Germaine de Stael, Romantic Intellectual

Germaine de Stael, one of the most extraordinary figures in an extraordinary period of European history, was born as Anne Louise Germaine Necker in Paris in 1766. Her parents were Swiss, and though not noble were of high station. Her mother was named Suzanne, and was a Protestant pastor’s daughter. She had been in Paris as the travelling companion of a wealthy widow when she met and married Jacques Necker. Jacques had been born the son of a professor of law in Geneva, but had gone into banking and been both lucky and intelligent enough to be successful. His wealth allowed Suzanne to host a highly successful salon. She was possibly even more intelligent than her husband, and her wit and good taste made her salon a gathering place for many influential men.

Jacques chose to complement his wife’s influence by seeking public office, and became a director of the French East India corporation. His success in this role led to him being made the director general of French finances in 1777, effectively putting him in charge of the entire economy. He was sorely needed as France’s support for America in the US War of Independence had left the country severely in debt, and the only way to keep its economy running was to borrow even more. Jacques managed to massage the books and make the country seem more prosperous than it was in order to gain the loans they needed. Some have blamed him for laying the grounds for the French Revolution with this, as his deft presentation contrasted so sharply with the reality his successors found that they decided the Royal family must have been embezzling state funds. Ironically it was the spendthrift habits of the royal family that led to his dismissal in 1781 – he had restricted the amount of funds available to them as part of his attempt to improve the actual state of the finances, and Marie Antoinette held a grudge against him. When she persuaded Louis to block Jacques’ attempt to raise taxes, he walked.

While her father was running the French economy, Germaine was receiving one of the most comprehensive educations imaginable. Her mother Suzanne had wanted to be a writer, but Jacques had discouraged her. So instead she poured her literary ambitions into her daughter, making her a centrepiece of her salon and challenging her visitors to explain their works and theories to the child. The hothouse-style forced intellectual growth was certainly stressful – the young girl had a breakdown at one point, and her relationship with her mother was always strained. But it definitely had its intended effect, and young Germaine had her first book published when she was only 20 years old. It was a romantic drama named Sophie, or the Secret Sentiments. Romance may have been on her mind, as the same year she was married.

We cease loving ourselves if no one loves us.

– Sophie

Germaine’s marriage had been mooted by her parents for several years at that point, but she had no desire to marry any of the suitors they proposed. (Though one of them, the Comte de Narbonne, [1] would actually become her lover later.) The most famous of her potential husbands was William Pitt the Younger, future Prime Minister of Great Britain. [2] In the end she chose to marry Baron Erik Magnus Staël von Holstein, the Swedish ambassador. This was no love match – this was a business arrangement. Germaine was an only child and her father was very wealthy, which the Baron was not. He gave Germaine a title and more importantly official standing as co-Ambassador. This made her an official equal of many of the highest at court, protected her from the very real potential consequences of speaking her mind openly in such dangerous times, and came without the stigma of being a common-born wife – since who expected foreigners to abide by such things? In fact, it’s said that the marriage contract included a guarantee that she would hold this position for at least twelve years.

As the winds of revolution began to pick up, Germaine was initially a supporter of it. Her father’s influence led her to regard the British system of parliamentary monarchy as the best possible, and so she became a member of the Jacobin faction who sought to reform the country and restrict the King’s role within it. It was during this period that she published her second book, a collection of critical essays about the great French philosopher Rousseau (regarded as a patron saint of the Jacobins). This was very well received and helped to make her name as an influential thinker and writer.

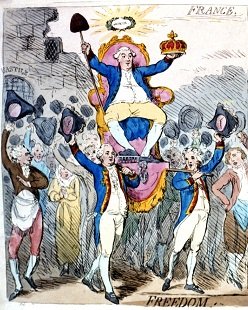

The growing turmoil of the Jacobin reforms and the revelation of the parlous state of the French national finances led to Jacques Necker being reappointed as Finance Minister in 1788. Jacques had an almost mythic reputation among the population, but he could do little to repair the mess that had been made of France’s finances. Worse, he was sorely lacking in political skill and his inept handling of the Estates-General (the elected body in France) and snubbing of the King’s speeches made him an enemy of both. On the 11th of July 1789 he was dismissed by Louis XVI. The public, who still loved him, thought that this was a prelude to Louis seizing back full control of the country. Unrest rose, and culminated in the famous “Storming of the Bastille” on the 14th July. Jacques was returned to office on the 19th July, but he proved to still be incapable of solving France’s problems either financially and politically. He fell from fabour in the public’s eyes, and resigned in disgrace in 1790. So low had he fallen that he was forced to flee France to a castle and estate he had bought in his native Switzerland, in the small town of Coppet.

A week before her father was forced from the city, Germaine gave birth to her third child, a son. Her first two children had been girls named Gustava, after Germaine’s patron and official sponsor Gustav III of Sweden. Neither had survived infancy. While the Gustavas may have been her husband’s children, it’s generally believed that the son born in 1790, named Auguste Louis, was actually the child of Louis Amalric, the comte de Narbonne. He was a regular at Germaine’s salon, and like her was a strong believer in constitutional monarchy. Her influence led to him being appointed as Louis XVI’s Minister of War in 1791. Louis was a hawkish minister, who sought to draw the country into war with Austria as a means of promoting national unity. This put him at odds with the moderate Jacobins, who had no desire for war, and led to his resignation in 1792. The same year Germaine had another son, named Albert, and again it is generally agreed that Louis was probably his father.

Germaine continued to intrigue and became friends (and possibly more) with that most notable of French political rogues, Talleyrand. She attended the National Assembly, and her salon became one of the popular venues for backroom deals among the politicians. As the Jacobins began to turn against the King she also became friends with members of the Royalist faction, including one of their leaders the comte de Clermont-Tonnerre. He was one of those arrested in June 1791 when the royal family, fearful due to the increasing restrictions placed on them, tried to flee the country. He was held in prison for over a year, and when he was released in August 1792 he was murdered by an enraged mob. Mob violence in general was beginning to take hold in Paris, and Germaine must have been conscious that her diplomatic protection only went so far. In truth she had already stretched it in order to protect friends that the increasingly radical authorities had turned their attention on. This included Louis, who she helped escape the country one step ahead of an arrest warrant that would have certainly meant his death. In September 1792, shortly before the “September massacres” swept the city, she followed her father’s lead and fled to Coppet.

In Coppet Castle Germaine reestablished her salon, which became a point of royalist opposition in exile. The main centre for her old comrades was in England though, and she made a visit there in 1793. On the trip she was reunited with Louis as well as meeting up with Talleyrand and other leaders in exile. Her outspoken nature, and the scandal of her relationship with Louis, made her unwelcome in English polite society and so she soon returned to Coppet. There she wrote about the Queen’s execution. In 1794 her mother died. The same year the Thermidorian Reaction (a centrist coup against Napoleon) ended Robespierre’s reign and put an end to the Terror that had seen the streets of Paris and the hills of the Vendée run red with blood. As a result Madame de Staël was able to return to her diplomatic post in Paris.

Germaine’s status as a foreign official helped her avoid the stigma of “émigré”, one who had abandoned France for political reasons. Her husband Erik (who had spent his exile in Holland) also returned to Paris, though Germaine continued to have little to do with him. The new love of her life was Benjamin Constant, a Swiss divorcee and novelist who became her partner in both the physical and mental sense. In Paris Germaine had a front row seat to the rule of the Directory, the ruthlessly centrist group that controlled France during the final years of the 18th century. In 1796 she published De l’influence des passions sur le bonheur des individus et des nations, a series of essays on how emotion rather than judgement was often the decider of destiny. She retained influence at court, and her most far-reaching action was in 1797 when she persuaded the government to allow the return of Talleyrand to Paris. The same year she had her fourth child, a daughter named Hedvig Gustava Albertina. Benjamin was almost certainly the father. In what may have been a related development, she and Erik were separated in 1797. In 1798 the Directory brought Coppet within the borders of French control, when they conquered Switzerland. In 1799 Erik was recalled (the promised twelve years having expired) and three years later he died. Germaine, still legally his wife, came to stay by his side as he died.

1799 also saw the fruition of a plot hatched in part by her old friend Talleyrand to topple the Directory. In their place rose a man that at first Germaine had admired, Napoleon Bonaparte. When she actually saw him as a ruler, however, she found him less than she had hoped.

I had a confused feeling that no emotion of the heart could act upon him. He regards a human being as an action or a thing, not as a fellow-creature. He does not hate more than he loves; for him nothing exists but himself; all other creatures are ciphers.

The distaste was mutual, as Napoleon (rightly) saw her salon as a centre for dissent against his rule. In 1803 he exiled her from the city, forbidding her to travel within forty leagues of it. Many regarded this as unfair persecution and it actually heightened her popularity and influence. Germaine moved her salon to Coppet where it became a European centre for enlightenment thinking – and for conspiracy against Napoleon. This no doubt vindicates his condemnation of Germaine via back-handed compliment, as recorded by his wife Josephine:

This woman teaches people to think who never thought before, or who had forgotten how to think.

As an immediate response to her exile Germaine and Benjamin went on an extended tour of the Germanic states, from Weimar to Berlin and on to Vienna. It was there that news reached her of her father’s illness, swiftly followed by news of his death. She returned to Coppet, though she also travelled to Italy to research her most famous novel, Corinne. It was about an English peer visiting Italy who met and fell in love with an artist, the eponymous Corinne. As the relationship between the two blossoms, it becomes apparent that they both play far larger roles in the international politics of Europe than would seem at first. The novel was notable for being written in French but in a German style, and for combining politics, gender relations, philosophy and the nature of nationality into its tale. “Ought not every woman, like every man, to follow the bent of her own talents?” appeals the heroine, a sentiment that clearly came straight from Germaine herself.

In 1806 she defied the decree of exile from Napoleon (who had by now declared himself Emperor) and quietly returned to Paris to finish Corrine and arrange for it to be published. Once it was released the authorities lost no time in expelling her once again. As with her previous exile she went travelling in Germany before returning to Coppet to write. This time her subject was Germany itself. At the time the ideal of German unity and identity was beginning to form, though it would take a while to coalesce. De l’Allemagne, a celebration of the German Romantic movement, took her two year of near-seclusion to write. Her isolation may also have been prompted by Benjamin leaving her and marrying another woman. She even considered emigrating to America, but she decided that she wanted the satisfaction of having De l’Allemagne published in Paris. Naturally Napoleon regarded the book as nearly sacrilegious, condemning it as “not French”. He had the entire first run destroyed, and Germaine was forced from Paris yet again.

Germaine remarried in 1811, to a much younger ex-Lieutenant named Albert de Rocca. Around the same time she realised that she needed to get out of Napoleon’s empire. While she herself remained untouched, those who remained her friends were making themselves targets for Napoleon’s increasingly dictatorial rule. In May 1812 she sneaked away from Coppet and made her way through Austria to Russia and freedom. From there she travelled to England where she received a hero’s welcome, and was able to finally publish “De l’Allemagne”. Her time in Engand was not without tragedy, as word reached her that her son Albert (an officer in the Swedish army) had been killed in a duel. The following year, with the fall of Napoleon and the restoration of the Bourbon monarchy, she returned in triumph to Paris.

Germaine de Staël spent her final years in Paris glorying in the reputation he had gained. (She did, of course, prudently flee the city one last time during Napoleon’s last fleeting grasp at glory before his defeat at Waterloo.) Her husband Albert fell ill with tuberculosis shortly thereafter, and they travelled to Italy for his health. Her daughter Albertine travelled with them, and in Pisa in 1816 she was married to Victor de Broglie, a liberal politician (and son of a Duke who had died in the Terror) who would go on to be Prime Minister of France. Germaine returned to Coppet after the wedding, and then returned to France to hold her salon that winter. Among the attendees was the Duke of Wellington, the man who had (at least in the popular imagination) put an end to Napoleon. Germaine’s health was clearly failing at this point though, and on the 14th July 1817, after suffering a stroke, she died.

While history in the English-speaking world mostly remembers Germaine for her opposition to Napoleon (leading to condemnation from Napoleonists, of course) her influence on literature was equally far-reaching. Corrine became a major influence on writers as diverse as Walter Scott and George Elliot. Corrine herself became a role model and inspiration for female writers of the 19th century. The poet Felicia Hemans [3] wrote in her copy next to the depiction of Corrine’s ultimate fate: “C’est moi”. Letitia Elizabeth Landon and Elizabeth Barret Browning both modelled their lives on Corrine, and the interpretation of her position in the novel (as hero or as tragic protagonist) became a proxy battle for the right of women to become independent creators. Nowadays, with that battle won in the minds of all right thinking people, Germaine has become better known for a different quote, which she wrote in a letter in 1800:

One must, in one’s life, make a choice between boredom and suffering.

Madame Germaine de Staël, of course, made her choice wholeheartedly for suffering and never seems to have regretted it. May we all be able to say the same.

Images via wikimedia.

[1] Illegitimate son of King Louis XV.

[2] A marriage that would almost certainly have altered the course of history to some extent.

[3] English born of Irish extraction, lived and died in Dublin. Shamefully obscure nowadays – everyone recognises the opening verse of her poem Casabianca, but very few know that she wrote it.