Jonathan Wild, the Thief Taker General

There’s a story in The Newgate Calendar about Jonathan Wild. A merchant came to him with one of his porters and told him of how the man had been set upon by a gang of thieves. At the time, London had no professional police force but instead relied on private individuals who captured criminals for a reward from the crown, and recovered goods for a commission from the owner. Wild was one of the most famous of these, calling himself the Thief Taker General and even being consulted by the Privy Council on methods of controlling crime. [1] He listened to the porter’s story of being jumped by two or three men and beaten, and then took the merchant aside. Wild explained that his keen sense of deduction told him that the porter was lying, and that he would send for his faithful lieutenant Abraham and together they would figure out the truth. Abraham arrived and the two consulted before Abraham confronted the porter. He first enjoined the man to speak the truth “for, if you persist in a refusal, be assured we shall discover it by some other means”. He then laid out the truth – that a nobleman had asked the porter to fetch his cloak from a tavern and given him his watch as assurance, but it had been a trick and the watch a cheap fake, and while he was gone his cart had been looted. The astonished porter admitted that he had been ashamed to admit that he had been conned. The merchant was amazed, and was even more amazed when Wild retrieved his stolen goods within a few days. Wild accepted the reward but refused to divulge the details of his deductions – unsurprising, really. After all, the reason he knew how the porter was robbed was that it was his men who had robbed him. The Thief Taker General, despite his public face, was in truth the ruler of London’s underworld, sending those who defied him to the gallows or the colonies, and providing the only safe way for thieves to dispose of stolen goods. Far from being the original Sherlock Holmes, Jonathan Wild was instead the original Moriarty.

Wild was born in Wolverhampton around 1683. He was apprenticed as a bucklemaker at the age of fifteen and spent seven years learning the trade before setting up himself in business. He married and had a child, but around the age of 24 he grew restless, and deserted his family to head to London. He supported himself for the first two years either by working at his trade, or by becoming a servant, the accounts are in conflict. What is not disputed is that after two years he had gotten himself into debt, and was sent to Wood Street Compter, a debtor’s prison. There he became a trustee, running errands for the guards. He became so trusted that the guards allowed him to accompany them out to capture criminals, his first introduction to the benefits of being on the top side of the law. He also learned the criminal trade; like Vidocq and Lacenaire he found the prison a “university of crime”. He also met a prostitute named Molly Milliner, and the two formed a partnership that continued after their release.

Wild and Molly were both released in 1712, and began to love together as husband and wife. At first, the two ran a scheme where Molly would draw a likely mark to a secluded area in the course of her business, and Wild would then set on the man and rob him. This proved to be profitable enough that Wild was able to buy an inn (named the King’s Head), with Molly managing a stable of prostitutes from the upper floors. In the end, they parted on less than amicable terms – Wild cut off Molly’s ear with a sword in an argument. [2]

Like a lot of innkeepers at the time, Wild moonlighted as a fence, buying and disposing of stolen goods. The law had begun to crack down on this trade though, with increasingly strong sentences being passed on those caught selling or buying stolen property. It was then that Wild had an idea. He called a meeting of all the thieves that he knew, and made them an offer. Rather than take their goods to fences or pawnbrokers, he said, why not take them back to the owners? Wild approached them, saying that he was acting on behalf of someone who had inadvertently bought the stolen goods, and who sought to restore them anonymously for fear of the new laws. He implied that he felt that this anonymous benefactor deserved some reward, and the victims of the theft were only too happy to oblige. They got their goods, the “benefactor” (which is to say, the thief) got the reward, and Wild got his cut. Soon, he began to get a reputation as a man who could get things done, and it was this that drew Charles Hitchen to him.

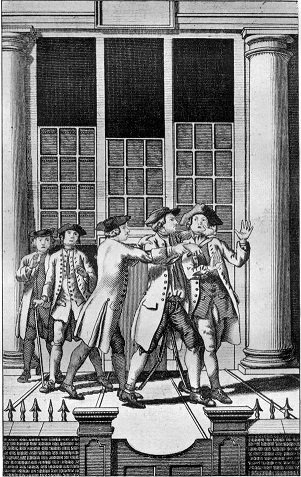

Charles Hitchen was, at the time, the Under City Marshall of London – effectively the public official charged with maintaining order in the city. He had purchased this office for £700 in 1711, and used it to force both criminals to pay him a fee for protection, and businesses to bribe him to steer the thieves away from their businesses. Like Wild, he had hit on the scheme of acting as a “finder” of stolen goods. However, he had been less than discreet in this and was about to be suspended from his office. He needed someone to help him keep his thieves in line, and he recruited Wild to do so. The two became partners for a while, but when Hitchen was reinstated in 1714 he felt he no longer needed Wild. By this time the younger man was firmly entrenched however, and the two battled for control of the London underworld. Wild had the major advantage of knowing who all of Hitchen’s thieves were, and those who would not switch their allegiance to him were turned in for the reward. In desperation, Hitchen attempted to expose Wild as a fraud, but Wild had a trump card – he knew that Hitchen was a homosexual. Exposing this fact (along with Hitchen’s visits to “molly houses”, the gay brothels of the time) was enough to demolish Hitchen’s credibility. Though he kept his office, he was essentially powerless. [3]

Wild’s criminal empire was not confined to mere burglary and fencing. On one occasion his men distracted a noble lady and her attendants and made off with a sedan chair, which Wild was able to recover for her (in return for a suitable fee, of course). Blackmail, too, was a speciality. On one occasion a clergyman made the mistake of relieving himself in a back alley in a less than salubrious area. Immediately a prostitute “brushed against him”, and when he cried out one of Wild’s men grabbed him. Wild threatened to publicise the fact that the priest had been cavorting with the prostitute, despite the naive man’s protestations of innocence. Only a bribe from a more streetwise friend saved him. In another famous example (quoted in Sommerville’s “The News Revolution in England”) he placed an advert with the following text:

“Lost, the 1st of October, a black shagreen Pocket-Book, edged with Silver, with some Notes of Hand. The said Book was lost in the Strand, near Fountain Tavern, about 7 or 8 o’clock at Night. If any Person will bring aforementioned Book to Mr Jonathan Wild, in the Old Bailey, he shall have a Guinea reward.”

The Fountain Tavern was a brothel, and Wild is advertising that he has the book, and that it contains proof of the owner’s identity (the “notes of hand”). The “Guinea reward” is actually the price for the book’s return, with the alternative being that Wild will make sure everyone knows where the owner has been.

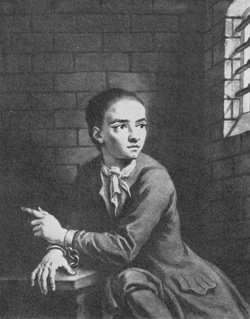

Of course, the good times had to come to an end. After ten years at the top, the cracks began to show in Wild’s empire in 1724. Two years before, he had sent a highwayman named Joseph Blake, nicknamed Blueskin, to jail. Blueskin had informed on his colleagues and doubtless expected rewards, but Wild had found it cheaper to imprison him instead. It’s hard to know whether the betrayal stung more than the sabre cut to the head he got when he was arrested, but when he was released he held a severe grudge against the Thief Taker General. He teamed up with Jack Sheppard, a notorious house burglar who had become emblematic of people’s disaffection with Wild’s shadow regime. Sheppard had been arrested for burglary in April, but had escaped from prison on a rope made from bedclothes. He had been recaptured in May, but had escaped again, this time bringing with him his wife who had also been arrested. In the post-South Sea Bubble [4] era of hatred of the establishment, Sheppard’s exploits made him a hero. At first Wild tried to recruit him, but Sheppard instead teamed up with Blueskin. Wild couldn’t let this stand, so he managed to arrest Sheppard (by getting his wife drunk and finding out where he was hiding). Sheppard was sentenced to death, but managed to escape a third time. By this time Wild was on the warpath, and a posse cornered Sheppard on Finchley Common and arrested him. He was held securely in Newgate, with his feet in irons and the irons secured to the floor. The following month, in October, Blueskin Blake was also arrested. At his trial, Wild gave the damning evidence – evidence Blueskin knew to be false. Enraged, he attacked Wild with a knife (one he had probably kept in the hope of fighting his way free with it). Wild’s throat was slashed, though he survived. The scuffle set off a riot that spread to Newgate, and in the confusion Sheppard escaped from prison for the fourth time. Between that and the attack on him, Wild’s grip on the criminal population was shattered. [5]

Wild had bought a boat to transport any goods he could not “return” to Holland to be sold, with goods being smuggled into the country on the return trip. He made one mistake, however, in crewing the ship with thieves. When five pieces of lace that were being smuggled in went missing, the captain (Roger Johnson) deducted the cost from the first mate’s pay. The mate, enraged, informed on the smuggling to the revenue authorities and the whole thing was ruined. Johnson wound up in a feud with his landlord, Thomas Edwards, as a result of which he was arrested. Fearing he would turn Crown’s evidence, Wild caused a riot to allow him to escape. This was a fatal over-reaching. Witnesses came forward that he had started the riot and he was arrested and charged with helping Johnson escape. Wild was put on trial, charged with a vast array of offences such as receiving stolen goods, having men arrested on false evidence, and an array of other crimes. The most infamous of these was the violent theft the year before of the regalia of the Knights of the Garter. Naturally, he was found guilty.

Wild attempted suicide the night before his hanging by overdosing on laudanum, but succeeded in only making himself sick. The next morning, the 24th May 1725, he was in a stupor, which was not aided by the traditional stops on the way to the gallows for the condemned man to drink in public houses. Daniel Defoe wrote that the crowd was the largest ever assembled for a hanging in the city of London, but if they were hoping for a show they were disappointed. The hangman, who had been a guest at one of Wild’s several (bigamous) weddings, gave him as long as he dared to compose himself. When the mood of the crowd began to turn to riot the hangman’s hand was forced, and Jonathan Wild was hanged.

After his death, Wild became a popular vehicle for satirists to use to attack the unpopular Whig politician Robert Walpole, with accounts of the former usually thinly disguised indictments of the latter. The most famous of these is “The Beggar’s Opera”, one of the greatest pieces of English 18th century theatre. It used the form of Italian opera (popular among the aristocracy at the time) to tell the tale of Peachum and Macheath, two street criminals ostensibly based on Wild and Sheppard, but in reality lampooning the political policies of the day by showing them to be as self-serving as the justifications of criminals. It was wildly popular, though Walpole used his influence to prevent a sequel being produced. This fictional depiction eclipsed the reality, and though Wild has popped up in references since then (most notably, Holmes referred to Moriarty as a successor to Wild), the Thief Taker General, at one point London’s most celebrated detective, and then its most reviled criminal, has largely been forgotten. However, if you wish to see Jonathan Wild for yourself, you can go to Lincoln’s Inn Fields in London. There you will find the Hunterian Museum. Though Wild was buried in St Pancras Old Church next to one of his wives who had predeceased him, he was dug up three days later by anatomists. As a condemned criminal, his body was theirs to dissect, and they did. When they were done, they wired up his skeleton for display, and on display it still is. So if you’re ever in the area, pop in and see the man who once ruled the city of thieves with an iron grip, now forever left grinning at the world.

Images via wikimedia, except where stated.

[1] He recommended they increase the reward for criminals, unsurprisingly. It went from £40 to £140 in a year.

[2] Reportedly he continued to pay her a stipend after they split, though whether this was out of sentiment or to ensure her silence is unclear.

[3] In 1727 Hitchen was entrapped by the “Society for the Reformation of Manners”, a public morality group, and convicted of sodomy. He was sentenced to stand in the stocks, a vitual death sentence as crowds at the time would stone homosexuals undergoing this punishment. Though he was taken down from them early in order to save his life, he died six months later from complications due to those injuries.

[4] If you’ve never heard of the South Sea Bubble, I highly recommend reading “Extraordinary Popular Delusions and the Madness of Crowds”. Short version: Financial crises caused by human idiocy have a very long pedigree.

[5] Sheppard was recaptured less than a month later. Taking no chances, this time he was kept in “the pressing room”, with three hundred pounds of weight on his chest. A petition for a royal pardon for the people’s hero was unsuccessful, and an offer of clemency if he would turn informant was rejected by Sheppard. One last escape attempt with a concealed penknife was foiled when a guard discovered it, and he was hanged on 16th November 1724.