“Ascend thy Horse Naked” | Lady Godiva and the Raunchy Rashomon Effect

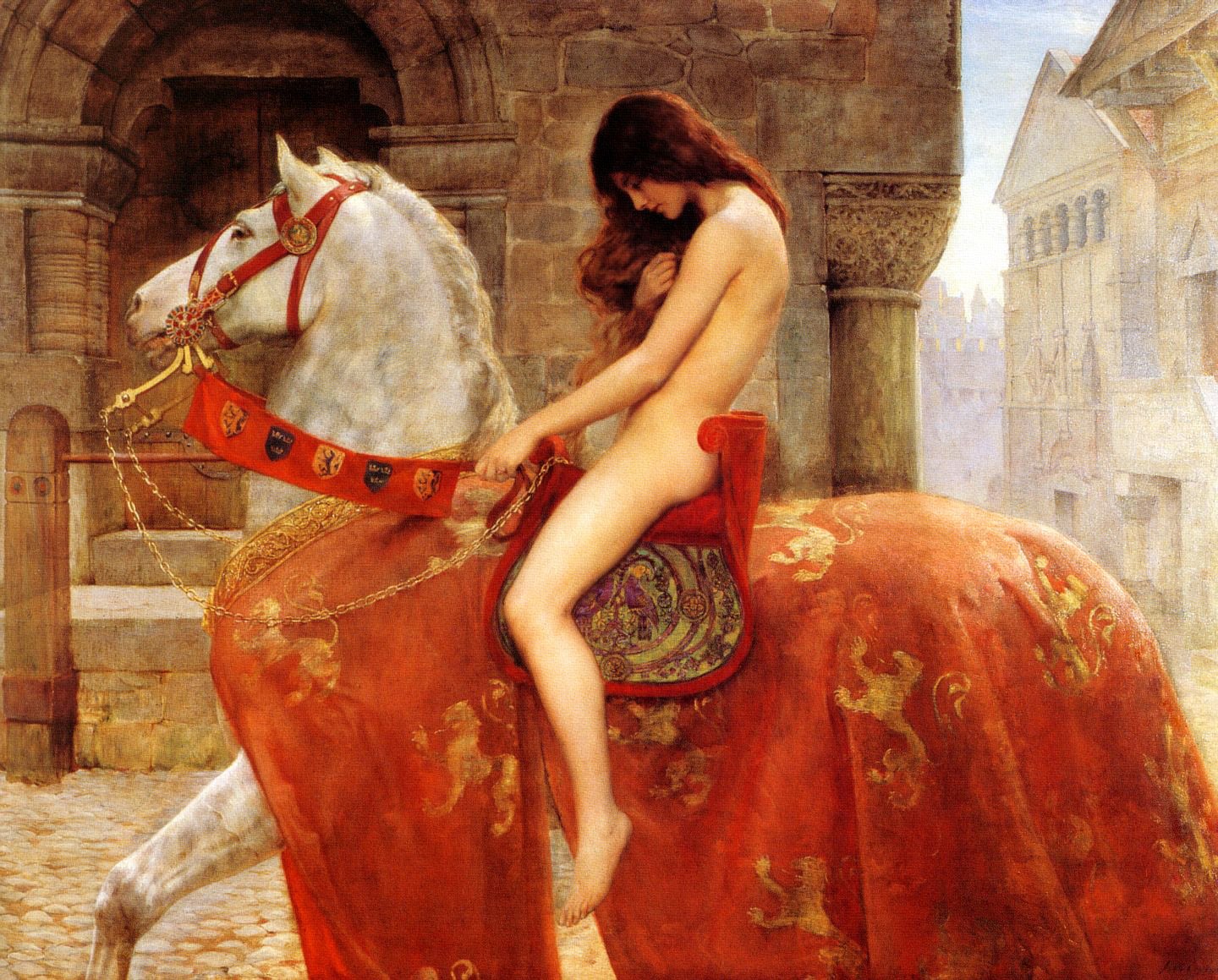

In the centre of Coventry, a midlands city in England, there is a statue of a woman astride a horse, her head bowed, unclothed except for her long hair. Across the road, at the top of a slate grey brick clock tower every hour, on the hour, a smaller version of the woman on the horse circles underneath the caricature of a man with binoculars leering over her. They are Lady Godiva and Peeping Tom.

Every place has its own mythology and for Coventry the Lady Godiva story is a vital part of the city’s historical consciousness. It is a story that every school child learns and every migrant to the city becomes acquainted with. However, how much does the story fit with the historical facts and why has this story lived so long in the city’s memory?

Growing up in Coventry, this is the version of the story I was told: Lady Godiva was the wife of Earl Leofric, Lord of Mercia in the eleventh century. Leofric, a very powerful and influential man enforced heavy taxes on his people. Unable to pay Godiva pleaded their case, begging her husband to remove the taxes. He refused, eventually turning around and declaring that if she rode through the market place naked he would alleviate the citizen’s financial burden. Amazingly she took him up on this. One day, clothed only by her long hair, she rode through the market place in the middle of the day. Out of respect, every citizen shut themselves away and promised not to look, so as to preserve her modesty. One man however reneged on this. His name was Tom, and he took a peep, viewing her naked body. After the ride he was dragged into the market square and blinded by the angry citizens. Having completed her challenge Leofric removed the hated taxes, and Godiva became a local hero. This version however differs significantly from the facts.

Lady Godiva and her husband Earl Leofric were one of the last powerful noble families of the pre-Norman period in England. In old English, the name Godiva translates as Godgifu, meaning ‘gift of God’. She was independently powerful and wealthy. Leofric was one of the three great Earls of the eleventh century, responsible for ruling over the kingdom of Mercia. At the time Coventry was a very small place consisting of only 69 families and a monastery. Importantly Godiva actually owned Coventry outright and would have been responsible for setting taxes herself. This undermines the traditional story. Further the only two known taxes at the time were taxes on stabling horses and the Heregeld; a tax everyone had to pay to contribute towards upkeep of the king’s bodyguard. It was not possible for this tax to be removed and if Godiva choose to pay it on behalf of her citizens then there would have been no need for the naked horse ride.

[iframe id=”https://www.youtube.com/embed/6ut4nk231JE”]

The Anglo – Saxons had very different attitudes to nobility and gender compared with the incoming Normans. The first written records of the story date from the thirteenth century. Written from the Norman perspective it offered a less than glowing account of the previous Anglo – Saxon rulers, most of whom had been displaced after the invasion. This is significant as it helps to explain why the tale removes much of Godiva’s agency, independence and wealth. Similarly it is also at pains to paint Leofric in a negative light, as the heartless landlord oppressing his tenants. Arguably part of the reason for this is to show the Normans in a better light, rewriting history in their favour. It is worth noting at this juncture that divorce existed in Anglo – Saxon society and it was not unheard of for noble women to divorce their husbands if given reason to. If Leofric had indeed been so cold and cruel this is an option that Godiva could have availed upon.

References made to the couple during their lifetime and shortly after make no mention of the horse ride, and instead emphasise their wealth and piety. They were known for giving generously to religious houses, founding a Benedictine monastery in the town in 1043 (The monastery was later destroyed in the Reformation period). They also donated land to the monastery of Saint Mary in Worcester and Lady Godiva was known for donating her own jewellery, along with gold and silver, to churches and religious homes. On her death she left her own heavy gold chain, a sign of her status, to a local church, with the instruction that a prayer be said for each chain link. It appears that they were very generous with their wealth. Lady Godiva is the first woman to be recorded in the Domesday book, the great survey ordered by William the Conqueror to map and number the population, property and wealth of his new land. It was completed in 1087. Unusually she kept her wealth and land after his ascension even though William confiscated the land and property of most existing English nobles. It was noted that she had holdings in Leicester, Nottinghamshire and Warwickshire. Godiva must have been a powerful and popular woman to retain her property, especially as by this point she was a widow, Leofric having died in 1057. The date of Godiva’s death is unknown. Often cited as 1067 it has been argued to be anything between this date and 1086.

The story first dates from the thirteenth century when it was recorded by monk and collector of anecdotes Roger of Wendover in his Flores Historiarum. It is known that Wendover died in 1236, so the story must predate this. There are no surviving records of the story from before this. Historians place very little credibility in Wendover’s account. He was known to collect unusual stories and often stretched the truth beyond breaking point. This version differs from later versions. In Wendover’s story Godiva passed through the market attended by two knights. The people of Coventry were assembled but kept their eyes closed. Here is an extract from Flores Historiarum:

‘The Countess Godiva devoutly anxious to free the city of Coventry from a grievous and base thralldom often besought the Count, her husband, that he would for love of the Holy Trinity and the sacred Mother of God liberate it from such servitude. But he rebuked her for vainly demanding a thing so injurious to himself and forbade her to move further therein. Yet she, out of her womanly pertinacity, continued to press the matter insomuch that she obtained this answer from him: “Ascend,” he said, “thy horse naked and pass thus through the city from one end to the other in sight of the people and on thy return thou shalt obtain thy request.” Upon which she returned: “And should I be willing to do this, wilt thou give me leave?” “I will,” he responded. Then the Countess Godiva, beloved of God, ascended her horse, naked, loosing her long hair which clothed her entire body except her snow white legs, and having performed the journey, seen by none, returned with joy to her husband who, regarding it as a miracle, thereupon granted Coventry a Charter, confirming it with his seal’.

A different account came in the sixteenth century from Richard Grafton, M.P. for Coventry. The fiercely Protestant Grafton recorded a sanitised version of the story to better suit his, and his audiences, sensibilities. There are similarities though between this version and Wendover’s:

‘she returned to her Husbande from the place from whence she came, her honestie saued, her purpose obteyned, her wisdome much commended, and her husbands imagination vtterly disappointed. And shortly after her returne, when shee had arayed and apparelled her selfe in most comely and seemly manner, then shee shewed her selfe openly to the peuple of the Citie of Couentrie, to the great joy and maruellous reioysing of all the Citizens and inhabitants of the same, who by her had receyued so great a benefite’.

The introduction of the voyeur famously to be known as Peeping Tom is more recent, 17th century, addition. Here is an extract from the account of Humphrey Wanley (1672-1726):

‘In the Forenoone all householders were Commanded to keep in their Families shutting their doores & Windows close whilest the Duchess performed this good deed, which done she rode naked through the midst of the Towne, without any other Coverture save only her hair. But about the midst of the Citty her horse neighed, whereat one desirous to see the strange Case lett downe a Window, & looked out, for which fact, or for that the horse did neigh, as the cause thereof. Though all the Towne were Franchised, yet horses were not toll-free to this day’.

Alfred, Lord Tennyson later further romanticised the story with his poem Godiva, written in 1840 and published in 1842. The lengthy poem emphasised Godiva’s virtues, particularly her chastity, for his Victorian audience.

‘… loathed to see them overtax’d; but she

Did more, and underwent, and overcame,

The woman of a thousand summers back,

Godiva, wife to that grim Earl, who ruled

In Coventry: for when he laid a tax

Upon his town, and all the mothers brought

Their children, clamouring, “If we pay, we starve!”

She sought her lord, and found him

…

‘“Then she rode back, clothed on with chasity;

And one low churl, compact of thankless earth,

The fatal byword of all years to come,

Boring a little auger-hole in fear,

Peep’d – but his eyes, before they had their will,

Were shrivell’d into darkness in his head,

And dropt before him.’

In these sources there are several themes that carry through the centuries. The first is the depiction of Lady Godiva herself. She is seen as being modest, chaste and brave. Further Leofric is also described in negative terms, as the cruel, cold husband and landlord that forces Godiva to do something that would have been seen as pretty extreme in order to help and protect the people of Coventry from his greed.

Over time historians have presented some possible explanations as to why this story has both been constructed and attached to Lady Godiva. For example pagan rituals were intertwined with Christianity at this time and the story bears some resemblance to fertility rituals. In the eleventh century Christianity and paganism were still closely interlinked. Following on from this it was also known for penitents to make a public procession to atone for their sins. The deeply pious Godiva may have made her way through the town before halting at the shrine of Saint Osburga, a nun who was killed several centuries earlier in a Viking attack. Alternatively the reference to nakedness could suggest she had removed her jewellery and other signs of her station. It is possible that stories and rituals of this manner occurred and over time became associated with Godiva, before passing into folk history.

Daniel Donoghue, author of one of the few works on Lady Godiva: Lady Godiva: A Literary History of the Legend has stated that ‘nobody knows quite why the legend was invented and attached to her name but it does seem to function as a kind of myth of origin for the town of Coventry’. It is telling that the statue was erected in 1949. Much of Coventry was destroyed in the 1940 Blitz and even more was wiped away by the town planners that rebuilt the city. It is significant that this statue has avoided all recent regeneration and rebuilding and remains the centrepiece for Coventry. Lady Godiva fits into the city image of personal sacrifice, martyrdom, of a victim rising from the flames that had become so important during the war years and helped to embed the story of Godiva in Coventry’s cultural consciousness.