a law passed by the consul Lucius Julius Caesar (brother of the famous Gaius Julius Caesar).

The Social War was followed by a war against King Mithridates of Pontus, who tried to take advantage of the turmoil to conquer Rome’s Greek provinces. Leadership of the army sent to conquer him was disputed between Lucius Cornelius Sulla and Gaius Marius, with Sulla originally being in command and then successfully resisting an attempt by the Senate to replace him with Marius. This led to Sulla marching on Rome and seizing the city by force, which in turn led to a bloody conquest of Rome by Marius as soon as Sulla had left for Greece to defend the border. Marius instituted a reign of terror where his political opponents in the city were executed, a reign that was ended by his death of natural causes (he was 71 years old) as Sulla marched back towards the city. Still it was not until 82 BCE that Sulla reconquered the city, and in his purges there were at least fifteen hundred official victims (and maybe another seven thousand unofficial ones). [1] It was during this period that the first infamous incident of Catiline’s life occurred.

Catiline had kept his head down during the Marian regime, but his brother-in-law Marcus Marius Gratidianus had been a prominent subordinate under Marius, and was one of the candidates to succeed him after his death. As a result when Sulla had won the battle on the plains and begun his march on the city, it was certain that Gratidianus would be one of those executed. Catiline and Quintus Lutatius Catulus, the son of a man who had been prosecuted by Gratidianus and died as a result, conspired to preempt that execution by murdering him – Catalus for revenge, and Catiline to avoid being dragged down with him.

The killing was witnessed by Cicero, the young cousin of Gratidianus and future enemy of Catiline. He reported that Catiline cut off Gratidianus’ head and carried it through the city to give it to Sulla for display alongside the heads of his other enemies. Other accounts add the detail that Gratidianus was tortured before he was killed, either by being scourged or by having his limbs broken. It is worth noting, though, that few of these accounts mention Catiline, and so Cicero may have exaggerated his role in affairs. What is notable though is that Catiline escaped the purges despite his tie to Gratidianus. His wife and son did lose their lives in the turmoil, and Catiline was later blamed for organising their murders to leave him free to remarry into the new regime.

Catiline’s success in the new regime can be measured by the pushback against it, and in 73 BCE that pushback took a potentially deadly turn. He was accused of committing adultery, but not with just any woman. Catiline was charged with sleeping with a woman named Fabia, who was a Vestal Virgin. The Virgins were the priestesses of Vesta, the goddess of the hearth. In a society that respected its institutions more the older they were, the Virgins were one of the oldest. They had been founded back in the days when Rome still had kings, and they had become a powerful force in Rome’s religious and political life. But that power came at a cost. As their name suggests, the Vestal Virgins were sworn to chastity. Breaking that vow resulted in the man involved being whipped to death in the forum, while the Vestal (who was still considered sacred) was buried alive with a few days of food. Thus she was killed without anyone being responsible for killing her.

Less than a dozen women were ever convicted of breaking their Vestal vows, and it was often the case that it happened at a time when Rome was suffering misfortune. This allowed the superstitious Romans to blame their ill-luck on the priestess’ misconduct. This was such a time, and so both Catiline and Fabia were both in genuine peril. Catiline may have been guilty, but it’s far more likely that it was engineered by his political opponents. However Catiline was not without resources of his own. Catalus, the man who may have joined him in killing Gratidianus, was now one of the leaders of the Optimates. This was the traditionalist faction within the Senate, who were currently on the ascendant after Sulla’s brutal reassertion of the Senate’s supremacy. With Catalus’ weight thrown behind him, Catiline (and Fabia) were exonerated.

In 68 BCE Catiline became a praetor. This was an appointed position, roughly equivalent to being a chief magistrate. The post was a prestigious one, and was traditionally followed by a two-year term as the governor of a Roman colony. Catiline went to be governor of the Roman province of Africa, after which the continent is now named. Roman Africa was basically what had once been Carthage, before the Romans had destroyed it. The lands of the only empire to rival Rome were rich, and as was usual for Roman governors Catiline took full advantage of the opportunities the post offered to enrich himself. In fact, he may have taken too much of an advantage. When he returned to Rome in 65 BCE and put himself forward as a candidate for consul, he was blocked by allegations of abuses during his time as governor. Once again he went on trial, and once again he was found innocent. His enemies later suggested this had been due to bribery, but in truth it was unlikely the court would have convicted a good Roman Patrician for some crime in the provinces as that would set a dangerous precedent of accountability. Besides, he might even have been innocent. The accusation might just have been intended to derail his consular run, and if so it succeeded.

Catiline might have been grateful not to be involved in the mess that the consular elections of 65 BCE became. Publius Autronius Paetus and Publius Cornelius Sulla (the latter a nephew of the infamous Sulla) were both elected as consul. However they were controversially blocked from taking office under a law passed two years earlier to prevent electoral corruption. Instead they were replaced by two of the other candidates. It was later alleged that they conspired with Catiline (who was upset at being excluded from the election) to murder those other two candidates and declare themselves consuls by force, but if they did consider it then they never acted on the plan.

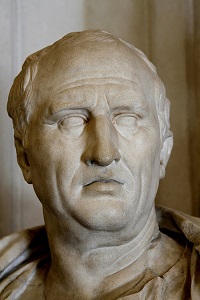

Once he had been cleared of the charges arising from his governership Catiline once again put himself forward for consul, this time in the elections of 64 BCE to take over as consul the following year. By some accounts Cicero hoped that Catiline would run alongside him, with each supporting the other in order to take both seats. [2] However Cicero’s reformist platform was opposed by the newly emerging power duo of Julius Caesar and Crassus. Caesar and Crassus sponsored Catiline and another candidate, Gaius Antonius Hybrida. They threw money around like water, leading their opponents in the Senate to propose a new law to limit campaign spending. When this law was vetoed by one of the tribunes (who was part of the Caesar-Crassus party) Cicero gave an impassioned speech in the senate to denounce this undemocratic behaviour. The speech doesn’t survive, but it must have been an amazing one. Cicero, who was originally an outside candidate due to his rank as a novus homo – somebody whose family had never held a seat in the Senate before, immediately became the favoured candidate of the Senate. As a result of their support, Cicero managed to win the election, with second place going to Gaius Antonius Hybrida. Catiline came third by a narrow margin, but it was enough to deny him his life’s ambition of becoming consul.

After this failure came another grave danger. Marcus Porcius Cato Uticensis, better known as Cato the Younger, had become quaestor. This was a junior magisterial post with responsibility for finance and taxation normally seen as simply a stepping stone to greater things. Cato was smart enough to see the real power this gave him though, especially given the illegal profits many Romans had made under Sulla’s purges. Cato was a Stoic and was almost fanatically devoted to seeing justice done, and so he went after them even though many were now powerful and influential men. First he went after them for financial misconduct, and then those who had been involved in the deaths of the innocent were prosecuted for murder. This led to a great many trials, and Catiline was one of those accused on both counts. Though he was found innocent, the court case destroyed what remained of his political capital.

Catiline stood for election a second time as consul in 63 BCE, but he knew he faced an uphill struggle. His last campaign had left him without allies in the senate, so he took what was always a last resort in Roman politics. He went to the people. The wars that had taken place in Italy over the last twenty years (both the civil wars and the slave revolt led by Spartacus) had left the country devastated and a lot of people deeply impoverished. This had been taken advantage of by those already wealthy to further enrich themselves through money-lending, which left many both endebted and deeply resenting it. Catiline’s proposal was known as tabula novae – the clean slate. This was simply a wiping out of all debts, a radical policy that won him few friends in the nobility but which appealed to the masses. With Rome’s limited suffrage this wasn’t a policy that would win Catiline the election. That was okay with him though. He had a different, and more violent, route to power in mind.

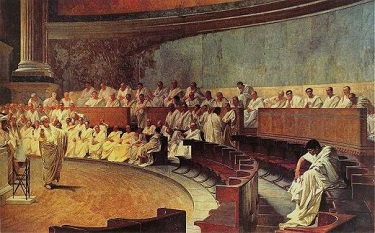

Catiline’s conspiracy was formed of those nobles who, like him, had lost their support in the senate and their chance at advancement. Rather than fade into obscurity they chose to risk it all on one last grab at power. Catiline sent a former centurion named Gaius Manlius to Etruria to raise an army. This was the area which had rebelled against Rome when Catiline came of age, and which had been denied the rights of citizenship as a result. It was fertile ground for Manlius to raise a large army ready to march on the capital. Meanwhile in Rome Catiline and his friends plotted to kill Cicero, who was seen as the man most likely to rally the people against them. This backfired in a major way when word of the plot reached Cicero. He immediately hired bodyguards and denounced Catiline to the Senate. Catiline appeared in the Senate to speak against these accusations, and may even have convinced them of his good intent. No official action was taken against him, but Cicero was now protected.

Inevitably Catiline lost the election, and he pretended to take this result with good grace (while still preaching his doctrine of tabula novae to the people). However he began sending messages to Manlius and preparing for a coup. The massacre of potential opponents within Rome was planned for the 28th, but like many such conspiracies before and since it was undone by one of its own. A conspirator sent a letter to Crassus, telling him that he should flee the city. (Or else Crassus learned of the plot and forged the letter, which would not have been unlike him.) He took the letter to Cicero, and Cicero took it to the Senate. Cicero was granted the authority to investigate the conspiracy and to secure the capital, though Catiline still remained free in the absence of evidence against him.

On the morning of the 7th November two of the conspirators made a visit to the house of Cicero planning to assassinate him, but he had been forewarned and it was guarded against them. The following day he delivered a speech in the Senate denouncing Catiline. Catiline was there, but as the speech continued the other senators moved away from him leaving him alone. Catiline responded with a firebreathing speech of his own, reminding them of his noble heritage (in contrast to Cicero). In contrast to this apparent defiance, when he left the Senate he almost immediately fled the city (under the guise of “going into voluntary exile”). Before he left, he gave the ringleaders left in the city the order to eliminate Cicero by whatever means they could.

Cicero had won a victory, but it came at a cost. Now he had no visible enemy. Luckily for him, the five conspirators were about to make a fatal miscalculation. Envoys from a Gaulish subject tribe (the Allobroges) had recently come to Rome to protest against misconduct by their Roman governor. The conspirators approached them and offered to aid them if they supported the conspiracy. The Allobroges played along until they had learned all the details of the conspiracy, and then betrayed them to Cicero. He arrested the conspirators in a clean sweep, breaking the back of the conspiracy. After a fierce debate in the Senate (where Caesar, the new Praetor, argued that the rule of law had to be observed) it was decided that the men should be put to death without trial. The sentence was carried out immediately.

Cicero was immediately hailed as the saviour of Rome, though his enemies lost no time in using his having “executed Roman citizens without trial” against him. This was only halted when the Senate passed a motion absolving those who had acted against the conspiracy of misconduct. The people were on Cicero’s side throughout though, and he was considered thereafter the saviour of Rome. There was still the matter of the army north of the city to consider, of course, but that became much less of an issue when news reached it of the events in Rome. Fully three-quarters of Catiline’s forces deserted him, and he knew that the rest were hopelessly outnumbered. He marched north in the hopes of escaping to Gaul, but he found the passes through the Alps blocked by Roman loyalists. His forces made a last stand near Pistoria. When Catiline saw the day was lost he charged headlong into the enemy forces, preferring to be killed by them than be captured alive. He was found on the battlefield mortally wounded but surrounded by dead enemies, and died “a most glorious death, had he thus fallen for his country.”

After the threat of his conspiracy had passed, there was a certain amount of respect for Catiline among the common people. It was in reaction against this that many of the contemporary histories (written by upper-class senators) describe him in extremely poor terms. Gaius Sallustius Crispus, known as Sallust, is one such historian. His book about “the Catiline conspiracy” is one of the few books from this time that has survived completely intact, and so his portrait of Catiline as a depraved power-hungry maniac (lining up as it does with Cicero’s surviving speeches) was the most popular view among historians for centuries. Folk legends portraying him as a revolutionary of the people, which persisted up until medieval times, are probably equally biased. The truth is most probably that he was a man who, like many Romans, had an overwhelming ambition to succeed. But the difference was that Catiline was not prepared to accept failure, and that when his legitimate path to the consulship failed he was prepared to go to any lengths to bring glory to his family and his name. Of such ambitions are true villains made.

Images via wikimedia except where stated.

[1] The property of those purged was sold off cheaply by the state, something which drove many who were innocent of any charge to be accused and killed simply because they were rich.

[2] This type of subversion of any electoral system designed to produce a diversity of opinion has a long history, though the Romans rarely reached the height of modern party systems and machine politics.