A legend to India and a Monster to Britain – Lakshmi Bai, the Rani of Jhansi

The girl who who would become Lakshmi Bai, hero to some and villain to others, was born between 1830 and 1835 in Varanasi, the oldest of Indian cities and the religious capital of the subcontinent. Her birth-name was Manikarnika, one of the names for the holy Ganges river which flowed past the city, but she was known as Manu. Her parents were Karhade Brahmins, members of one of the higher-status of the Indian castes. In keeping with this status, her father worked as a court official for Peshwa Baji Rao II. Baji Rao had been the last leader of the Marathra Empire, the only power in India that had held the British in check until their defeat in 1818. Under the terms of the treaty he had been pensioned off in the tiny town of Bithoor. Manu’s mother died when she was only four, and so she was raised alongside the Peshwa’s sons, receiving a far more masculine education than a girl of her caste normally would. One of her foster-brothers was a young man named Dhondu Pant, who like Manu grew up on his father’s tales of freedom, and like her found much there to ponder.

When Manu was thirteen years old her father moved to Jhansi, an independent city-state held under dominion of the British ever since its ruler had foreseen the fate of his Marathra overlords and changed allegiances. Young Manu caught the eye of her father’s master, the Maharajah Gangadhar Rao, and the following year she married the widowed ruler, who was in his forties at the time. [1] At this point she took the name of Lakshmi Bai, and the title of Rani (short for Maharani, or Queen) of Jhansi. The Maharajah’s previous wife had died without producing an heir, and so when the Rani gave birth to a son in 1851, there were celebrations throughout the kingdom. Unfortunately the child died only three months later. This was a severe blow to the Maharajah, and though the couple adopted his cousin’s son (who was given the name of Damodar Rao) as his son and heir, the Maharajah never truly recovered from the death of his only biological child. He died in 1853, and his death immediately drew the opportunism of the British East India Company.

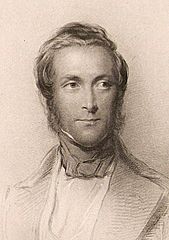

At the time the East India Company was Britain’s proxy in India, effectively ruling over the British-controlled territories on behalf of the crown. The head of the company was Governor-General Lord Dalhousie, a Scottish Earl who had a strong belief in direct rule over Indian territories rather than rule by Indian subject kings. One of the tools he used to achieve this was the Doctrine of Lapse, a process by which he seized any territory held by a ruler under British dominion who died without a direct heir. Though under Indian law the adopted Damodar Rao had the same rights as any biological son, Dalhousie declared that he considered the line who had been granted Jhansi broken, and ordered the Rani and her son to vacate the palace and turn over rule to the EIC. Lakshmi Bai did her best to secure Damodar’s inheritance, even going so far as to consult a British solicitor and appeal directly to London herself, but her appeal was dismissed. Dalhousie got his direct rule, and the Rani was, like the Peshwa of Bithoor, pensioned off. She was permitted to remain in the city however, and raised Damodar in the shadow of the palace he could have ruled. She was a popular figure, seen going to the temple by the common people, and they considered her more their ruler than the East India Company officials who governed the city. Still, Lakshmi Bai considered the Company (and the Empire) too powerful and risky to rebel against, and she might have lived out her life in relative obscurity – if it hadn’t been for the grease on the cartridges of the Lee Enfield rifle.

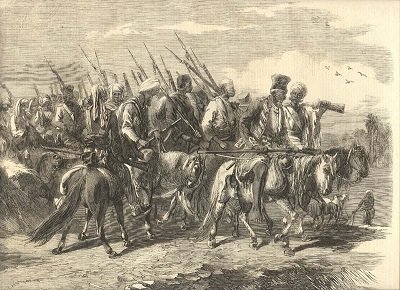

It might seem ridiculous that cartridge grease could spark a bloody revolt that would leave hundreds of thousands dead, but that in itself was part of the problem. At the time British rule in India was enforced by sepoys – native troops led by British officers. These troops were mostly a mixture of Hindus and Muslims, so when the rumour began to spread that the grease that came pre-applied to their rifle cartridges was made from a mixture of beef and pork fat, they reacted quite badly. [2] The cartridges were paper, and the end had to be bitten off before they could be used. If the rumour was true, this would be a violation of both religions’ dietary restrictions. The British, without any such restrictions, largely failed to appreciate how seriously this was taken by their troops. Tensions ran high, and the cartridges became the spark to the fuel of resentment of EIC behaviour in India. In April 1857 the refusal of 85 sepoys in Meerut to accept their greased cartridges, and their subsequent court martial, proved the final spur to an open and bloody revolt by the sepoys. So the Indian Rebellion (which the British at the time referred to as “the Indian Mutiny”) began.

The Rebellion reached Jhansi in June of 1857, when the rebellious soldiers of the 12th Bengal Infantry Regiment killed their British officers and seized the garrison. The EIC superintendent, Captain Alexander Skene, immediately had all the Christians in the city gather in the fort for protection. They left the fort two days later under a guarantee of safe conduct, supposedly from the Rani. As soon as they left, however, the rebels violated the safe conduct and killed them. After this, the sepoys left the city to head to Delhi to unite with other forces of rebels.

The local people looked to the Rani for guidance, and she swiftly organised her personal guard to bring order back to the city, sending a letter to Major Erskine, commander of the military forces in the area, to explain her actions. Her account agreed with what he had heard from other sources, and so he authorised her to take control of the city. Unfortunately for her, however, she fell victim to two powerful negative forces – opportunism, and tabloid journalism. The first came in the form of invading armies from Orchha and Datia, two neighbouring states which had not rebelled and which tried to take over Jhansi under the pretense of “restoring order”. The second was an outgrowth of the intense coverage the British press had been giving the Rebellion, going into lurid detail on every massacre and atrocity committed by the rebels (while glossing over the massacres and atrocities committed by the British troops and loyalists). [3] When news of the massacre at Jhansi reached them, and the subsequent takeover by the Rani, it took them no time to decide that she must have masterminded the whole affair. The exact truth is impossible to know – did she actually give that safe conduct? And if so, was it meant in good faith and broken by men she could not control? It hardly matters, regardless, since the important thing was that headlines about the “Demon Queen of Jhansi, Jezebel of India” sold newspapers. This soon became the prevailing British opinion, and so when she sent to ask for aid against the opportunistic invaders, she was ignored. She organised a local militia, however, and drove off the would be invaders. By August 1857 Jhansi was at peace once again.

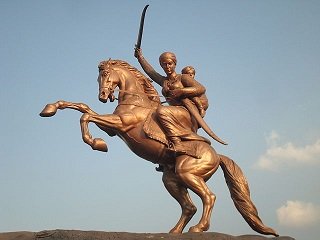

The growing promotion by the press of Lakshmi Bai as a hate figure meant the punitive action against her would come sooner or later, and in December 1857 a British force led by Major General Sir Hugh Rose set out for Jhansi. Though it seems that Lakshmi Bai had every intention of returning the city to British control Rose never gave her that option. He immediately besieged the city and produced an order for her arrest on the capital charge of treason. The Rani, who knew that she had little chance of avoiding execution in British hands, issued a defiant proclamation and the siege began on the 24th March. Lakshmi Bai sent a message to her former foster-brother Dhondu Pant, who was now the rebel leader Nana Sahib, and he sent a force of 20,000 men under the command of his general Tatya Tope. However the relief force was defeated by the British, and by the 2nd April they had breached the walls and entered the city. The British forces massacred any inhabitants of Jhansi they met, and it is estimated that 50,000 people – the majority of the city’s population – were killed in the fighting. The Rani’s father was captured and executed. Lakshmi Bai herself managed to escape on horseback with her young son tied to her back. Legend had it that she jumped her horse from the walls of the fort to the ground below, with the animal dying but breaking her fall. Another story was that Jhalkabari, the wife of one of Lakshmi Bai’s bodyguards who had joined the militia and who bore a strong resemblance to the queen, fought on the front lines disguised as the queen in order to sow confusion and aid her escape, before being captured by the British and executed. [4] The queen did manage to escape, with at least a core of her forces, and retreat from the doomed city.

The Rani managed to make it to the fortress of Kalpi, where she met up with her foster brother Nana Sahib, along with Tatya Tope. This was both a fortune and a misfortune, as Nana Sahib had become for the British the face of the rebellion (after his massacre of a group of British civilian prisoners the previous summer), and so his location was bound to come under constant attack. The rebel forces clashed with the British several times (with the Rani, in male warrior’s attire, leading her troops into battle). Eventually they were driven from the city and forced to retreat towards Gwalior, a province whose leader had remained loyal to the British. Though the Maharajah tried to deny them entry, his troops rebelled and forced him to flee. The British forces continued to pursue them, and on the 16th of June the Rani led a force to try to hold them back. During the ensuing battle she was shot off her horse and died. She asked her servants to cremate her body to prevent it falling into British hands, and they tried to do this on the battlefield but were driven off before they could complete the funeral. General Rose, who described her as “remarkable for her bravery, cleverness, and perseverance…the most dangerous of all the rebel leaders”, arranged for her burial to be completed with all due ceremony. Her grave in Gwalior stands to this day.

Despite Rose’s opinions, the British press were jubilant at the death of the woman they had built up as a monstrous figure. By the end of the year the Rebellion was crushed, though it spelt the end for the East India Company. The British government assumed direct control of India for the next century. Naturally the Indian nationalist movement in the 20th century looked to these earlier rebels for heroes, and Lakshmi Bai, the woman driven into rebellion, became the greatest of these. When the Japanese attempted to raise up a new Indian Rebellion in 1942 an all-female unit of the rebel army was named after Lakshmi Bai. Songs in praise of her bravery and prowess in battle soon made her into a legend, and now statues of her on horseback with Damodar on her back [5] can be found all over India. Films, television series, and even an appearance in George MacDonald Fraser’s Flashman series all ensure that the Warrior Queen of Jhansi, though defeated, lives on.

Images via Wikimedia.

[1] The uncertainty of Lakshmi Bai’s birth year mean that the date of her marriage is also uncertain – it was between 1842 and 1849, at any rate.

[2] The cartridges were actually greased with a mixture of beeswax and vegetable oil, but the sepoys did not believe assurances of this. They already viewed British reforms such as outlawing child marriage and suttee (the ritual burning of widows on their husbands funeral pyres) as attacks on their faith.

[3] This is not to downplay the actions of the rebels or the British, but simply to point out that neither side had clean hands in the conflict.

[4] Jhalkabari has in recent years become a symbol of heroism and pride for the Dalit in North India, with the date of her execution by the British celebrated as “Martyr’s Day”.

[5] Damodar, by the way, survived the rebellion and wound up accepting a British pension (and his life) in exchange for giving up all claim to Jhansi.