Julie “La Maupin” d’Aubigny, swashbuckling opera singer

Mark Twain once wrote “Truth is stranger than fiction, but it is because Fiction is obliged to stick to possibilities; Truth isn’t.” Few things illustrate that quite like the life and career of Julie”La Maupin” d’Aubigny, the 18th century noble-born openly bisexual crossdressing swordfighter and opera singer. If Dumas had written her life story then the author of Three Musketeers would have been denounced as even more of a sensationalist than he already was. In fact, the most famous fictionalised account of her life (Mademoiselle de Maupin by Théophile Gautier) toned her down considerably and still wound up being banned in several countries. Given her tendency to embrace the drama of any situation, one feels that Julie would have approved.

Julie d’Aubigny was born in 1673 [1], the daughter of a minor noble named Gaston d’Aubigny. He was one of secretaries of the Comte d’Armagnac, the Grand Squire of France. D’Armagnac was responsible for the royal household and retinue, and Julie’s father’s particular responsibility was the training of the pages of the royal court. As she grew up, Julie received all the same training the pages received, though naturally she received it over a longer period, this may have left her one of the most well-educated teenagers in France at the time. She was somewhat a tomboy, and wore boy’s clothing to learn subjects like horseriding and fencing alongside the pages. Her father, who by all reports was no stranger to the seamier side of Paris, was determined that his daughter should be able to handle herself. At the age of 14, she caught the eye of the Comte d’Armagnac, and became his mistress. He arranged her marriage to a man named Maupin of St. Germain-en-Laye as a cover – a noble-born young girl like Julie could hardly be a public mistress, after all. Both the marriage and the affair barely lasted a year however, and Maupin was given a job out in the provinces – perhaps in the hope that he would take Julie with him.

Julie stayed in Paris however, and became known as something of a firebrand. She frequented the fencing schools, where she would compete against the masters – unconventional, but not really scandalous, as nobles did have a certain latitude. One of those masters, a man named Sérannes from Marseilles, became her lover. Unfortunately, in 1687 Sérannes killed a man in a duel, and duelling was (at the time) illegal. The Lieutenant-General of Police, Nicolas-Gabriel de La Reynie, was an avid enforcer of the anti-duelling laws, and d’Armagnac may have asked him to take a hard line with his ex-flame’s lover. He was forced to flee the city, and Julie decided to go with him. This meant leaving her noblewoman’s life of idle pleasure behind, but Julie left without looking back. The two became a travelling act, putting on fencing exhibitions. The novelty of a beautiful woman who could fight like a man made them quite popular, and when they arrived at Marseilles they had no difficulty finding work on the stage. The two sang as part of their performances, and Julie was encouraged to apply for formal training. This she did, finding that opera singing, like fencing, was something she had an immense natural talent for. She was trained by Pierre Gaultier, a friend of the great French composer Lully, and was given a job on stage at the prestigious Marseilles Opera House.

At some point during this Julie had broken up with Sérannes, and in 1690 she had her first (and most notorious) affair with another woman. The young blonde daughter of a local merchant (history has not recorded her name) became smitten with her, and Julie returned the affection. The girl’s parents, alarmed at this, had the young girl put into a convent in Avignon, but Julie was not to be deterred by that. She posed as a postulant nun and entered the convent herself, resuming the affair. When an elderly nun died, Julie stole the body and placed it in her lover’s bed, setting a fire to disguise the corpse. The two then fled. The affair only lasted three months before either Julie tired of the girl, or the girl tired of the privations of life on the road. Either way, she returned to her family in Marseilles. Once her tale was told, a tribunal was convened and Julie was convicted (in her absence) of body-snatching, kidnapping a nun, and arson against a convent. The sentence was death by burning. Julie had become a fugitive.

She made a living singing in inns, until in Poitiers she met an aging drunk named Marechal. He had been a professional singer in Paris, and he saw that Julie was wasting her talent. He trained her, and made her promise that she would take her place on the Paris stage. Once his alcoholism left him unable to teach her any more she set off north towards Paris, and on the road there in Villaperdue she met the man who was to become her greatest friend, Louis-Joseph d’Albert, son of the Duke of Luynes. The friendship started on a note that would be clichéd if it were in a novel – the two fought a duel. The reasons given for this vary (Julie was singing and d’Albert made an off-colour comment, Julie spilled wine on d’Albert in a tavern), but the results do not. D’Albert fancied himself a master swordsman, but nobody who knew his noble birth would ever give him a fair contest. He faced one of the best sword fighters of the age, with no reason to hold back her blade. The duel ended when she drove the point of her sword through his shoulder, and clean out the other side. Once again, here the stories diverge – one has her help him up to his room, where she discovers his noble birth and reveals her own, another has her only finding out after the fact when one of his friends called on her to apologise for d’Albert’s insulting words – but again, the result was the same. The two became lovers, beginning an on-again off-again affair that would continue in a casual fashion throughout their lives.

Parting from d’Albert with a pledge to see each other again, Julie continued through Rouen where she met another of the more important people in her life; Gabriel-Vincent Thévenard. Like her, Thévenard was a young singer headed to Paris to try his luck on the stage, and like her, he was a prodigiously talented singer. The two became compatriots and lovers, and set off to Paris together. Of course, Julie still had a grisly death sentence hanging over her head. Fortunately her former lover, the Comte d’Armagnac, was willing to intercede on her behalf, and he persuaded the King to have her death sentence annulled. Louis XIV seems to have found the tale somewhat amusing. Julie was free to enter the city, but unlike Thévenard (who was hired by the Paris Opera his first day in the city) she did not have instant success. Julie was undeterred, however. She befriended an elderly retired singer named Bouvard, who persuaded Jean Nicolas Francin, Master of the King’s Household and patron of the opera, to audition her once more. Julie’s voice was unusual for a female singer, but on the second hearing Francin recognised her talent. And just like that, she was in.

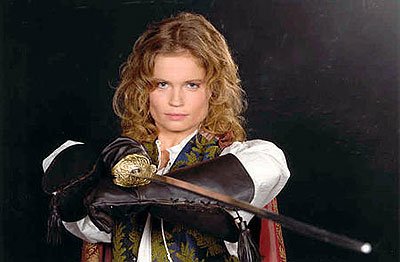

Julie would go on to become a fixture of the Paris Opera for the next fifteen years, under her married name of Madamoiselle de Maupin (known, in the tradition for singers of the time, as “La Maupin”). The famous French diarist Philippe de Courcillon wrote the she had “the most beautiful voice in the world”. Her appearance, too, attracted admiration – curly auburn hair, pale white skin, blue eyes, an attractive face and an athletic build. She also had a phenomenal memory – a huge advantage for one who had come to the opera relatively late in her life. Julie would often play goddesses and powerful women, with her debut as Pallas Athena setting the precedent for later roles as Minerva, Dido and Medea. At first she sang as a soprano, but later composers would create roles specifically for her more natural range, which was mezzo-soprano, halfway between soprano and contralto. The most famous of these was in 1701 as Clorinde in “Tancrede”, an opera written specifically for her to take the lead. The story is set during the Crusades, where Clorinde the Saracen warrior princess falls mutually in love with Tancrede, a young Crusader knight who captures her after a battle. Of course, this is complicated by Argant, the leader of the Saracens being in love with Clorinde, and Herminie, a princess of Antioch being in love with Tancrede. After Tancrede frees the Saracen prisoners (including Clorinde), Argant conspires with Isemenor, a magician who is in love with Herminie, to lure Tancrede to an enchanted forest and kill him. Herminie and Clorinde discover the plot however, and put their rivalry aside to foil it. Tragedy strikes in the end, however – on the battlefield, Tancrede kills a masked opponent that he thinks is Argant, only to discover too late that he has killed Clorinde, her loyalty to her people having forced her to fight him. The opera was the first in France to have a part for the lower female voice, and was a great success, and remained a fixture of the Paris stage for over sixty years. The composer, André Campra, would go on to write two more operas for Julie to take the lead in, “Iphigénie en Tauride” in 1704 and “Alcine” in 1705, though neither enjoyed the success of “Tancrede”.

Of course, Julie being Julie meant that success on the stage was often accompanied by scandal off it. She fell in love first with the lead singer of the opera, Marie Le Rochois, and then with another up and coming star named Francois Moreau, known as Fanchon. Julie was heartbroken when Fanchon refused her advances, and may even have attempted suicide. Her relationship with others of the company was sometimes less cordial. When a tenor at the opera named Desmuny, who had long been pestering Marie and Fanchon, decided to try his luck with her she rejected him. He replied with a vulgar epithet, and she swore vengeance. Donning her man’s garb, she waited for him in a public square and challenged him to a duel. He did not recognise her and refused, at which point she denounced him as a coward and attacked him with a cane, bearing off his watch and snuffbox. The next day he explained his bruises as having come from an attack by a gang of ruffians. Julie, dleighted by the opportunity to embarrass him further, declared “Duménil, you liar and base coward! It was I alone who defeated you. You were afraid to fight and so I gave you a sound thrashing. As proof, I return to you your miserable watch and snuff-box.”

The most famous of her scandals took place at a court ball hosted by the king’s brother in 1697. Julie attended in man’s costume, with a fencing foil on her hip. Here she made a beeline for a beautiful young noble lady, taking her out for several dances before kissing her in full view of the company. The girl’s three suitors took violent exception to this, and Julie offered to duel them in recompense. They retired out to the gardens where she took on all three and emerged victorious, but when she returned to the ball the King himself confronted her, referring to her as “the jade La Maupin” and reminding her of his decree against duels in Paris. Fortunately for Julie, his brother persuaded him to see the funny side and he issued a clarification that the decree only applied to the men of the city. La Maupin, as always, could do as she pleased.

Whether it was because of this royal attention or for other reasons, Julie took an extended holiday on the stage in Brussels. There she had an affair with Maximilian Emmanuel, the ruler of Bavaria. When the affair ended he sent the husband of his new mistress around with 40,000 livres to pay off Julie. Enraged, she threw the purse at his head and chased him out of the house. When he returned he found her, and the money, gone. Pride was pride, but 40,000 livres was a lot of money, after all.

In 1703 Julie fell in love with Marie-Therese-Louise de Senneterre de Lestrange, the Marquise de Florensac and reportedly the most beautiful woman in France. Marie had also had to flee to Brussels several years before, in her case to escape the attentions of the Dauphin, and the shared experience may have brought the two together. They lived together for two years until Marie died of a fever in 1705. Julie never really recovered from this, and retired from the stage. She spent the next few years putting her affairs in order, reconciling with her husband among other things, before retiring to a nunnery. She died in 1707.

The amazing nature (and quintessential Frenchness) of Julie’s life made her an icon, though her open bisexuality led to her being pushed into undeserved obscurity for many years. The first book about her, Mademoiselle la Maupin by Théophile Gautier, was not published until 1835 and simply uses Julie’s life as a framing device for a somewhat pedestrian romantic triangle (though the book’s celebration of sensuality above traditional gender roles still led to it being banned in several more uptight countries such as the USA). A film of the book in 1966 brought her into the 20th century, and in 2004 a French television series based (very loosely) on Julie’s life once again brought her to the fore. It’s only in recent years, through the efforts of biographers such as Jim Burrows and Kelly Gardiner that Julie d’Aubigny has begun to get the respect she deserves, with a rash of fan drawings appearing on Tumblr throughout 2013. Perhaps only in modern times can we begin to accept that someone like Julie d’Aubigny could, in fact, be real.

Banner image from Julie, chevalier de Maupin. Other images from wikimedia except where noted.

[1] Some sources say 1670, but we’re assured by Kelly Gardiner that the later date is correct.