Exploring a Wartime Diarist: Vere Hodgson

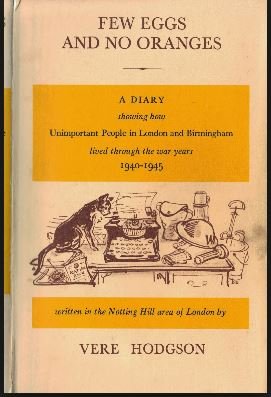

I have long had a fondness for reading other peoples’ letters and diaries (published ones, I hasten to add), and recently I discovered a new diary for my collection. Thanks to the Hodges Figgis bargain section (which sadly is not as large as formerly), I bought a Persephone reprint of Few Eggs and No Oranges: the Diaries of Vere Hodgson 1940-45 for the bargain price of €5. Not bad for 590 fascinating pages of social history from the dark days of World War II. Apart from the splendid title, what really sold me the book was that Vere Hodgson was born and educated in my home city of Birmingham. As this May sees the 70th anniversary of the end of the war in Europe, I would like to give you a flavour of the diary by looking at Hodgson’s account of the last few months of her war experience. I am going to pick out a couple of themes to give a sense of her wartime life. The first will be food (a focus of the book, as you can tell from the title), and I will follow that with some of Vere’s experiences during the latter days of the bombing.

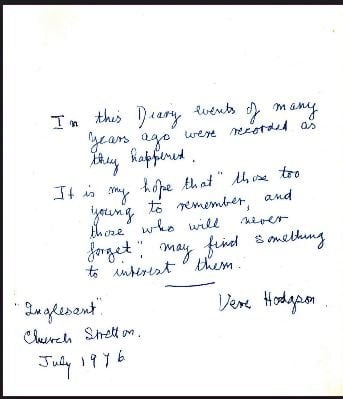

For those who have never heard of Vere Hodgson or her diary (as I hadn’t until recently) I will briefly fill in some background details. As I said above, Hodgson was a Brummie born and bred but by 1935, she was working for a charitable organisation in London, which helped homeless women. The organisation was the Greater World Christian Spiritualist Association, founded by Winifred Moyes. Its headquarters was The Sanctuary, Lansdowne Road, Holland Park. Vere Hodgson formed close bonds with the staff and volunteers who worked there, some mentioned in the extracts below. The diary entries do not mention much of the spiritual aspect of the organisation, though Hodgson talks about astrology and prophecy, interests that apparently many people at that period shared. The diary originated as a way of keeping in touch with scattered family members. Vere wrote the diary on loose sheets and circulated it at home; she then posted it out to her cousin Lucy Hodgson in Rhodesia (modern Zimbabwe). I am amazed that it survived all of that wartime travelling. Vere Hodgson prepared the diary for publication in the 1970s as a direct result of the writer Leonard Mosley advertising for wartime diaries for research into his book Backs to the Wall (1971). Historians Philip Ziegler (London at War 1939-1945, 1995) and Angus Calder (The Myth of the Blitz, 1991) later used quotes from her edited and published diary. The original document is now in Kensington Public Library.

Oranges are the only fruit…

As the title suggests, food in a time of strict rationing was a major preoccupation. Rationing began in January 1940, initially with butter, bacon and sugar. Things do not seem to have been so bad in the countryside where it was easier to grow a range of fruit and vegetables. However, even there, oranges would have been a rarity; in London, it was almost cause for celebration when the greengrocer had stock. On Weds 17th January 1945 Vere writes, “Oranges in Notting Hill today. Not unpacked, but I could return. I spread the good news.” She talks about a local “Disagreeable Greengrocer” who seemed unwilling to part with his fruit, which made me think of grumpy Mr Hodges (AKA the Warden) in Dads’ Army. Her own greengrocer is much more amenable:

But at my shop I was served for three ration books…with five oranges. I looked doubtfully at these lovely Jaffas – but how to divide five oranges among three people! I begged humbly for one more…he considered and caved in. I departed much elated.

On 9th April, Vere records that she had her first ice cream in years, thanks to a friendly farmer’s wife near Birmingham who let her family have some cream to make some. A friend produced a hoarded tin of pears to complete the treat for an Easter lunch. But later in the month, back in London, the diary records:

No Bombs! No spuds either! Went up to my precious Fish and Chip shop – plenty of fish, and he would fry your potatoes if you brought them! We shall have to go on rice –and this is getting scarce.

However, by the end of April, Vere Hodgson was reporting that they were getting more milk and some eggs, the latter having being often hard to obtain over the last few years. Yet this did not mean that rationing was nearly ending; the scheme continued until 1954, with even sweets remaining rationed until 1953.

Vere Hodgson and her Sanctuary colleagues marked the official end of the war with a party after the thanksgiving service at St Paul’s Cathedral. She refers to the gathering as “quite a United Nations”, with the company comprising “A Russian, a Swiss, a Channel Islander, a Scot-cum-Welsh and me, a true-blue English Midlander”. Everybody contributed a tinned something saved for just such an occasion:

We had ersatz champagne. Tinned grapefruit. Salad. Tongue. Tin of crayfish – and a Plum Pudding. All of us had been saving these viands up for a long time. All beautifully prepared by Miss Cameron. It was in Barishnikov’s garden flat, which is bigger than mine. We had lovely coffee, and then he produced his pièce de resistance, some 1898 port …or some such date.

I could not help wondering where Barishnikov had hidden the port during the Blitz. Safely underground probably. Vere was lucky in that she was never bombed out, unlike some of her friends and the many desperate people who came to The Sanctuary (which also survived unscathed) for help. She certainly had some close shaves, but she was able to keep a home together, to offer hospitality, and to share her rations with those less fortunate when required. At one point, she resolved to share her butter ration with Barishnikov to cheer him up when he was “under the weather”, remarking drolly that this was “the height of virtue”.

Bomb Weariness

In the same January 2nd entry in which Vere notes that she invited in “a few Old Dears” to toast the New Year with Ginger Wine and Christmas cake sent by Lucy, she records the state of the bombing. As she listens to the Night Watch Service from St Paul’s Cathedral:

Just as all these wonderful sounds were coming over the air, behold, I heard a Rocket drop. Just to remind us that there are unpleasant things still around, and that the war is not over…Was roused this morning at 3.45am with a terrific crash, fairly near. I registered strong disproval, and dozed off again. Hammersmith way they say.

This is very different from the tone of the earlier entries when Vere would have leapt out of bed for the shelter at such a close attack. At this stage of the war, the diaries indicate that “a great weariness of spirit” was the overriding emotion. It seems as though fear had given way to a simple need for it all to end soon. On March 18th, Vere writes that she and some friends “discussed our general fed-upness with bombs” which must have been a huge understatement. The news bulletins indicated that the Allies were making progress, but bombing on the Home Front had still been intense in the early part of the year.

Vere had recorded heavy rocket attacks during the night of January 4th. This resulted in one hundred deaths in Lambeth and the loss of the organisation’s night shelter there. The warden rang The Sanctuary with the news that they “were in the only room in which the ceiling did not come down”. Vere went on to say that,

They have come over here to sleep, and looked like arrivals from a shipwreck. Mrs Johnson [the shelter matron] really ill, and I do not wonder. They have had to leave the place-just packed a few things and came – too worn-out to bother further with anything…Miss M. and Miss Hoare [the office manager], who so seldom go out, were at the cinema to see Henry V. Nice treat for them with Rockets falling, and to return to learn that our own Shelter was wrecked.

It would probably have been difficult to find another suitable and structurally safe building as a replacement, so this must have had an impact on the services the organisation could offer in that district. It is also worth noting that even in wartime, life still went on as normal as far as possible, even to having a trip to the cinema. On 22nd January Mrs Johnson described her experience of that night and Vere noted it in her diary:

They felt the blast wind round the building three times. The first made them unconscious for some seconds, but next they felt the building falling to pieces around them.

Bombing went on during March, Vere continuing to document the incidents as she had done since 1940. Throughout the diary, she documents all the attacks that she witnesses or hears about, bombs, incendiaries, time bombs, fly bombs, doodles and rockets. On March 4th she writes:

Bombing has stepped up this week after a few days lull, when we thought that they could do no more. Rotten.

After noting that the north of England has also been bombed again, she goes on to observe that:

Even at this stage of the war we are having raiding bombs, rockets and fly bombs – all over at once – I jolly well think we have had enough. I am fed up.

As well as weariness, it seems that by this time there was a fatalistic attitude, as well perhaps as a certain indifference to the danger. During a fly bomb raid in March, Vere comments:

Another well-trained Old Dear was knitting in the corridor on her floor – waiting for the All Clear or The End!

The end of the war, when it finally came, meant a removal of the blackout that everyone had lived with for so long. It was only as April drew on that Londoners realised that the bombing was over. The last raid that Vere records in her diary was a direct hit on the Whitefield Tabernacle in Tottenham Court Road at the end of March. You can feel the uncertainly as April days pass without any further explosions. By 9th April, Vere is thinking of being able to unpack her precious Venetian glass goblet. It seems almost a frivolous urge after all that had occurred, but it must have symbolised to her a return to normal life. On Wednesday 25th April, Vere records that despite the war not being over yet; the blackouts can come down.

We are actually allowed to lift the black-out. But it seems to make us all nervous when we see the lights streaming forth from the house! We have been so well trained after all these years that we still have the feel of the chains that have bound us for so long. When I went up the road the one place from which light streamed bravely out was my police station. I should think they had on every one in the building. But in London generally we are not going to be rushed. We still find it hard to believe the need is over.

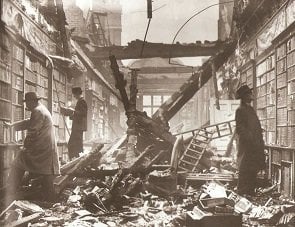

I have only pulled a couple of themes from a small section of Vere Hodgson’s diary, but I hope I have succeeded in giving a taste of the book. What I think is particularly interesting is the entwining of so many strands of news, both domestic and international. Vere Hodgson reports on what she has heard about the progress of the war, bombs falling in her locale and those falling further afield. She also walks the streets of London after a raid to see the damage and records all that she sees. It sounds a touch morbid, but it was a way of bearing witness to all that happened. In the account of her daily life, we meet a large gallery of characters most of whom were volunteers in some form or another. Against a background of war, life went on as usual; cinema, theatre, lunch in the park and dinner out (albeit an austerity one). People still found a way to live in the midst of so much death and destruction. I found the book a truly fascinating read and highly recommend it for its worm’s eye view of war on the Home Front.

Pictures via Persephone Books, Lazlo’s On Lex, Rightmove,and wikimedia.