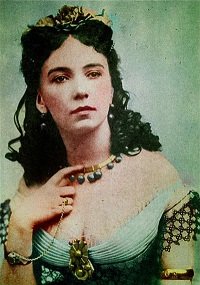

Cora Pearl, Parisian Courtesan

Cora Pearl, one of the most infamous woman in the empire of Napoleon III, was born plain Emma Crouch in Plymouth, England. She was probably born in 1835 though she would claim later to have been born in 1842, shaving seven years off her age. Her father was Frederick Crouch, a cellist who also composed songs. He abandoned the family in 1847 and fled to the United States. The reason for this was to escape his debts, though ironically shortly after he did so a song of his named Kathleen Mavourneen was adopted by the Irish soprano Catherine Hayes and became famous, giving him some reflected glory. In America he fought for the Confederacy, and his ballads were popular among the aristocracy of the south. Frederick remarried (bigamously) and had several more children. His abandoned wife, meanwhile, told her children (including Emma) that their father had died, and promptly replaced him with a rich lover. This was Emma’s introduction to how grown-ups lived their lives.

Cora Pearl, one of the most infamous woman in the empire of Napoleon III, was born plain Emma Crouch in Plymouth, England. She was probably born in 1835 though she would claim later to have been born in 1842, shaving seven years off her age. Her father was Frederick Crouch, a cellist who also composed songs. He abandoned the family in 1847 and fled to the United States. The reason for this was to escape his debts, though ironically shortly after he did so a song of his named Kathleen Mavourneen was adopted by the Irish soprano Catherine Hayes and became famous, giving him some reflected glory. In America he fought for the Confederacy, and his ballads were popular among the aristocracy of the south. Frederick remarried (bigamously) and had several more children. His abandoned wife, meanwhile, told her children (including Emma) that their father had died, and promptly replaced him with a rich lover. This was Emma’s introduction to how grown-ups lived their lives.

Emma was packed off to a convent in Burgundy, where she was taught, among other things, etiquette and French. That may not have been the only education she received, however – there are stories [1] that she had several lesbian affairs while she was a student. When she returned to England, she went to London to live with her grandmother. She got a job as a milliner’s assistant, selling hats. However, like so many young girls who came from the country to London, in 1855 she got drawn into the city’s massive prostitution industry. It’s claimed [2] that this was the result of Cora being talked into visiting a bar with a man, drinking until she passed out, and then waking in a hotel bed with her virginity taken and £5 (around £250 in modern money) sitting on the nightstand. The apocryphal fake memoir of her life from 1983 claims that this left her with “an instinctive horror of men”, and alleges that she therefore forswore the idea of love. If so, she had a strange way of expressing that horror as she soon entered fully into life as a part-time Victorian prostitute. This was far from uncommon – attractive young shopgirls were frequently propositioned by male customers, and most found the opportunity to make easy money difficult to resist. The majority of them never became professional prostitutes, but eventually gave up the trade when they married and left their jobs, as was expected at the time. Some, however, instead left their respectable lives behind and Emma was one such girl. She moved out of her grandmother’s house and rented a room in Covent Garden, where she entertained a series of gentleman callers. And then she met Robert Bignell.

Bignell was an outwardly respectable gentleman (he was a member of the Brentford local council) who gave his profession as a wine merchant. What he is best remembered for, however, is the business he ran out of the building above his winecellar – the Argyll Rooms. This was before nightclubs became a part of culture, but the Argyll Rooms could make a claim to be one of their earliest incarnations (though with gambling rather than music as the main draw). Naturally, the place was a great working ground for the higher class of prostitute, and Bignell was far too canny a man to miss the opportunity to run them himself. Emma was one of those he recruited. She swiftly became his favourite, and effectively his mistress as well as his employee. Working in the Argyll Rooms was an education for Emma in the realities of her trade, as she could see all classes and types of Victorian sex worker. Some, like her, worked the floor with the managements blessing. Some lurked outside, too low class to be permitted to enter but hoping to catch the eye of some gent as he left. And some arrived as guests, dressed in the highest fashion and on the arm of nobleman or captain of industry who paid their bills. The sight of these women (some of them mistresses, pledged to a single lover, and others courtesans, ladies who took multiple lovers) inspired Emma. Clearly this was what she should aim for. Having managed to become Bignell’s mistress so easily, she knew that she could manage it, though she also knew that her history in London would be a liability. It was when Bignell took her on holiday to Paris that the solution occurred to her. She spoke French fluently, and she fell in love with the city. When he returned to England, she stayed behind – but not as plain Emma Crouch. Instead she rechristened herself as Cora Pearl.

Of course, starting over meant once again starting at the bottom, and initially Cora had to resort to working the street. Things improved when she made the acquaintance of Monsieur Roubisse, a high class procurer. He saw her potential, and spent some time grooming her for entry to high society. In 1860 she made her debut, and was an instant success. At the time France was an empire – the Second French Empire, ruled by Napoleon III. He was the nephew of the famous Napoleon Bonaparte, and had been elected as the first President of the French Republic in 1848. When he was blocked from running for a second term, he launched a coup d’etat and seized power, taking on his uncle’s old title of Emperor. In classic Machiavellian style he front-loaded his repression, eliminating opponents and censoring media through the 1850s before beginning to relax his rule around the time Cora appeared on the scene.

Cora’s first major conquest was Francois Victor Massena, Duke of Rivoli, Prince of Essling, and noted ornithology enthusiast. He was enamoured of Cora, showering her with gifts and money, paying for her staff and buying her first horse. Cora took to the saddle “like an Amazon”, as one admirer noted. Her skill at riding helped her to stand out from the crowd, and gave her an avenue to attract a large number of additional lovers including Prince William of Orange, heir to the throne of the Netherlands (known in Paris as “the Lemon Prince” for his voluntary self-exile when his parents would not let him marry the girl he chose). Francois does not seem to have been a jealous lover, and was also willing to bankroll Cora’s visits to the gambling dens of Paris – a habit she had doubtless acquired in the Argyll rooms. By the time he died in 1863 Cora was firmly established as a demimondaine, one of the butterflies who flitted among the bright lights of Parisian society. [3]

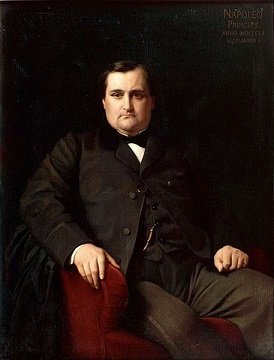

There are many stories of Cora’s exploits in high society during the 1860s (including one notorious tale where she had herself served naked on a silver platter), though it’s hard to separate fact from fiction. It’s well attested that she appeared on stage as Cupid in a production of Orphee aux enfers by Jacques Offenbach (which is best known for Infernal Galop, the music which traditionally accompanies the dancing of the Can-Can). Her performance was damned with faint praise in the papers: “It was a success of a kind…”. In 1868 she snagged her most notable long term lover – Napoléon Joseph Charles Paul Bonaparte, usually known as Prince Jerome Napoleon, cousin and close adviser of the Emperor.

Prince Jerome was a more jealous lover than Francois had been, though all this meant to Cora was that she could use the frisson of imperial displeasure to raise the generosity of her other lovers to even greater heights. An evening in the company of Madame Pearl could cost up to ten thousand francs – about £100,000 in today’s money. (It’s an inexact conversion – by some measures it could be as high as £200,000.) Her jewellery collection was valued at a million francs, not to mention her horses, houses and dresses. (She is reported have once received a lingerie bill for £18,000.) There is evidence that she sent home money to her mother in Plymouth – and that she also sent money to the father who had abandoned her, his career having suffered after the loss of the Confederacy in the American Civil War. The last half of the 1860s were Cora’s golden period, where she became a celebrity known throughout Paris. Alfred Delvau, a journalist and writer who was once prosecuted for writing a dictionary of erotic slang, wrote of Cora in his book Pleasures of Paris:

You are today, Madame, the renown, the preoccupation, the scandal and the toast of Paris. Everywhere they talk only of you…

The first shadow to fall on Cora’s world was that of war. In 1870 Otto von Bismarck, seeking to unify all of Germany under his rule, deliberately provoked a war with France over a diplomatic incident. Though the French had the superior military at the time and were confident they could win, the Germans had known that the war was coming and were far better prepared. The armies of France were defeated at every turn. Cora, like most of the upper class, did her part for the war – her homes became military hospitals, and she donated a large part of her fortune towards medical aid for the soldiers. Napoleon III was captured by the Germans, leading to a republic being re-established in Paris. Then the capital itself was put under siege, and fell in January of 1871. Germany dictated a peace on punitive terms that had the long-term effect of laying the groundwork for World War I, and the short term effect of provoking a short but bloody revolution. The Paris Commune, an early socialist revolt, was swiftly suppressed by the French army in “the Bloody Week”, but the reminder of the Revolution that was less than a century in the past had a salutary effect on the national psyche. The French people had clearly had enough of Emperors, and the Second French Empire was very definitively at an end.

The imperial family had fled to London in advance of the siege, and initially Cora had gone with Prince Jerome. When the family settled in the Grosvenor Hotel however, the management made it clear to Cora that they would not tolerate her presence. [4] She returned to Paris, but found that the new regime had led to a shift in public tastes. Her ostentatious displays of wealth were now considered gauche rather than impressive, and the wealthy lovers who had previously come knocking at her door were now in much shorter supply. In addition she was not getting any younger, and though she claimed to be only thirty the seven years she had shaved off were beginning to show. So it was that she was forced to be less discriminate in her choice of lovers, and so it was that she could not afford to turn away young Alexandre Duval. He became obsessed with her – dangerously so – but his generosity let her maintain her lifestyle. Eventually however, Cora had enough. Whether it was his increasingly aberrant behaviour, or whether she heard rumours that his family were about to cut off his income, she refused to see him any more. If it was the former, it was a wise move, as Alexandre immediately decided that if he could not have Cora, nobody could.

On December 19th 1872 Alexandre turned up at Cora’s house. The servants had been ordered to refuse him entry, but he produced a firearm and tried to force his way in. In the ensuing struggle the gun went off, seriously wounding Alexandre. Though the story told by the gossips was that Cora left him to bleed on the doorstep until the morning, the New York Times reports that she actually brought him in, sent for a doctor, and spent a sleepless night by his bedside. He eventually made a full recovery, but Cora’s reputation did not. Her fortunes went into a decline, and the final straw came in 1874. Prince Jerome, who had continued to maintain her, wrote to tell her that he would no longer be paying any of her bills. As she reached her fortieth birthday Cora was forced to realise that the party was over.

The end was accelerated by Cora’s complete lack of any financial acumen. Had she liquidated her fortune and invested it she might have been somewhat comfortable, but she was unwilling to part with her houses, jewels and horses, and so sold them all piecemeal until she was left with nothing. By 1880 she had just one house remaining, and in 1883 she returned to straight-forward prostitution to maintain herself, renting a flat in Paris where she took middle-class clients, a far remove from her glory days. Her gambling addiction helped to contribute to her downfall. One of her old friends met her in 1885 sitting outside a casino in Monte Carlo, “weeping pitifully, handsome but much bedraggled”. That year she sold her last remaining house, and moved into a boarding house. In an attempt to restore her fortunes she wrote her memoirs, but discretion (or discreet pressure) undercut Cora’s last throw of the dice – names were obscured, and details were absent, dooming the book to poor sales and obscurity.

Unknown to Cora, however, even if her memoirs had been a success they could not have saved her. She was already suffering from intestinal cancer, and on July 8th 1886 the disease claimed her life. Her funeral was sparsely attended, but one of her former lovers anonymously covered the costs to ensure that she would be shown the respect she deserved. She was buried in Batignolles Cemetery in her beloved Paris, under the name she had abandoned, Emma Eliza Crouch. Her death was reported in newspapers around the globe, a last reminder of a more glittering world now gone forever.

Images via wikimedia except where noted.

[1] At this stage I should probably give a disclaimer. While Cora Pearl did publish a set of memoirs during her life, there was also a hoax in the 1980s by historical romance author Derek Parker where he published a set of “newly discovered” editions of the memoirs that turned out to be complete fiction (though based on accounts of Cora’s exploits). The disclaimer is that I don’t have access to either of these books – simply second-hand sources that quote them – and though Parker’s hoax was quickly exposed, the lies he wrote have still managed to get halfway around the word before the truth got its boots on. In fact, his forgery is still being sold as a genuine memoir. As such, while I’ll do my best to avoid perpetuating his fabrications, and call them out where I suspect them, they’ve penetrated the narrative to such an extent that I cannot guarantee I’ll succeed. So add an extra grain of salt to the heaping spoonful you should take all historical writing with.

[2] This may be one of Parker’s inventions, though if so it’s been indiscriminately picked up by a lot of people.

[3] While rich men taking mistresses was not unique to French society, the fact that they were considered almost respectable was.

[4] Astonishingly the Grosvenor Hotel now has a “Courtesan Suite” dedicated to the woman they thought themselves too good to accommodate.