Blood on the Leaves | Ep. 2 | The Abduction of Hanns Martin Schleyer

Last Week: The Baader-Meinhof Death Night

The body of Max Weinberg lay outside the front door of Apartment 1, Connollystraße 31 in Munich’s Olympic village. Coach of the Israeli wrestling team at the 1972 Olympics, he was the first person executed by a faction of the Palestinian Liberation Organisation operating under the name of Black September.

For two days, September 5th and 6th, while the games carried on, Black September held twelve members of the Olympic team hostage, during which time a retaliatory attack by Weinberg led to his execution, though it also enabled one athlete to escape.

A symbol of resistance, Weinberg was put on public display as a statement to preface their demands sent to the Israeli government, which were as follows: Israel would release 234 Palestinian political prisoners, while in addition, two other guerrillas, Andreas Baader and former-editor-in-chief of konkret, Ulrike Meinhof would be released from Stammheim Prison in Stuttgart.

These two West Germans were pivotal figures within the Red Army Faction, or the Baader-Meinhof, Baader one of its original leaders, Meinhof its spokesperson. Why they were named on this list, an Israeli secret service investigation later suggested was because the organizer of the assault was a man named Abu Hassan who had trained Baader-Meinhof members at a Palestinian Liberation Organisation camp in Jordan.

The only problem was that the plan failed rather quickly. Israeli Prime Minister Golda Meir was firm in his response to the demands of Black September. Under no circumstances would Israel negotiate with Black September. Were they to move even an inch, then it was plausible hostage-taking would repeatedly be used by terrorist cells in the future.

On the evening of the 6th, after the athletes were beaten, tortured and forced to watch the castration of teammate Yossef Romano, a weightlifer, who died in the village, the remaining nine were brought by the eight Palestinian radicals to Furstenfeldbruck airport. The intention was to fly to Cairo. However, when two of Black September’s men were about to board the aircraft, German snipers opened fire.

In response, Black September turned on the athletes. Using Kalashnikov machine guns, they executed every single member of the team, before responding to the German assault. One police officer and five Black September members were shot dead on the scene. The other three managed to escape.

Hours later, writing from her prison cell, Ulrike Meinhof hammered out a manifesto entitled, The Action of Black September at Munich – Towards the Strategy of the Anti-Imperialist Struggle. Attributed to, but not approved by the RAF as a whole, Meinhof stated that her Palestinian comrades had set an example for West German radicals to follow. She wrote,

‘The comrades of the Black September Movement have brought their own Black September of 1970 – when the Jordanian army slaughtered more than 20,000 Palestinians – home to the place whence that massacre sprang: West Germany, formerly Nazi Germany, now the centre of imperialism. The place from which Jews of Western and Eastern Europe were forced to emigrate to Israel, the place from which derived its capital by way of restitution and officially got its weapons until 1965. The place celebrated by the Springer press when they hailed Israel’s blitzkrieg of June ’67 as an anti-communist orgy…’

Fellow inmate Gudrun Ensslin labelled the work a piece of ‘crap’, but Meinhof was surprisingly accurate in her observations. It was not Meir’s staunch refusal to negotiate that set the standard of the 1970s. Instead, it was Black September’s use of hostages as a bartering chip, which proved the more influential move in West Germany.

June 2 Movement

At 8.53am on the 27th of February 1975, an affiliate group of Baader-Meinhof known as the June 2 Movement abducted Peter Lorenz of the Christian Democratic Union while he was campaigning in the West Berlin Mayoral elections. A conservative whose slogan was ‘More vigour brings more security’, he disappeared seventy-one hours prior to the election, when a four ton truck drove in front of his Mercedes, while a Fiat came at him from behind. When the attackers stepped out of their vehicles to seize Lorenz, one used a broomstick knock out his driver, before he was then dragged into another car parked down the road.

A Polaroid was released one day later, declaring Peter Lorenz a prisoner of June 2 Movement and the demand was for the Bonn Government to free Horst Mahler of the RAF, along with five members of June 2. Accompanied by a short apology, the communiqué read, ‘To our comrades in jail, we would like to get more of you out, but at our present strength we’re not in a position to do so.’

The state response was nowhere near as firm as that of the Israelis. If anything, the Bonn government were happy to comply, because, as one former editor of both konkret and Der Spiegel Stefan Aust speculated, ‘No one accused or convicted of murder was on the list’.

It only took a week for the negotiations to be finalized. The state agreed to release all of the prisoners, except Mahler who refused his freedom. The other five liberated guerrillas were given 9,000 DM and a flight to South Yemen, and while the entire incident was handled rather peacefully, it revealed one major issue in West Germany’s Internal Security. They had literally shown themselves to have zero preparation in the event of such an emergency.

Reflecting on the government’s decision, Chancellor Helmut Schmidt would later express his disappointment with how things were handled, saying,

‘They took it for granted that the prisoners should be exchanged for the hostage Lorenz. I agreed to that myself, but next morning I realized it was a mistake; it simply invited repetition of the same manoeuvre.’

Like Meinhof, he too was correct. Not only did the incident give June 2 extensive media coverage, it also exposed a major weakness on the state’s part. Their miscalculation made hostage taking the new go-to strategy and while there were no immediate fatalities, in the space of the next few years, four people would be murdered at the hands of various names included on that list, amongst the dead being Federal Prosecutor Siegfried Buback.

The Big Get-Out

Skipping ahead a couple of years to the fifth anniversary of the Munich massacre, and Baader was still sitting in his Stammheim cell, eager for the RAF’s Second Generation to secure his freedom. In that time, all members of the RAF on the outside had ceased virtually all attacks related to their revolutionary cause. Instead, the best part of their effort was devoted to securing the release of their incarcerated comrades.

There was a great sense of urgency to repeat what June 2 had achieved. Two members had already died in captivity. Holger Meins had succumbed to a hunger strike in 1974, after prison guards manipulated his daily intake of calories during the force feeding process to accelerate his rate of starvation. Ulrike Meinhof had been found hanging in cell 719 on May 9th, 1975.

Baader had stressed continuously it was inevitable that he and his fellow prisoners would to end up the same way soon. Yet, despite these two deaths, there was reason to be optimistic. If the RAF could handle one hostage situation nicely, then the armed struggle could resume. The only question was whether those on the outside were actually competent enough to reach the negotiations table.

Auntie Hamburg and Uncle Jurgen

July 30th, three weeks after the two-year trial of Baader, Raspe and Ensslin concluded, each handed a life sentence, Jurgen Ponto, former advisor to the South African apartheid regime and chairman of Dresdner Bank, and his wife Ines Ponto were sitting out on the porch of their thirty room suburban villa in Oberursel. Having just finished packing for a holiday in Rio de Janerio, they were expecting a guest to drop by at some point during the evening. This visitor was Susanne Albrecht, a sister of Jurgen’s godchild.

Twenty-six years of age, Susanne was from an extremely wealthy family. Privately educated, she was a graduate from the University of Hamburg and her father was a maritime lawyer. These days, she works as a language teacher in a Bremen primary school. Add to this the fact that she came bearing a bouquet of wild roses and really, one would think she was a delightful young woman. There seemed little suspect about her, even after she had visited the house a few weeks earlier to catch-up with ‘Uncle’ Jurgen’s daughter, casually pondering life’s small questions here and there, such as the house alarm system, the whereabouts of the cleaning staff and the number of dogs the Ponto’s kept.

She had, in her early twenties gravitated towards the RAF, so sick was she ‘of pigging out on caviar and smoked salmon’. While in college, she became interested in Marxism and soon after completing her degree she would share flats with both Karl Heiz Dellwo and Silke Maier Witt, Second Generation RAF members, the kind of people middle-class parents would not like you to be hanging around.

Growing to become a prominent far-left activist, who campaigned for an improvement in the prison conditions for RAF prisoners, by the time she paid a visit to the Ponto’s, she was no longer the charming young middle-class girl they had once known, although her floral blouse said otherwise.

She arrived at the gate with company and the family chauffeur sent this news up to Ines.

‘There are two more young people with her’, the chauffeur said.

‘What do they look like?’ asked Ines.

‘Very respectable’, he replied, eyeing up the RAF’s new leader, Brigitte Mohnhaupt, and Christian Klar.

Jurgen came out to greet them, before ushering them out onto the terrace. Accepting Susanne’s gift, he then went looking for a vase. While doing this and quite unexpectedly, Klar barked, ‘You come with us – this is a kidnapping.’

‘Are you out of your mind?’, Jurgen responded in disbelief.

Klar fired once. Mohnhaupt, five times. Jurgen went down, taking two bullets to the chest and three to the head. Landing on the living room floor, the trio ran out to a car occupied by Peter Jurgen Boock. By 18:30, Jurgen was dead.

Subsequent to this, Boock and Mohnhaupt fled for Baghdad to plan ‘the Big Get Out’. Meanwhile, back at home, the West German police began a search for Albrecht and two associates, her former roommate Maier Witt and Siegrid Sternebeck, a trio collectively known as the Hamburg Aunties. There was however, no official response by anybody in the RAF relating to the murder.

Two weeks passed before Susanne went public by signing an RAF communiqué that addressed the incident. Dated August 14th, she wrote ‘on behalf of a RAF Commando’,

‘In a situation where the BAW and state security are scrambling to massacre the prisoners, we haven’t got a lot of time for long statements.

‘Regarding Ponto and the bullets that hit him in Oberursel, all we can say is that it is a revelation to us how these people, who launch wars in the Third World… can stand dumb-founded when confronted with violence in their own homes…

‘Naturally, it is always the case that the new confronts the old… [That] means the struggle for a world without prisons confronting a world based on cash, in which everything is a prison.’

As this panned out, the inmates’ own efforts to improve their collective living situation had reached a dead end too. On September 2nd, Jan Carl Raspe issued a communique calling for all RAF prisoners to end their fifth hunger strike with immediate effect. Their second in 1977, Raspe’s order followed an attempted intervention by Amnesty International, in which the organization called for the state to ‘establish more humane prison conditions’.

Claiming the strike had ‘broken down, because “the situation had hardened”’, by which he meant their treatment had become increasingly draconian, Raspe wrote,

‘[F]ollowing the attacks against… Ponto, the authorities had received instructions from above to make example of the prisoners.’

‘… As a result, the prisoners have broken off their strike on the 26th day- so as not to facilitate the murderous plan.’

With few options left on the table, there was still one major operation in the works. The rumoured ‘Big Get-Out’ had officially commenced.

60 Seconds

September 5th, 1977, Cologne, and at 17:25, Dr. Hanns Martin Schleyer was being driven by his chauffeur, Heinz Marcisz from the German Employer’s Association to his home. Sat in the backseat of a Mercedes 450 SEL, he was accompanied by a twenty-year old police officer named Roland Pieler. In tow was a car carrying two other officers, Reinhold Brandle and Helmut Ulmer.

For two years, the Bonn government had classified Schleyer as a level three security threat, stating that an ‘assault cannot be excluded’ in his case. Indeed, a brief overview of his backstory can easily explain why they were concerned about his well-being.

Born in Baden on May 1st 1915, Schleyer was raised in a Catholic conservative family. In his teens a member of Hitler Youth, his interest in National Socialism strengthened once he went to the University of Heidelberg to study law. Then, on July 1st, 1933, he joined the SS and became a Second Lieutenant.

Noted for being highly antagonistic towards any fellow student reluctant to discriminate against Jewish people, during his time in college, he became the leader of a National Socialist student movement, before becoming a full-fledged member of the Nazi party in 1937.

When the Second World War commenced, he was drafted. He spent several months on the western front, his time there cut short when an injury forced him to be re-stationed in Prague. It was there, while leading a Czech student body that he met the German economist Bernhard Adolf, who led the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia. Their meetings ended with Schleyer being hired as a deputy advisor to its industrial association, but by the end of the war, he fled Prague once the 1945 Uprising started.

While in flight, he was captured and held in an Ally POW camp. There he would remain for three years.

He had however, managed to negotiate a light prison sentence, apparently because he understated his role in the party. So by 1948, he was already being released and repatriated. The next year, he had become secretary of the chamber commerce at Baden-Baden and by the early 1950’s, he had used his networking skills to get onto the board of directors.

Remaining in this position until the late 1960’s, his failure to become chairman of the board pushed him to get involved in employers’ associations, while also, becoming President of the Confederation of German Employers’ Associations and the Federation of German Industrialists.

When we meet him, travelling west along Friedrich Schmidt Strasse, he had just recently been bumped up to a level one threat.

Being chauffeured along what was his daily route, on this day the small convoy passed a Volkswagen bus before turning right onto Vincenz-State, a one-way street, where there was a woman pushing a baby-blue pram.

Suddenly out of nowhere, Marcisz was forced to brake. A yellow Mercedes had come at them from the opposite direction. Simultaneously, the woman pushed her pram out onto the road. The yellow car swerved, mounting the pavement and Schleyer’s convoy was trapped.

Then, the police escort accidentally rammed straight into the back of Schleyers’ Mercedes.

There was a brief pause.

Two figures emerged from the Volkswagen wearing balaclavas. Following them was the woman and a third man who emerged from the Volkswagen.

A Colt pistol was produced followed by a Heckler and Koch automatic, a Makarov pistol and a PM 63 machine pistol. They opened fire.

The group unloaded seven rounds on Schleyer’s Mercedes, killing both Pieler and Marcisz instantly, while the escort vehicle took 60 cartridges. Ulmer and Brandle responded by returning the fire. One of the gunmen, Willy Peter Stoll leapt onto the car’s bonnet and emptied an entire round into the pulverized windshield. Ulmer went down after spending three rounds, Brandle after eight. The pair incurred a total of twenty bullets between them.

With Schleyer the sole person still alive, he was taken from the car and dragged into the bus, where the pram pusher, Sieglinde Hofmann injected him with an anaesthetic. Not sixty seconds since she had deployed the pram, the VW driver, Boock, jammed on the accelerator and they shot off, chased by several witnesses who lose sight of them quickly.

At 17:33, the incident was phoned into a police station and the first unit arrived on the scene two minutes later.

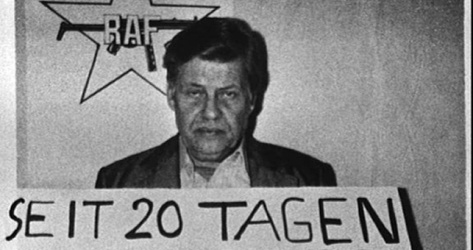

At 22:40, that night, the first communique was put out:

‘The federal government must take steps to ensure that all aspects of the manhunt cease -or we will immediately shoot Schleyer without even engaging in negotiations for his freedom.’

Signed by the Red Army Faction, the assault was credited to the Seigfried Hausner Commando, which consisted of Boock, Stefan Wiesniewski, Hofmann and Stoll. In addition, other members with suspected involvement were Adelheid Schulz, Angelika Spietel, Friedericke Krabbe, Rolf Heissler and Silke Maier Witt.

Sixty seconds, the execution of their assault was frighteningly sharp, owing to meticulous planning for months. It was not so much that the security surrounding Schleyer was flawed, quite far from it. The Commando however, had been capable of pinpointing the few exact pores in an otherwise watertight guard. They knew the vehicles were not armored and that the officers were carrying standard automatic handguns, hence, they chose to arm themselves with an arsenal which would have a clear upper-hand in the inevitable exchange of fire.

His route back and forth was repetitive, easy to map, but especially ideal for an ambush since the majority of the drive was down one-way streets. Furthermore, the fact that the vehicle carrying Brandle and Ulmer trailed behind Schleyer was perfect. The two officers would be at a clear disadvantage were an assault to be carried out from the front. They had managed to convert Schleyer’s protection into a projectile, and to this day, the operation remains on various curriculums relating to counter-terrorism.

Kontaktsperre

Stating that the Stammheim inmates were somehow responsible for orchestrating the assault from within the walls of the Dead Wing, the Bonn Government passed a measure known as Kontaktsperre, or the Contact Ban, which was implemented on October 2nd. In her biography, Remembering the Armed Struggle: Life in the Baader-Meinhof, Margarit Schiller (an inmate at Frankfurt Prison) described the ban, by saying,

‘All contact to the outside and on the inside was cut off for us prisoners. Without any legal basis, [the] ban was enforced for… approximately one hundred prisoners… [We] were no longer allowed recreation,… radios,… newspapers or… letters, we were no longer allowed to see our lawyers or any other visitors. We were totally isolated. Nothing from the outside world made its way through to us… [N]obody on the outside heard anything about us. This created a space for the state to do whatever it wanted.’

Continuing, she wrote,

‘Almost all of my personal belongings had been taken from me, my notes, books, writing materials, clothes, the radio, archived materials… There was no music any more. Although there was almost nothing left in my cell, it was still searched on a daily basis… At least once a week, I was taken into an empty cell where I had to strip naked in front of two female warders and change my clothes.’

It was ‘cell-control’, Schiller said, based on the idea that the prisoners were in some way responsible for Schleyer’s abduction. The Stammheim inmates however, had lost the ability to contact with people on the outside since mid-August, so was it actually possible for them to have had any role in influencing the Commando?

According to the Minister of Justice Hans Jochen Vogel, it was not. Speaking on Italian television six months later, he had this to say:

‘We didn’t even assume that at the time and there was nothing to confirm that that could have been the case.’

All of this information brings to mind more than a few major questions: Given how Schiller described the treatment dealt out to each and every prisoner, how could two pistols, a knife and a severed cable go unnoticed for fifteen whole days? If there was no means of maintaining contact with one another, how could a pact be agreed upon, and more importantly, since the only report of events in Mogadishu to reach Germany while the inmates were still alive was via a radio broadcast at 00:38, how could they have possibly known?