Alexander Pearce, the Tasmanian Cannibal

Though it’s true that Australia was largely settled by convicts it was far from a lawless place in the early 19th century during the heyday of “transportation”. The sentence of transportation was a compromise by a British government moving away from the old “Bloody Code” that saw people hanged for stealing anything worth more than a shilling. [1] They didn’t want to go to the expense of building prisons, so instead they settled on sending these people out to the fringes of the Empire, wild unsettled lands where they might be able to “civilise” things through forced labour. So throughout the 18th and 19th century men, women and children were “transported” for crimes like stealing cheese, carrying a burglar’s tools, bigamy, and pretending to sell somebody wine. Some made their sentence into an opportunity, and built a new better life on the other side of the world. Most served their time in the colonies quietly, and then returned home when their sentence was served. Some refused to abide though, and found themselves sentenced to a prison within the prison. One such was Alexander Pearce.

Alexander Pearce (sometimes Pierce, as spelling was still an approximate art in those days) was born in County Monaghan sometime in 1790. Very little is known of his early life except that he was poor. He mostly found work as a farm labourer, and probably supplemented his income with petty criminal activities. In 1819 those activities caught up with him when he was convicted by a court in Armagh for stealing six pairs of shoes. The 29-year old Pearce was sentenced to seven years of transportation, loaded onto a ship, and then taken halfway around the world to the island of Tasmania.

At the time Tasmania was called “Van Diemen’s Land”, after the Dutch governor who had sent the expedition that found it. [2] Up until 1800 convicts had been sent to New South Wales on the Australian mainland, but as that transitioned into a more standard colony the residents objected to the constant influx of convicted criminals. So they had been diverted to Tasmania. Given the non-violent nature of his crime, Pearce was probably assigned work as a farm labourer; not that different from what he had been doing back in Ireland. Also not so different was Pearce’s tendency towards side activities. He committed various offenses, starting with stealing ducks and turkeys and then working his way up to forging a work order. This was a serious enough offense that when it was discovered in May of 1822 he “absconded” (the official term for when a convict abandoned their sentence). A £10 reward was offered for his arrest, with the Hobart Town Gazette giving the following description:

A. Pearce, a convict, (No. 102) charged with divers misdemeanours, is 5ft. 3¼ ins. high, brown hair, hazel eyes, aged 30 years, a labourer, tried at Armagh in 1819, sentenced 7 years, arrived in this colony in the Castle Forbes in 1820, born in the county of Monaghan, and is pock-pitted.

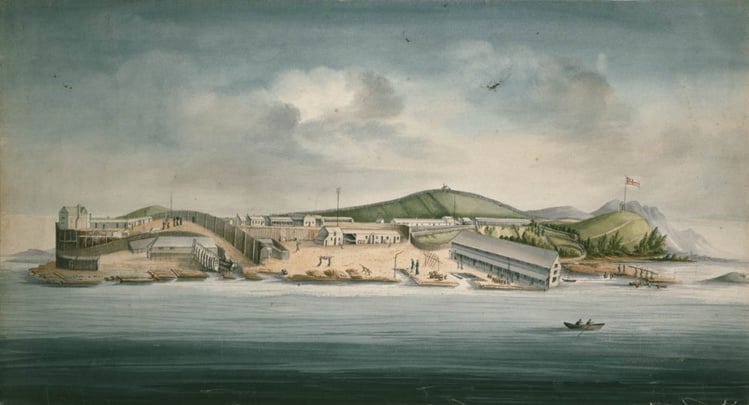

Pearce was recaptured, but since he had violated the trust placed in him he was not sent back to work as a labourer. Instead he was sent to Macquarie Harbour, on the west coast of the island. This was considered the ideal place to hold recalcitrant convicts, as it was surrounded by waters so treacherous that even ships approached it with great care. (In fact, more than a few convicts never even made to to the prison because their ships strayed from the narrow sea-passage and were wrecked.) On the land side of the harbour it was surrounded by mountainous wilderness, with hundreds of miles of travel to the main settlements on the other side of the island.) Overall, it was considered entirely escape-proof. So naturally less than two months after he arrived on the island Alexander Pearce tried to escape.

Pearce was part of a work gang with seven other men cutting down trees on the edge of the settlement on the 20th September when they made their escape attempt. The ringleader was Robert Greenhill, a former sailor who came up with a plan to steal a whaleboat and head out to try and reach either the mainland, China, or one of the Pacific Islands. Their exact destination never became an issue because the boat was too heavily defended for them to steal it. Before doing so though they had overpowered their overseer, so they were already committed to some form of escape. So they headed off into the impassable wilderness with the idea that anything was better than Macquarrie Harbour.

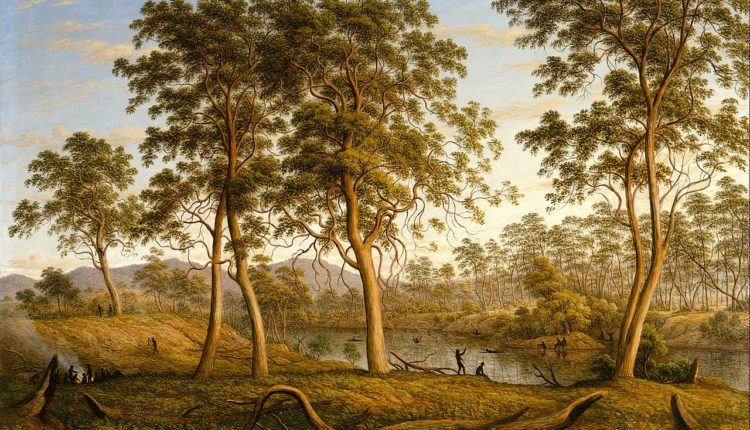

Though Greenhill (as a sailor and used to navigating) took the lead, none of the escapees were used to living outdoors. (His leadership also may have come from him commandeering the overseer’s axe when they fled.) Even if they had been practiced survival experts, this wilderness was so bleak that there was almost no life to be found. After eight days they were starving and desperate. That was when the cannibalism began.

Pearce claimed that the reason they chose to kill Alexander Dalton was because back in the prison he had been one of the volunteers who issued floggings to those who broke the rules. Floggings were a regular occurrence in Macquarrie Harbour; the following year in 1823 it’s estimated that 9,100 lashes were given in total to the prisoner population. Men who volunteered for that type of duty were generally despised, so the only question could be if they’d decided on cannibalism before or after one of them murdered Dalton. Either way the deed was done, and the seven starving survivors feasted.

The next morning there were only five of them; Edward Brown and William Kennerly [3] had decided that some things were worse than Macquarrie Harbour so they fled under cover of darkness. They did manage to find their way back, but they both died within a few days of returning. Officially this was of “exhaustion”, unofficially that might have been helped along by the rough discipline meted out on escapees like them. If it was the latter, it wasn’t recorded.

There are some inconsistencies in Pearce’s accounts of the escape, which we are relying on for this. In some accounts he says that it was actually Thomas Bodenham who they killed and ate after he lost in a drawing of lots; and Dalton fled the camp along with Kennerly and Brown. If that’s true then Dalton didn’t make it back to Macquarrie Harbour with them, but if he was the first victim then Bodenham was the second. That left Pearce, Greenhill, Matthew Travers and John Mather trudging through the wilderness. Mather was the next to go, five weeks into their journey. That left three men, and left things looking bleak for Alexander Pearce. Because Travers was close friends with Robert Greenhill. And Greenhill was the one with the axe.

Things weren’t as bad as they could have been, as by now they had made it through the mountains and were in an area where they could scavenge some food. But this new terrain brought new dangers that the three men were ill-equipped to deal with. While drinking water from a creek Travers was bitten on the foot by a tiger snake. One of the deadliest snakes in Australia, the bite of the tiger snake invariably causes death unless treated with antivenom. This is where another inconsistency in Pearce’s story comes up, as he claimed that he and Greenhill brought Travers along with them for five days before mercy-killing him in his sleep. If it was a tiger snake that bit him, then he would not have survived that long. However it happened though, Travers died and the two survivors fed.

After this, things got somewhat tense. Neither Greenhill nor Pearce trusted each other, and they did their best to avoid sleeping. After eight days Greenhill finally flagged, and Pearce took advantage. He managed to get the axe without waking him, and then killed him with a single blow to the head. That left Alexander Pearce as the sole survivor of the eight men who had escaped McQuarrie Harbour less than two months earlier.

Somehow Pearce managed to make it the rest of the way to the edges of the Tasmanian colonies on the east coast. He knew he had made it when he found sheep grazing in field. And in an unlikely coincidence, the first person he met from those colonies was an old friend who was working as a shepherd for those sheep, and who found him eating one of them that he had killed. The friend pointed him towards a local gang of bushrangers, escaped convicts like him who survived by rustling sheep. Pearce joined the gang, but unfortunately for him a month and a half later they were all captured by the Tasmanian authorities.

The examining magistrate in Pearce’s case was the Reverend Robert Knopwood. Knopwood had been born in England as the third son of a wealthy family who became an Anglican priest at the age of 26. He inherited a fortune when his elder siblings died before his parents, and then lost it all gambling beyond his means when he fell in with the Prince Regent’s crowd. Forced to find employment he took a post as a navy chaplain, and then became the official chaplain and later magistrate for the town of Hobart. He served in that post for twenty years, and his diaries are one of the best primary sources for early conditions in Tasmania. Pearce’s case must have been one of the last ones he ever heard before his retirement.

The appearance of a convict who should have been in MacQuarrie Harbour caused some consternation, and Pearce was pressed to give an account of how he had made it across the island. Perhaps out of guilt, he made a full confession: the details of their escape, how they had turned on each other, and the multiple instances of cannibalism he had committed. In fact his confession was so frank and shocking (even by the rough frontier standards) that Knopwood didn’t believe him. He decided that Pearce had invented this story in order to cover for the others who had escaped with him, and that some of them must still be out there as bushrangers. So instead of the death sentence he expected, Pearce was sent right back to MacQuarrie Harbour.

Because he had escaped once, Pearce was “ironed”: made to wear restrictive iron shackles on his legs so that he could not escape again. This did more than restrain him, though. It also marked him out as a symbol to his fellow inmates that escape was possible. One man who was entranced by that promise was Thomas Cox. Cox was an Englishman who had been only seventeen years old when he was sent to Tasmania. His crime must have been a severe one, since while most were only transported for seven years Cox was sent “for the term of his natural life”. This was reflected in his conduct in Tasmania, as he quickly became an absconder. When caught he managed to break out of prison, but he was caught again and sent to MacQuarrie Harbour.

Despite his confession it’s likely that Pearce hadn’t mentioned his cannibalism to the other prisoners. Even if there were rumours Cox would have been desperate enough to ignore them. He was facing the rest of his life in MacQuarrie Harbour, a place as close to hell on earth as could be imagined. He had a plan, and he had equipment – stolen fishhooks, a piece of flint to start a fire, and scorched rags to use for tinder. Cox spent months trying to persuade Pearce to escape with him. Eventually, after he had been flogged for stealing a shirt, Pearce cracked. While they were north up the coast from the harbour on a foraging expedition they bolted into the wilderness.

Eleven days later, Pearce was recaptured at the mouth of the King River, after he lit a signal fire and surrendered to a passing boat. He told the pilot (who recognised him) that Cox had drowned in the river. When they searched him they found a “piece of flesh” in his pocket. Pearce said that he had cut it from Cox’s corpse to prove that he was dead. Then he changed his story and admitted that he had killed Cox. The next day Pearce was taken out retrieve Cox’s body. What they found was horror. Cox’s head and hands had been removed from his body, and he had been disemboweled (the first step in turning a body into meat). The flesh had been carved from his flanks, legs and arms. There was a bloody axe nearby, which Pearce admitted was the murder weapon.

Back at the prison, Pearce made a confession. He told them that he and Cox had planned to go round the coast to the north to reach the settlement of Port Dalrymple, since Pearce knew how barren the mountains were. When they reached the King River though, they had hit a problem. One thing Cox hadn’t told Pearce was that he didn’t know how to swim. When Pearce found this out he lost his temper and killed Cox with an axe. (They had stolen the axe in order to break off Pearce’s irons.) Then Pearce had butchered the corpse, but had been overcome with self-loathing and thrown the meat into the river before eating it. He had kept a piece in his pocket to prove his crime, then signaled the boat.

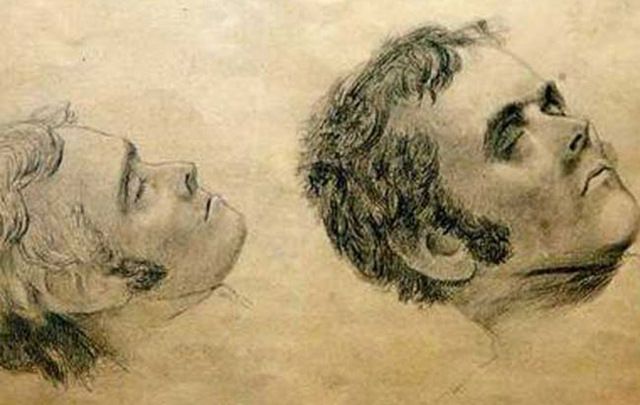

Pearce said at that time that he was ready to die for his crime, but when the case went to trial he had changed his mind. Charged with murder, he pleaded Not Guilty. The grounds for his defense was that he had killed Cox during an argument, and was only guilty of manslaughter. By now his confession to Knopwood was well enough known that the jury had to be told by the judge to disregard it, but it made no difference to their verdict. They found Pearce guilty of murder, and he was executed a month later. Before he died he made one final confession, which differed in details but was largely identical in content to his previous ones. His last words were recorded as being:

Man’s flesh is delicious. It tastes far better than fish or pork.

The story of Alexander Pearce was a part of the inspiration of For The Term Of His Natural Life, a novel by Marcus Clarke published in 1874 that became the most famous story about the Tasmanian convicts. And it inspired songs and films, including The Last Confession of Alexander Pearce which was a joint Irish-Australian production that won awards on both sides of the world. Though Pearce never left Tasmania alive, his legend has escaped on his behalf. And he did eventually make it out himself…in a way.

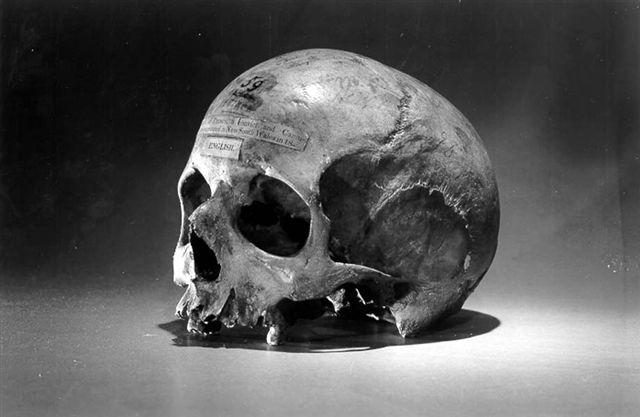

The judge had ordered that Alexander Pearce’s body be given to science for dissection after his death, an unusual provision that might have been prompted by his desecration of the corpses of his victims. His skull ended up as part of the collection of Samuel Morton; an American scientist who was convinced that the skulls of criminals showed abnormalities. When Morton died he bequeathed his collection to the University of Philadelphia, where it’s still on display. And that’s how at least one part of Alexander Pearce ended up escaping from that island prison at last.

Images via wikimedia except where stated.

[1] Or for other crimes designed to keep the poor in their place, such as “stealing from a rabbit warren” (ie poaching on a nobleman’s estate while starving) or “concealing a stillborn child” (ie being even vaguely suspected of having an abortion).

[2] It was renamed Tasmania, after the explorer who found it, because the people living on the island thought the original name was permanently tainted by association with convicts.

[3] His surname is given as “Cornelius” and not “Kennerly” in the newspaper accounts at the time, but Kennerly is the more accepted version based on the records.