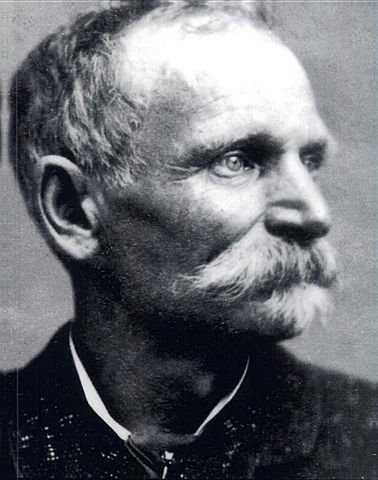

Charles Bowles, AKA “Black Bart”, the Outlaw Poet

The urge to reinvent yourself is often a strong one. The idea of a “mid-life crisis” is more of a cliché than an actuality, but people do often find themselves stopping to take stock and re-assessing themselves. Sometimes we all take a look in the mirror and find that we don’t like what we see. Of course, few of us immediately decide to throw aside a life of quiet respectability and take up one of crime instead, but throughout history more than one person has decided that if life wasn’t going to give them what they wanted, they were going to take it. Charles Bowles was one such man.

The urge to reinvent yourself is often a strong one. The idea of a “mid-life crisis” is more of a cliché than an actuality, but people do often find themselves stopping to take stock and re-assessing themselves. Sometimes we all take a look in the mirror and find that we don’t like what we see. Of course, few of us immediately decide to throw aside a life of quiet respectability and take up one of crime instead, but throughout history more than one person has decided that if life wasn’t going to give them what they wanted, they were going to take it. Charles Bowles was one such man.

Charley (as he was known) was born in 1829 in Norfolk, England. When he was two years old his family emigrated to America, where his father bought a farm in Jefferson County in upstate New York. Charley had a fairly normal country childhood, excelling at wrestling and surviving a brush with smallpox. In 1849, when he was 20 years old, he set out with his cousin David to the gold mines of California. They spent a year there with no success, before returning to Jefferson. Charley had the gold mining bug, however, and he persuaded David to return to California with him and his brother Robert. After two years of mining on this trip, all Charley had to show for it was the graves of his brother and cousin, carried off by the diseases that regularly did the rounds of the mining camps. His dream of striking it big in tatters, he returned home.

In 1854, Charles Bowles moved to Illinois where he married Mary Elizabeth Johnson and lived a life of quiet respectability. The pair had four children, and there Charley might have spent the rest of his days if fate hadn’t intervened. The American Civil War broke out, and Charley volunteered to serve the Union. He joined the 116th Regiment of the Illinois Infantry, and rose through the ranks to First Sergeant. He even had the prospect of a commission to Lieutenant, but in a battle in Georgia he was severely wounded. He recovered in time to rejoin his unit for the battle of Atlanta, but he never got that promotion. He was discharged on June 7, 1865, around a month after the Confederate President officially declared his surrender.

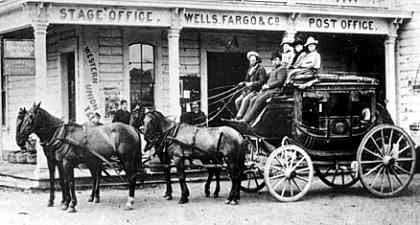

His war service seems to have reawakened Charley’s desire for adventure. His family moved to Iowa and set up on a farmstead there, but Charley couldn’t settle to it. In 1867, with his wife’s backing if not blessing, he set out to the silver mines of Montana. At first, he wrote to her regularly, telling her of the claim he had staked. The last letter she received in 1871, however, had a less cheerful tone. In it, he told her of being visited by a gang of men who claimed to be working for Wells Fargo, one of America’s earliest corporations. They tried to buy his claim, but the price was lower than he would have accepted and he refused. In retaliation, they diverted the stream leading to his claim and cut off his supply of water. Without water, he could not operate his Long Tom, a long sluice used to separate out silver from gravel and clay. He was forced to abandon his claim and head to California, swearing that he would get back what was owed him from Wells Fargo.

That letter was the last that Mary would receive from her husband for over twelve years, and she assumed that he had died while walking to California. (Charley didn’t like riding horses, and walked most places he went.) In a way, she was right. The man who arrived in California called himself Charley Bolton. He dressed well, ate in the best restaurants in San Francisco, and seemed to all who saw him as a respectable old man retired from a successful life. Some stories have it that he taught in a local school for a while, but that wasn’t the primary source of his funds. Instead, Charley Bolton preyed on the men who Charles Bowles blamed for ruining his chance to strike it big. Wells Fargo.

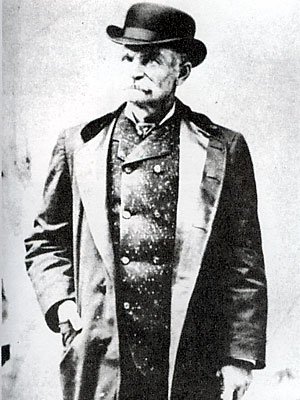

On July 26, 1875, a Wells Fargo stagecoach was stopped by a masked figure, wearing a flour sack with eyes cut out and a long coat to hide his clothing. The driver [1] was at first disposed to cause trouble, but the figure warned him that he was not alone. He gestured towards rifle barrels, poking out from cover. He demanded the Wells Fargo strongbox, and the driver handed it over. As he drove off, he saw the robber attack it with a hatchet, stealing $348 in coin, note and gold. Charley’s first stagecoach robbery had gone off without a hitch.

Over the next eight years Charley robbed twenty eight Wells Fargo coaches, stealing a total of around $48,000 in notes, coin and gold – more than enough to live a life of leisure and luxury. He only ever took the strongbox – on several occasions, scared passengers would try to give him their possessions, but he always refused, insisting that he had no wish to rob them. Although he carried a shotgun, there is no record of him ever firing it, and it may not even have been loaded. The greatest mystery around him came from the poems he left at the fourth and fifth of his robberies. The first was an angry denunciation of those he robbed:

I’ve labored long and hard for bread,

For honor and for riches

But on my corns too long you’ve tread,

You fine-haired sons-of-bitches.Black Bart, the P o 8

It also had a postscript:

Driver, give my respects to our old friend, the other driver.

I really had a notion to hang my old disguise hat on his weather eye.

The second seems more philosophical in tone:

Here I lay me down to sleep

To wait the coming morrow,

Perhaps success, perhaps defeat

And everlasting sorrow.

Yet come what will, I’ll try it once,

My conditions can’t be worse,

And if there’s money in that box,

‘Tis money in my purse.Black Bart, the P o 8″

The signature on these was a source of much debate. As Charley later related, the name “Black Bart” was taken from a dime novel called “The Case of Summerfield”, by Wiliam H Rhodes. [2] The villain of that novel was Captain Bartholomew Graham, a man with a bushy black beard and piercing blue eyes. Charley was blond turned to grey and had a moustache, but with his sack mask all that the drivers could see of him was his blue eyes. He never explained the meaning of the “P o 8″, though it may simply have been a jokey way of writing “poet”.

Charley had one close call in 1882 when a driver named George Hackett decided to open fire on him rather than give up the strong box. He escaped, but a bullet creased his scalp and left a permanent scar. Apart from that, however, most of the drivers did not feel compelled to take up arms in defence of Wells Fargo, even when a reward of $800 was posted for his capture. On November 3, 1883, his luck ran out. Jimmy Rolleri, a friend of the stagecoach driver Reason McConnell, rode along with his friend as Reason had mentioned seeing a lot of deer on his early morning runs and Jimmy fancied doing some hunting. There were no passengers in the coach, but the strongbox contained nearly five thousand dollars worth of gold and had been bolted to the floor for security. Halfway up Funk Hill Jimmy got out and set off into the woods to hunt, while Reason went on with the coach. At the top of the hill Charley stepped out with his shotgun and flagged him down. He demanded to know who the person he had seen getting out of the coach was, and Reason lied and said it was a kid looking for lost cattle. He didn’t want Charley to know that it was a man with a gun. Charley demanded the strongbox, and Reason said that he couldn’t give it to him as it was bolted to the floor. Charley ordered him out of the coach, and sent him off down the road, then began attacking the strongbox with a hatchet. After about fifteen minutes of walking, Reason saw Jimmy in the woods and signalled him over. The two made their way back to the stagecoach, where Charley had managed to get the strongbox open. When they came in sight, Reason grabbed Jimmy’s rifle and took two shots at Charley. Both his shots missed. Jimmy then took the rifle back and fired two shots. He did not miss. [3] Charley was wounded and fled, bleeding. He left his tools behind, but held on to the gold. Reason and Jimmy went on to the nearest town (the wonderfully named Copperopolis) and alerted the authorities. Jimmy led a posse back to the scene, and there they found the vital evidence, the leather suitcase that Charley had used to bring his disguise to the scene. Inside was a variety of bits and pieces, most notably a handkerchief (or, in some accounts, a shirt cuff) with a legible laundry mark. “F.X.O.7.” The hunt was on.

The wounded Charley made his way across the hills. After about a quarter of a mile he stopped, unable to run any further. He hid the majority of the gold in a rotten log, but hung on to $500 in coin. His shotgun went into a hollow tree, and he bound his wound up with a handkerchief. Charley, as mentioned, never rode a horse so he was well used to long walking. He trekked nearly a hundred miles through the California hills to Sacramento, avoiding people where he could. He encountered one old hunter named Martin, but tried to bamboozle him by asking for false directions. In Sacramento he used some of the coins to get a shave and a haircut, and some more to replace his damaged clothing. He wrote a letter to his landlady to hold his rooms, then caught the train to Reno to lay low for a few days before returning to San Francisco. He stayed in a boarding house the first night, but when he realised his rooms were not stalked out he decided the coast was clear and returned to his regular life. However he did so too soon – on November 12, nine days after the robbery, the Wells Fargo detective, a man named James Hume, [4] and a private detective named Henry Morse he had hired succeeded in tracking down the laundry mark. The mark corresponded to a tobacconist’s shop that also acted as an agent for a laundry company, and the owner recognised the handkerchief (or cuff) as that of “Charley Bolton”. Morse went to set a watch on the address that he was given, but when he returned to the shop to talk to the owner again he was lucky enough to catch Charley coming down the street. “Black Bart” was captured at last.

At first Charley denied the charges, insisting that he gained his money through mining. He knew enough of the trade to pass himself off, but inconsistencies in his story (and evidence found when his room was searched) began to add up. Martin’s identification of him was enough to put him on trial, and at the prospect of a long prison sentence Charley’s nerve broke. He agreed to plead guilty (to that one robbery) and to give up he location of the remaining $4,500 in gold in exchange for a reduced sentence. The judge agreed, and he was sentenced to six years in San Quentin. On November 21, just 18 days after the robbery, he began his sentence. Throughout the trial and in jail he denied being Black Bart or committing any of the other robberies, and denied being Charley Bowles (his real name having been found on a bible in his room). He wrote several letters to his wife Mary, however, despite this denial.

In prison he worked in the hospital, at first as a clerk and then later in the dispensary. Here he showed a talent for preparing and compounding prescriptions, enough that he considered working in a drug store as a possible career choice after his release. One of his close friends in prison was Charles Dorsey, another stage coach robber. Dorsey escaped in 1887, though he was recaptured 3 years later. On January 21, 1888, Charley was released early for good behaviour. He was mobbed by reporters on his release, as the mystery that had surrounded “Black Bart” still made for a good story. One asked if he would go back to robbing stage coaches, but he said he was through with committing crimes. Another asked if he would write any more poems, to which he replied: “Young man didn’t you hear me say I would commit no more crimes?”

Charley stayed in San Francisco for a month, but he was not happy there. He wrote to Mary, telling her of how the Wells Fargo detectives were dogging his heels. An ad appeared in the personals column, asking Black Bart to get in touch with a PO Box to hear “something to his advantage” – probably an offer to write his life story. Whether Charley contacted them or not, in February he left San Francisco and travelled to the city of Visalia. There, on February 28th, he checked into the Palace Hotel. The next day they found his room abandoned, apart from a suitcase containing food, two neckties – and two pairs of cuffs with the “F.X.O.7.” laundry tag. That was the last time anyone ever saw Charley Bowles for certain. One postscript, however. In 1917 newspapers in New York city published a report of the death of a Civil War veteran named Charles E. Bowles. If this was Charley, he would have been 88. Did the man who had reinvented himself so often reinvent himself one last time, as a respectable old time war vet in the big city? Perhaps we’ll never know.

[1] According to some versions of the story, the driver was “John Shine, later a US Marshall and State Senator”. While I don’t know about his name or whether he was a US Marshall, I can say that there was never a State Senator named John Shine.

[2] And not the 18th century pirate Bartholomew Roberts, who didn’t get the “Black Bart” nickname until the Welsh poet Isaac Hooson chose it as the title of a ballad about him in 1936.

[3] A later account written by Reason 20 years later disputes this, and claims that he fired all four shots. However he agreed to let Jimmy take the credit in exchange for getting all of the reward money.