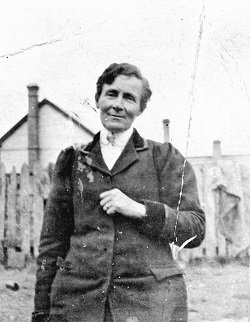

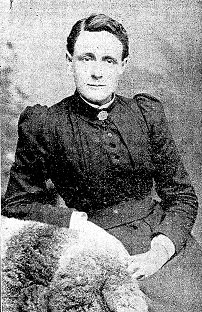

Amy Bock, the Feminine Bridegroom

Amy Bock was born in the city of Hobart in Tasmania, the Australian island subsequently a state, in 1859. She was the second of six children. Her father, Alfred, was a photographer, a trade which kept the Bock family on the move through her childhood. Amy showed an interest in amateur dramatics at an early age, something her father encouraged. In 1874 the family settled in Melbourne, possibly due to her mother Mary Ann’s poor health. The following year Mary Ann passed away in a mental asylum. Following this tragedy both Amy and her father moved away from Melbourne – he to New Zealand where he would marry again, she to the east into the rural area of Gippsland. There she stayed near Merriman’s Creek with a man named John Woods, who seems to have been a family friend. Her mother’s sad end earned her much sympathy, and she was smart enough to gain an education and put it to good use as a school teacher.

Amy got a job at the state school in Maryvale, a small town which had sprung up around the railway from Melbourne to the big town of Sale. She was well liked by her pupils and their parents, but she was soon to ruin her life. In May 1884 Amy was arrested, on charges of fraud. The newspaper at the time says that she was initially arrested for the acquisition of two gold watches from a jeweller in Melbourne. She spun him a tale (backed with a letter claiming to be from her brother) that one of the watches was to be presented to a man retiring from her brother’s club, and got them both to show him and have him choose. (Not an unusual arrangement in those days.) When she failed to return to the store, the proprietor had her summonsed by a lawyer, and when she failed to appear he contacted the police. Since Amy had used her real name they had little trouble tracking her down. When they investigated further they found that Amy was responsible for multiple other bad debts round the city. This included two carriages she had purchased on credit and then sold on. Other items listed at her trial included a piano and multiple pieces of furniture. On Friday 23rd of May she was arrested and taken to court, where she was described as:

[R]ather below the medium height, and of very quiet, unassuming appearance…[H]er features were pinched in and deathly pale, and that she was thin and sickly, as though suffering from serious illness.

She had been ill in bed when arrested, and her case was remanded to allow a doctor to examine her (for both her physical and mental health). Before she could be brought back to trial, however, she fled the country. She had an open invitation from her father since his remarriage in 1882 to move to New Zealand, and this she did. Her father returned to Australia three years later in 1887, but Amy could not return with him.

In New Zealand Amy now settled into a familiar pattern that would repeat multiple times over the next twenty years or so. She took a position as a governess to a family in Auckland, who found her absolutely charming. They were less charmed a few weeks later when she was caught defrauding them. In court she wept, pretending that this was her first offence, and invoked her mother’s illness as the reason for her compulsive actions. This may well have been a true defence – Amy’s motives for theft over the years doesn’t ever seem to have been financial gain. In fact, most of the money she stole went on buying people presents, often the same people who she had defrauded. Her actions, at any rate, do not seem to have ever been malicious.

Amy worked at various jobs over the years, almost all in service. Cook, governess, housekeeper or companion – her charm and friendly nature won her many friends, few of whom could believe it when they found out she had stolen from them. Among her more legendary exploits was a spell on holiday in Dunedin, visiting a woman she had made friends with on a ferry. One day while the family were out at a picnic, Amy stayed home with a migraine. It was not until bailiffs turned up a few weeks later that the family realised that she had invited a money lender over while they were out and taken out a loan secured with their furniture. That time she evaded justice, but sooner or later she was always caught. And then when she was released, she’d turn around and do it again. It was a compulsion, a sickness that the people of the time either couldn’t treat or just didn’t care to. The worst part may be that Amy was well aware of her illness – on one occasion she said:

God knows best, and I am quite content to abide by His will, and I still hope and pray that He, who only can, will in His own good way and time free me from this terrible disease which causes me such misery, and others, too, through me. Only He knows the horror I have lived in all these years.

Amy wound up in court in 1885 on charges of fraud, but the charges were dropped – her accusers were sorry for the girl, who they thought was not in her right mind, and merely wanted to show her the seriousness of her actions. It was not a lesson that would stick. Her first prison sentence was for a single month the following year for buying goods on credit and absconding. The following year she was sentenced to six months in a reformatory, where her charm and intelligence led to her being offered a job as a teacher to the other prisoners – but her attempt to forge a letter from a non-existent aunt to aid her parole hearing led to both it failing and the loss of her privileges. In 1888 she spent two months in jail after an elaborate scheme of false letters and family emergencies went awry. In 1890 her criminal records got her the maximum sentence for fraud, three years, after she mortgaged her employer’s piano. Less than a week after her release in 1892 she was arrested for stealing a watch and sent back for another month. During her time in and out of jail she became associated with the Salvation Army. As usual, her charisma won her more than a few friends, all of whom could barely believe it when she was accused of trying to defraud the organisation. They never charged her, doubtless from a Christian spirit of forgiveness.

In 1895 she was placed (whether voluntarily or involuntarily is unknown) in the Magdalene Laundry in Christchurch. She disappears from the records for seven years, but by 1903 she had either left or escaped. Her horizons had broadened to real estate scams, but her execution left something to be desired. An attempt to raise money via bank loans (under a fake name) for a non-existent poultry farm purchase saw her back in prison until 1904. In December of that year an attempt to alter a cheque saw her get another two year sentence (bringing her total prison sentences, though not time served, to sixteen years and two months – over a third of her life). In 1908 she pawned her employer’s furniture and went on the run, attempting to throw investigators off the scent with a web of fake letters and fantasy scenarios. Though they would probably not have anticipated her actual scheme for avoiding detection – reinventing herself as a sheep farmer named Percival Leonard Redwood.

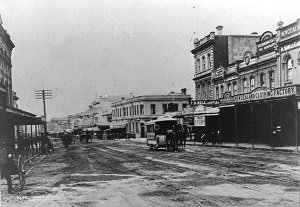

Amy’s masquerade as Percy may simply have started out as way to avoid detection, but it soon metamorphosed into something a lot more complicated. Percy was taking a vacation from his ranch to the small town of Port Molyneux in Otago. Thirty years earlier it had been a bustling port, but a catastrophic flood diverted the course of the river, turning the area into swampland. Now it was just another sleepy backwater, with less than a hundred residents. The sort of place where a rich outsider like Percy turned heads. And one head that he turned was that of Agnes Ottaway, his landlady’s daughter.

It’s hard to know exactly why Amy, in her guise as Percy, proposed marriage to Agnes. Some modern people theorise she was a lesbian, or a trans man, and so see this as a genuine attempt at romance. However this doesn’t seem to match with her previous or later actions, nor with her later apparent intention to escape the whole situation. Others see it as some grand scam, something Amy intended to turn to her profit. Though how she intended to do so is an open question. Perhaps it was as simple as her lies getting away from her, and matters progressing beyond her control. However it was, the die was cast. The date was set. And so on the 21st April 1909, Agnes Ottaway and Percy Roundwood were joined as wife and husband.

Several in the community had the suspicion that Percy, this strange small outsider, was not quite what he seemed. Most of this was caused more by Amy’s financial shenanigans rather than her gender, as she resorted to her usual schemes to ensure that Percy could live up to his supposed wealth. It was this which led the Ottaway family to forbid Percy from consummating the wedding at first, though whether this came as a relief or disappointment to Amy is impossible to say. Instead Percy was put in a room with one of his new relatives the night of his wedding, and the groomsman became very suspicious when his roommate climbed into bed fully dressed in his wedding suit. Still, Percy claimed that his mother would be arriving the following week with enough money to cover his debts, and so the honeymoon was set to begin the following Wednesday. But by Sunday a chance discovery of women’s clothing in one of Percy’s lodging rooms led to questions being asked, the police being contacted, and photographs being shown. Soon the constables came calling to Port Molyneux, and Amy was arrested once again.

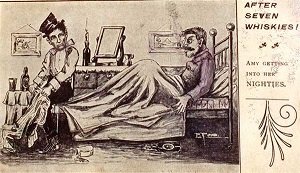

The press, unsurprisingly, leapt on the story. To some of the reporters she was a familiar character, and one paper even led with the headline “Amy Bock’s Latest Escapade”. All her earlier adventures and run-ins with the law were dragged out, and every paper had to have a picture of her. In fact, Amy became such an ubiquitous topic of conversation that one paper even printed a song about how sick they were of hearing of her. Her debtors cashed in on the craze and auctioned off her wedding ring and suit to recoup some of their losses. (She also sold some things to cover her legal fees, though her lawyers decided to donate the money to Agnes Ottaway.) Most of the public treated it as a grand joke, and even the Ottaways didn’t seem to hold that bitter a grudge. When Amy went to trial they even put in a petition for her to be treated lightly. Despite that, however, the judge sentenced her to two years on charges of forgery, fraud and of making a false statement under the Marriage Act. He seems to have recognised that Amy suffered from some form of illness though, and did say that she should be psychologically assessed in prison.

One month later Amy was back under the consideration of a court. Agnes and Amy had been legally married, after all, and so the marriage had to be annulled. Agnes put in the petition, and while Amy was not present the matron of the gaol was. On her assertion of Amy’s gender, the marriage was annulled. The most interesting part of the case (and one which I have sadly found no further details on) is a remark made by Agnes’ lawyer. He referred to an earlier case that had come before the judge several years before, one the report in the paper refers to as “Lance vs Trequair”. This was a similar case where a woman who had married a woman was appealing for annulment, but in that case the pair had been living together for eight years. Sadly he goes into no further detail on this pair. Agnes was married the following year to a widower named Thomas Gilmour.

Amy was released in February 1912. Her sentence had ended in December 1910, and she had spent the following fourteen months undergoing “reformatory treatment”. The court’s evaluation of her as a “habitual criminal” meant that she could have been held indefinitely, known in Australian slang as “a Kathleen Mavourneen” after a line in a popular ballad:

It may be for years, and it may be for ever.

She was only released when they decided that she was unlikely to reoffend. Amy did her best to disappear into obscurity in the tiny coastal town of Mokau, though the newspapers still kept an ear to the wind for any news of her. Her marriage to Charles Christofferson, an immigrant from Sweden, saw some mention in December 1914. Most of the papers were careful to include that on this occasion, Amy was the bride. Amy did her best to live an honest life, but she was still unable to resist her compulsions. Her marriage was strained by her habit of borrowing money and never paying it back, and in 1917 she landed back in court charged with theft. In light of her long period of honesty, she was fined rather than imprisoned. Her misfortune continued, as Charles turned out to be a drunk who abandoned her and moved back to Sweden, leaving her destitute. Still, Amy managed to find work as a servant once again and for seventeen years she managed to keep on the straight and narrow. Her last appearance in court, once again for obtaining money through false pretences, came at the age of 71 in 1931. Her old friends the Salvation Army spoke up for her, and she was granted a release on probation provided that she retire to their home for the elderly in Parnell. There she died, her passing unremarked by the media who had covered her life so avidly, in 1943.

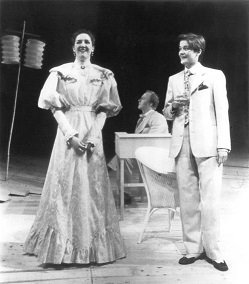

Amy’s is a curious case, and one that aptly illustrates the prejudices of her era. The clear mental issues that drove her to commit her crimes went almost unremarked at the time, dismissed as simple “habitual criminality”. On the other hand, her challenge to social convention through donning male attire became a fixation in the media, and her name continued to be invoked for decades after the case with any case involving cross-dressing being labelled “Another Amy Bock”. As late as 1920, “Amy Bock” was a common fancy dress outfit. Amy’s name also seems to have become an insult applied to any man of feminine appearance – one dock worker who constantly greeted another with the phrase “Hello, Amy Bock” was actually fined £3 for behaviour “calculated to cause a breach of the peace”, while a long-haired preacher in Christchurch was “questioned by ribald persons concerning his relationship with Amy Bock”. Still, it was her challenge to the narrow definition of marriage of the day that was the most troubling aspect for some. Over twenty years later, one paper even felt compelled to rewrite history and deny that Amy’s marriage had needed to be dissolved. In this way, despite it being unlikely that she was either trans or a lesbian, Amy became a symbol to many in those camps. It was in this vein, for example, that the playwright Julie McKee wrote The Adventures of Amy Bock, a play which was selected for Sundance and later taken to Broadway in the late 90s. And so perhaps the final chapter in Amy’s story came on the 19th August, 2013, when equal marriage became the law in New Zealand. Perhaps it wasn’t what Amy herself would have sought out, but for the generations of women whose stories were inextricably linked with hers, it was a final vindication.