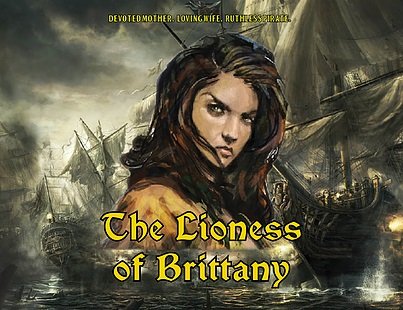

Jeanne de Clisson, the Bloody Lioness of Brittany

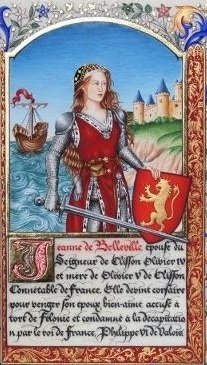

Jeanne de Clisson was born in the French town of Belleville-sur-Vie in 1300. She was the one of the de Belleville family, who had ruled in the area for hundreds of years. In fact, she wound up being the last of the de Belleville family, as her father, the last male heir, died when she was three years old. At the age of twelve, Jeanne was married to Geoffrey de Chateaubriant, the nineteen-year-old heir to one of the key defensive estates in the region. She bore Geoffrey two surviving children, a son who inherited the de Chateaubriant estate and a daughter who inherited the de Belleville estate. Such was the normal procedure, as the law was designed to prevent nobles merging estates and becoming too powerful. In fact, Jeanne’s marriage to Geoffrey was entirely normal, until he died in 1326. In 1330 Jeanne remarried to Oliver de Clisson, and their marriage was far from normal.

Oliver was a widower, who seems to have been almost exactly the same age as Jeanne. Their marriage does not seem to have been one of convenience or alliance, but rather a genuine love-match. It was unfortunate for them both, then, that Oliver could not avoid being drawn into the emerging proxy war between the English and the French in Brittany. The two countries had fought in 1337 over Edward III of England’s claim to the French throne through his mother, Isabella of France. The French claimed that laws passed relatively recently (and directly in response to Isabella’s claim) forbade succession in the female line. It was ironic that the two would wind up taking opposite sides on the issue in Brittany.

The outright war between England and France had ended in 1340 not due to reconciliation, but due to logistics. Parliament had refused to vote Edward the funds to pursue his war, while severed supply lines meant that Philip of France was unable to supply his army. The Pope negotiated a truce between the two men, as was one of his roles in the ancient world, and they agreed to cease all hostilities for two years. It was a stalling tactic, no more, but it did allow them a chance to catch their breath. Almost immediately both sides were looking to gain any advantage they could over each other. In 1341, when Duke John of Britanny died with no direct heir, they had their chance.

There were two potential heirs to John’s dukedom. They were John de Montfort, his younger half-brother, and Jeanne, the daughter of his brother Guy. Since Guy had been older than John de Montfort, then Jeanne should have inherited his claim and been the heir. This was very much Duke John’s wish, as he hated his namesake half-brother and had in fact tried to have his father’s second marriage annulled to de-legitimise his half-siblings. Since Jeanne was married to the king’s nephew, Charles de Blois, John the younger knew that the crown would support Charles to claim the dukedom on his wife’s behalf. John thus decided to pre-empt any official decision by claiming the dukedom immediately through force. The court in Nantes divided on ethnic grounds, with the Bretons supporting John and the French supporting Charles. England saw a chance to get one over on France and threw their support behind John [1] And so the proxy war was on.

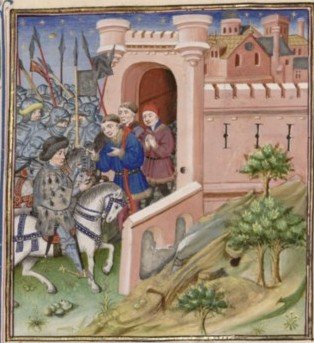

Oliver had fought alongside Charles de Blois in the past, and so he threw in with the French side in what became known as the Breton War of Succession. Most of the nobility made the same choice, and John’s decision to ally with the English only strengthened their resolve. English support also untied the French King’s hands – once news reached him Philip immediately declared Charles the official French candidate, and moved his army to support him. This was a blow to John – the truce still bound Edward from putting English troops on French soil, but not so Philip. The French army managed to reverse most of his conquests. With his battlefield hopes diminished, John went to Paris under a safe conduct to plead his case. Philip broke the conduct, however, and imprisoned him. His wife Joanna then took up his cause and fought valiantly to keep it alive, until June 1342 when the truce finally expired and the English troops finally arrived.

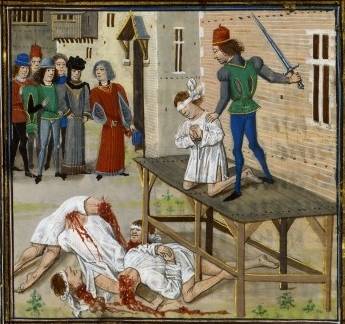

Though it was only Joanna’s martial abilities that had given them a cause to fight, the English imprisoned her to take over for themselves, spreading a story that she had gone mad from stress. The English troops lost no time in advancing, and in November they laid siege to the city of Vannes, which Oliver was defending. After an extended siege the city finally fell, and Oliver was taken prisoner. Two months later, in January, a new truce was agreed. Oliver was ransomed but Charles de Blois was mistrustful of him. He had suspected some treachery in the fall of Vannes, and the low ransom the English asked for Oliver confirmed (in his mind) his suspicions. During the tournament to celebrate the truce, Oliver and fourteen or fifteen other Breton lords, either supporters of John or those considered to have not fought valiantly enough, were taken prisoner. In August 1343, without the public trial his rank should have given him, Oliver was beheaded. His head was sent to Nantes, and his body was put in a gibbet in Paris.

Needless to say, Jeanne didn’t take the news of her beloved husband’s death well. She took her sons to Nantes to show them their father’s head and tell them that Charles de Blois and the King of France had murdered him, and then she returned to her estates. There she immediately sold everything that she could in order to create a war chest. She bolstered her purse by gathering a group of supporters from the followers of Oliver and the other executed nobles, and then payed a visit to the castle of Galois de la Heuse. Galois was a loyal supporter of Charles de Blois, but news had not reached him of Oliver’s execution. He welcomed Jeanne in, and then she and her men turned on him. They slaughtered almost the entire garrison, leaving only a few survivors to pass on the story. By the time Charles and his army arrived, Jeanne’s forces had melted away into the night – along with everything of value from the castle.

Jeanne soon realised that her small force would have little chance of making an impact in the battlefields of Brittany, and so she retreated across the channel with her sons Olivier and Guillaume to seek refuge in England. Sadly Guillaume died on the trip across. She used her fund to buy and outfit three warships. As a clear statement of intent she painted the ships black and dyed their sails red. Then they set off into the English Channel, the 43-year old Jeanne on deck, to play pirate against any merchant vessel they saw flying a French flag. They gained a reputation for savagery, leaving few survivors (though always enough to tell the tale). The nobility who fell into their hands suffered the most, and some stories had it that despite the money to be made ransoming the nobles, Jeanne herself personally beheaded them with an axe before dumping them overboard. It was this reputation that gained her the title of La Lionne Sanglante – “the Bloody Lioness”.

Jeanne’s exploits were not solely limited to piracy – her ships also carried supplies across the channel for the English army, and occasionally raided coastal villages as well. In gratitude for her service, the English granted her lands in the area of Brittany they controlled. Her own lands in French territory had long ago been seized by the French crown, of course. Jeanne’s crusade against the French continued for thirteen years, past the death of the treacherous King Philip in 1350. Eventually in 1356 Jeanne left the pirate life and married an English lord named Sir Walter Bentley. She retired to a castle on the southern coast of Britanny, by the sea, and died peacefully in 1359.

Jeanne may have died, but her family legacy lived on. Her son Olivier, who had been raised in the English court, went to war in Brittany against her old foe Charles de Blois. In the Battle of Auray, where Charles finally met his end, Olivier lost an eye and gained a name – “the Butcher”, for like his mother he took no prisoners. With Charles dead and his blood feud over, Olivier eventually reconciled with France, and in 1380 he became Constable of France, an unassuming title that meant that he was the premier noble in the kingdom, second only to the King in authority and power. Olivier was reputedly the richest man in France when he died, and Francis I (who took the throne in 1515) was a descendant of his. In fact, from then until the 1848 Revolution finally put an end to kings in France, the blood of the Lioness of Brittany and her beloved Oliver de Clisson flowed in the veins of every French king. One suspects she’d have been pleased.

Images via wikimedia except where stated.

[1] Even though, as mentioned, his claim rested on the laws that forbade succession in the female line. In fact those laws explicitly only applied to the French crown and not to noble titles, but that’s why John had to rely on force to push his claim.

[2] Though some historians claim that her privateering had ended over ten years earlier, and that she had married Sir Walter in the late 1340s. Those same historians would point to the 19th century historical romances of Émile Péhant as the primary source for most of the legends about Jeanne. There is definite documented proof of her banditry, though not quite to the extent of legend, and the stories definitely precede Péhant. As with all history, the truth is lost somewhere under the good story.