Ernest Kavanagh | Ireland’s Revolutionary Caricaturist

Ernest Kavanagh was someone who contributed artistically to the era of revolution in Ireland but in our history he has unfortunately been lost among names such as Pearse and Connolly.

Born in Dublin city in 1884, young Ernest received his education from the Christian brothers at Synge Street. He and his sister Maeve drenched themselves in the Irish cultural revival. The Kavanagh siblings had rebel blood flowing through their veins thanks to their Fenian father. Maeve was a gifted writer while Ernest’s talents were poured onto canvas and their artistic givings came from the left side of the republican spectrum.

In the 1901 census, Ernest was listed as an unemployed artist but by the time the next census was taken in 1911, his occupation had changed to insurance clerk. One might think the artist had traded his painting for pen pushing but this occupation as an insurance clerk was one within the belly of the Labour beast: Liberty Hall.

Softly spoken and altogether unassuming, still Ernest managed to strike up a friendship with the fire breathing Big Jim Larkin who secured him a job in Liberty Hall as a clerk in the National Health Insurance section of the Irish Transport and General Workers Union.

Working in Liberty Hall meant that Ernest was in the beating heart of the Irish Labour movement and when he would finish his day job as a clerk in the Hall he would move downstairs to its basement, the epicenter of the union’s propaganda machine, to draw cartoons for the next issue of Larkin’s mouth piece The Irish Worker. He rarely made it home some nights to Oxford Road in Ranelagh, choosing to stay in Liberty Hall to finish his cartoons, tagging them with his trademark ‘E.K’ and helping to assemble the next issue of the left wing newspaper.

Ernest was not alone in his dedication at Liberty Hall, it was a place which buzzed with activity day and night. There formed a strong comradeship between workers and volunteers, one rarely replicated anywhere else. Those who worked and, often lived, in the hall formed a family of union men and women, Socialists and Republicans, but by Easter 1916 their utopia would experience death and destruction.

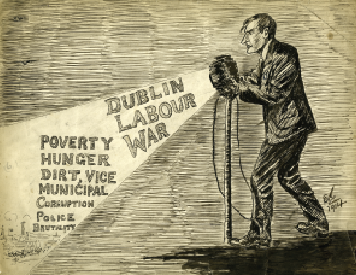

The 1913 Lock-Out would propel Ernest’s cartoons to a new political sphere with his depictions of employer William ‘Murder’ Murphy as a tyrant and the Dublin metropolitan police as nothing more than apes. His stinging sarcasm brought glee to those on strike and revulsion from the bourgeois whom he savaged with his quick wit.

After the Lock-Out, his attention turned to the suffragette movement. Ernest was of the opinion that women were of equal stature to men when it came to work conditions and pay. His cartoons depicting his viewpoint were lauded by the few who agreed with him, such as James Connolly, but many from the conservative side of things in Ireland thought ‘E.K’ was a fantasist for thinking women were equal.

Ernest carried on regardless and when World War One broke out both he and his sister Maeve became media tools for the anti-recruitment movement. The siblings worked closely on a number of anti war pieces for the Irish Worker and other anti-recruitment inclined newspapers. Ernest would produce cartoons to accompany anti-recruitment prose his sister would write and the siblings became a hit within the anti-war movement both in Ireland and further afield when their work ended up in papers in America.

Maeve and Ernest never displayed any sibling rivalry. She would often joke she was her brother’s artistic agent having encouraged and promoted his talent among her literary friends. In the early 1900’s, she even wrote to Arthur Griffith, who was also of the poetic persuasion, to take a look at her brother’s art work for consideration for publication in his weekly newspaper, The United Irishman.

In 1914, Jim Larkin managed to get Ernest a ticket for a major army recruiting rally being held in the Mansion house. His mission was simple, take along his art pad and draw the characters he saw. A week later Ernest’s cartoons hit the pages of The Irish Worker and the images of Redmond among others proved to be extremely popular and the newspaper quickly sold out on the streets of the capital. Larkin sent a copy of the paper to James Connolly who was in Belfast. The Scotsman wrote back to Larkin to thank him and to look after the young cartoonist well because his pictures were ‘dandy’.

Ernest Kavanagh had utter loyalty to the likes of Larkin and Connolly and adhered to the value of their left wing cause, but he never joined its armed struggle. Like the rest of his comrades at Liberty Hall who joined the Irish Citizen Army, Ernest stood out and bucked that trend. This gentle and soft natured man could not bear the military discipline that membership of such a group would cost him. Hence he chose to remain a civilian symapthizer in the fight for a socialist republic. His refusal to don a citizen army uniform, did not cause any friction with his comrades at Liberty Hall, his cartoons proved he was too valuable to make an enemy of and anyway, his good natured manner marked him as a lad you couldn’t dislike.

On Easter weekend 1916, Ernest had an inkling something may kick off, but he wasn’t sure. At the worst , Ernest thought maybe the Citizen Army might raid somewhere for arms, or at the least stage a military parade on the streets. On Good Friday, he had his photograph taken, the only known picture of him, with a relaxed smiling face looking out at us, unaware that his life would be extinguished four days later.

At noon on Easter Monday, Connolly led the Irish Citizen Army along with Pearse’s Irish Volunteers into the GPO. The fight for freedom had begun and Ernest who was enjoying a much sought after rest was startled by the sound of gunfire coming from the city centre. As he was not a member of the Citizen Army or the Irish Volunteers, Ernest found he had no role to play and all day Monday, his thoughts turned to his Liberty Hall comrades as reports steadily streamed in to Ranelagh from eyewitnesses on the front-lines, at the GPO and Dublin Castle. Ernest’s sister Maeve was on dispatch duty down the country and this also played on his mind.

Ernest could not sleep well Monday night and by sunrise on Tuesday morning he decided to head to Liberty Hall and offer his assistance. He would atone for his guilt and take up arms at the barricades and this thought whirled around in his mind as he skipped from Tara Street and crossed over Butt Bridge sometime after 7 o’clock on the morning of April 25th. He reached that bastion of Labour power, Liberty Hall, and as he walked up its steps and knocked on the door a series of bullets struck Ernest. In her military witness statement from the 1950s, Ernest’s sister Maeve stated how her brother was ‘ riddled with bullets fired by soldiers in the Custom House.’

The lifeless body of the 32 year old cartoonist was brought to Jervis Street hospital, before being taken to Glasnevin Cemetery where he was laid to rest in the St Paul’s section of the famous necropolis.

What would have become of the talented artist in the pivotal years after the Easter Rising will never be known. Perhaps he would have carried on the fight of the working class, the suffragettes and anti conscription movement. He would have surely lit up newspapers with his witty and sarcastic political drawings of the day. Ernest Kavanagh may not have been an Irish rebel in the combatant sense but his pen was his sword and his battlefield was on the pages of the Irish Worker newspaper where he weekly struck a blow for a socialist republic.