Clotworthy Skeffington, Eccentric Earl

Clotworthy Skeffington the Fifth, heir to the Earldom of Massereene, was born on the 28th January 1742 in County Antrim. His impressive name came from John Clotworthy, a son of the High Sheriff of Antrim who backed the right horse during the English Revolution and was created Viscount Massereene and Baron Loughneagh. He had been succeeded by his son-in-law, John Skeffington, who had given his wife’s maiden name to his son as a forename. Thus the third Viscount was the first Clotworthy Skeffington. The fourth Viscount, named Clotworthy after his father, was most noted in history for being the rejected suitor of Mary Pierrepoint, later Lady Mary Wortley Montagu. The fifth Viscount (father to the Clotworthy we are interested in) was promoted to Earl of Massereene in 1756, when Clotworthy the younger was only fourteen years old. A year later the new Earl died, and young Clotworthy became the second Earl of Massereene.

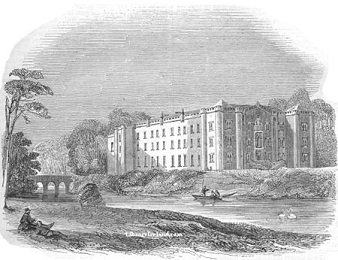

Massereene is (as the secondary title of the first Viscount would suggest) a small townland on the shores of Lough Neagh, just outside Antrim town. Here, in stately Antrim Castle, Clotworthy Skeffington grew up. One story has it that he fell off a horse in his youth and broke his collarbone such that it never properly healed, having a permanent effect on his posture and leaving him with a habit of crossing his arms and grasping his shoulders while at rest. (His later eccentric behaviour was sometimes explained by the assumption that the fall had also injured his brain in some way.) Young Clotworthy left Massereene in 1758 to attend Corpus Christi college in Cambridge, but when he assumed control of his income at age 21 he felt no compulsion to return. He left his mother Anne (who he disliked) to run the family estates, while he lived as an aristocratic dandy among the capitals of Europe. It was a pleasantly unproductive and totally standard lifestyle up until the late 1760s when it all came unstuck in Paris, over a scheme to import salt.

At least, that’s the most interesting version. Some histories claim that Clotworthy’s sudden indebtedness came from a fraudulent game of cards, but the amount he wound up owing (some £30,000 in 18th century money) makes that unlikely. The most common story is that he was persuaded by a man named Vidari to invest in a scheme to import salt from the Barbary Coast (possibly in an attempt to evade the King’s tax on salt produced in France). Vidari was a swindler and soon vanished with the money invested in the salt business, leaving his partner Clotworthy responsible for the money owed. He was imprisoned for debt in 1769, and his long-suffering mother was willing to send the funds to have him released. However there was one issue – in order to pay off the debt, Clotworthy first had to assume responsibility for it. But this he refused to do, claiming that he was a victim of fraud. It was a stand on principle that would see him spend two decades in French prisons.

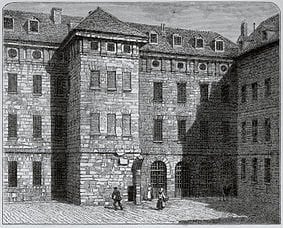

Of course, for those with Clotworthy’s level of income, life in a French prison was not so harsh a trial. After a failed escape attempt in 1770 (where he bribed a guard, who pocketed the money and then refused to help him), Clotworthy decided to simply stay in prison for the next twenty-five years. After that, by French law, his debts would be absolved. He reportedly spent £4000 a year on ensuring he had the best lodging possible, [1] and his Parisian friends (and mistresses) were more than happy to visit the prison and enjoy the cooking of his private chef. At first he was imprisoned in Fort-l’Evêque, a debtor’s prison that centuries earlier had been the seat of the Bishop of Paris and the site where those accused of heresy were tortured into a confession. By the 1770s it had primarily become known as where they held those who were imprisoned without charge by royal decree (enabled by the hated legal system of the “lettre de cachet”). However debtors such as Clotworthy were also imprisoned there. In 1780 Jacques Necker, France’s legendary finance minister of the period, visited Fort-l’Evêque and decided it was no longer up to standard, and so August of that year it was closed. Clotworthy, along with the other residents, was transferred to La Force prison.

La Force seems to have been much less salubrious than Fort-l’Evêque, especially as the encroaching Revolution led to less corruption and hence less comfortable living conditions for Clotworthy. In a letter to Francis Osborne (British Foreign Secretary and Marquess of Carmarthen), he described being imprisoned alone “save for the vermin and a mouse which I taught to come for food”.

La Force did have one silver lining for Clotworthy however – Marie Anne Barcier, daughter of the Governor of the prison and reportedly a great beauty. The two began a relationship, and he may have even secretly married her in a ceremony of dubious legality. She twice attempted to help him escape but failed. Finally on the 13th July 1789, during the riots in Paris that would climax with the storming of the Bastille the next day, a mob broke into La Force and liberated the prisoners. Marie Anne would later claim credit for having inspired them to this. Clotworthy first took refuge at the British Embassy and then fled to Calais. He was almost detained at the border crossing, but he managed to make his way across the Channel to Dover. He was the first passenger to leave the ship when it made landfall, and fell to the ground kissing it and proclaiming

God bless this land of liberty!

On the 19th August he and Marie Anne were married, officially, at the church of St Peter Upon Cornhill in the centre of London. The happy couple visited Antrim briefly, but separation had not lessened Clotworthy’s distaste for his mother’s company and they returned to London fairly quickly. However the honeymoon was soon over – Marie Anne had a taste for extravagance that Clotworthy disapproved of, while he himself may have wound up in debt once again over a failed business proposition. However the true cause of their relationship issues was Clotworthy’s roving eye. He had taken a fancy to a 19-year old servant girl named Elizabeth (her surname was either Lane or Blackburn, sources vary). He abandoned Marie Anne (who was suffering from angina), giving her a pension of £300 a year. She claimed this until she died of a heart attack in 1803, only 38 years old.

Elizabeth did little to settle Clotworthy down. He became involved in more swindles and schemes, and ended up £9000 in debt to a man named Whaley. This landed him back in a debtor’s prison, and it was only through appealing for a loan of £4400 from the Earl of Leitrim, husband of his elder sister Elizabeth, that he was released. In return he gave the Earl a mortgage on his estates in Antrim, though the Earl never executed it. By this time Clotworthy was scandalously living with Elizabeth, on the promise that he would marry her once his wife was dead. It may have been part of the agreement between Clotworthy and his brother in law that led to him leaving London in 1897 and returning to Antrim Castle.

It was in Massereene that Clotworthy’s conduct, always eccentric, became legendarily so. His experiences in France had left him convinced that a revolutionary war in Great Britain was inevitable, and so one of his main pursuits was training a company of men in martial combat to resist this and protect him. However all of this training had to be done without weapons, as he could not secure any. Instead his men would pantomime presenting arms, and simulate firing a rifle by clapping their hands. He had them march in special drills which he formulated himself, and which he gave names like “Serpentine”, and “Eel in the mud”. Unsurprisingly, official permission to incorporate his company as militia never came. This was far from his only eccentricity. He was infamous for having dinners on the roof of his castle, an enterprise which required having the furniture moved up on winches. When Elizabeth’s dog died he had fifty of the local dogs, wearing white scarves, serve as a guard of honour at the funeral. One neighbour is said to have said that:

[She] had previously heard a report that he was a lunatic, but she then thought that if he was a lunatic he was the pleasantest one she had ever met.

Of course, not everyone was so charmed. He seems to have hated his mother, commenting as she lay in her sickbed that “Devils are waiting to take her to hell”. The joke was on him, as she would survive him by three months. Elizabeth encouraged this rift and sought to drive a wedge between Clotworthy and his family, the easier to take over his estates. She was cheating on him with a local man named George Doran, the son of a former Catholic priest who had converted to Anglicanism. Young Doran, along with his parents and sisters, all moved into Antrim Castle. Clotworthy doesn’t seem to have taken this amiss as after Marie Anne’s death 1803 he (faithful to his promise) married Elizabeth.

In February 1805 Clotworthy died aged 63, and his will came as a shock to his family. Though his titles passed to his brother Henry he had left his estates entirely to Elizabeth, giving his brothers and sisters a single guinea apiece. (His mother, who passed away in May, seems to have been neglected entirely.) Naturally his brothers challenged the will in court, on the ground that Clotworthy had not been of sound mind. They had a great deal of evidence to back this up, of course, but they may have decided that they would prefer not to have the stigma hanging over the family. Instead they paid Elizabeth off to the tune of £15,000 and £800 a year for life, and the will was dismissed on the grounds of her “undue influence”. Elizabeth went on to marry George Doran and have a son named Patrick. Henry died childless in 1811 and the title passed to the youngest Skeffington brother, named Chichester. Chichester passed away in 1816. He had no sons, but had a daughter named Harriet. She inherited the estates, and the titles of Viscountess Massereene and Baroness Loughneagh, but as a woman she could not inherit an Earldom. So ended the Earls of Antrim Castle.

Images via wikimedia except where stated. Banner shows an engraving of French aristocrats in prison, via Antique Prints.

[1] Which if kept up for 25 years would amount to over three times the size of his original debt.