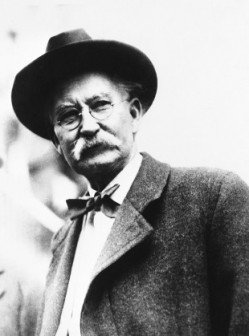

Albert Fall, American Politician and Criminal

Albert Bacon Fall was born in 1861 to a poor family in Kentucky. His early schooling was patchy at best, and non-existent at worst, as he was forced to work in the local cotton processing factory to support his family. This damaged his lungs, so he was forced to move East in search of drier climes. He passed through Oklahoma and Texas, and eventually settled in New Mexico, a notoriously lawless territory. Though his formal schooling had been lacklustre, Fall was an intelligent man and had taught himself a lot from books in his spare time. He was able to find work as a schoolteacher and as a drugstore clerk, though he lacked qualifications for either job. In 1883 he married a girl from Texas, and in 1891 he passed the bar and became a lawyer. Around the same time, he finally managed to break into politics.

Albert Bacon Fall was born in 1861 to a poor family in Kentucky. His early schooling was patchy at best, and non-existent at worst, as he was forced to work in the local cotton processing factory to support his family. This damaged his lungs, so he was forced to move East in search of drier climes. He passed through Oklahoma and Texas, and eventually settled in New Mexico, a notoriously lawless territory. Though his formal schooling had been lacklustre, Fall was an intelligent man and had taught himself a lot from books in his spare time. He was able to find work as a schoolteacher and as a drugstore clerk, though he lacked qualifications for either job. In 1883 he married a girl from Texas, and in 1891 he passed the bar and became a lawyer. Around the same time, he finally managed to break into politics.

Fall had run for a seat in the New Mexico House of Representatives as a Democrat in 1888, but he had been defeated by the Republican candidate Albert Jennings Fountain, a former Colonel in the Union army who had previously been President of the Texas Senate. Fountain was also a lawyer, and his most famous case had been (unsuccessfully) defending Billy the Kid. Fountain and Fall became enemies, and in 1890 when Fountain stood for re-election then Fall managed to defeat him. As a result of this rivalry, Fall aligned himself with Fountain’s enemies, chief among them Oliver Lee, a rancher with a reputation for gunfighting. Lee had come to New Mexico to try to set himself up as a rancher, but had soon fallen foul of the local powerbrokers, including Fountain. At the time politics in New Mexico were deeply intertwined with economic power and occasional outbursts of violence, such as the Lincoln County Range War twenty years earlier. In the mid 1890s, accusations began to fly that Lee was engaging in cattle rustling. Whether the accusations were true or not is hard to say, as though Lee claimed that this was merely a trumped-up charge designed to aid his legal murder, there is some evidence that his hired hands had a history of such behaviour. What is true is that Albert Fountain went to the city of Lincoln in February, 1896 to collect a set of indictments for Lee’s arrest, and never came home again.

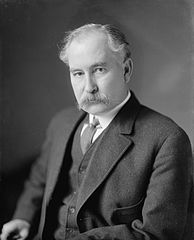

Fountain vanished on his way home, along with his eight-year old son Henry. Though their bodies were never found, their fate was hardly in doubt. Their wagon was found abandoned, along with two pools of blood. Henry Fountain’s handkerchief was in one of the pools, while his father’s rifle was missing. The outlaw Tom Ketchum [1] was known to be operating in the area, and at first he was officially a suspect, but the investigation never went far from Lee. The only problem was that Lee was officially a lawman – Fall had become a judge (though he was forced to resign in a vote-fixing scandal), and had got Lee and two of his men positions as deputy lawmen. Fall had also become wealthy and powerful through representing mining firms and investing in mining. New Mexico’s governor, William Taylor Thornton [2] decided to bring in an outsider to handle the investigation, legendary outlaw hunter Pat Garret. Garret spent several years gathering evidence, but he waited until 1898 to present his case against Lee, as Fall had managed to become attorney general of New Mexico in 1897. A warrant was issued for the rancher’s arrest, but he went into hiding. Garret pursued with a posse, and there was an armed stand off in which one of Garrett’s deputies was killed. Lee and his companion, James Gilliland, escaped. However they realised that the death of his deputy meant the Garrett would very likely not be taking prisoners if he caught up to them, so they turned themselves in with one condition – that Garrett wouldn’t be allowed to take charge of them.

The trial took place in Hillsboro, the county seat of Sierra County. Fall was the counsel for the defence, and he had the deck loaded against the prosecution from the start. The lack of bodies made a murder conviction difficult enough to obtain, but missing and intimidated witnesses, along with an intimidating armed presence of Lee supporters, ensured that a “Not Guilty” verdict was hardly in doubt. The trial sent out a clear message to Fall’s opponents – though he was no longer attorney general, he still ruled the courts. In 1908, Garrett was killed in a dispute over grazing rights. Lee’s brother-in law paid the killer’s bail, and Fall defended him in court. Though the evidence pointed to an ambush, Fall managed to get a verdict of self-defence returned.

In 1912 New Mexico officially became a state, and so it sent its first senators to Washington. There was considerable competition for those seats, but Fall was determined to win one. As the Republican party had gained in ascendance, Fall had switched allegiances. Though this made it possible for him to win one of the seats, it meant that he was not that popular with his fellow party members. Fall made an alliance with Thomas Catron, who was part of the “Santa Fe Ring”, to ensure the two would win both of the Senate seats. The Hispanic community in New Mexico were especially enraged by this underhanded behaviour, as it meant that there was no chance of one of them winning the seat, though the rest of the Republicans were not pleased by it either. Fall’s re-election in 1913 was declared illegal by the governor, who forced a re-vote, but Fall won that as well. In 1918 he was re-elected once again, despite lackluster campaigning. The lackluster campaign, and probably the votes, can be explained by a personal tragedy – he had lost two children in the Spanish Flu epidemic. Catron had died in 1916, but by then Fall had his own new allies in the Senate. Fall was a member of the Ohio Gang.

The Ohio Gang has a somewhat misleading name. Not all of its members came from Ohio, for starters. The name comes from the locus of the group – Warren G. Harding. When he came to the Senate in 1914, he brought with him a lot of his supporters from his home state. As the original men fell away and were replaced, the name still stuck to the grouping, and Fall soon became one of its leading lights. In 1918 Teddy Roosevelt was considering running for re-election as president, and Harding was his choice for vice president. When he decided not to run, his election manager Harry Daugherty managed to convince Harding to put his name forward as the Republican candidate. Harding didn’t think he had much chance of winning, but in a field dominated by intense personal rivalries he became the “least worst choice” for most of the delegates. In the following election one key decider was the newest voting block – women. Harding had supported women’s suffrage in the Senate (as had Fall), and they repaid him with the White House. The Ohio Gang had taken the Capitol.

Fall was appointed Secretary of the Interior, a position which put him in charge of the country’s natural resources. On the surface, it was a relatively sensible appointment – Fall had experience with mining from his New Mexico lawyer days. In practice it would turn out to be a serious mistake. Fall was heavily at odds with the conservationist movement in the Senate, and so they were quick to rally and defeat his plans to open Alaska to wide scale mining and deforestation. They also blocked his plans to bring the National Forests under the Department of the Interior, they took it as a clear attempt to open them up for exploitation. Fall would have to look elsewhere for opportunity, and he found it in the Naval Reserves.

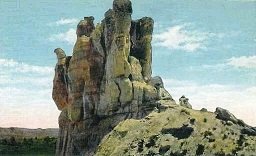

At the time the US navy maintained several oil fields as a private source of supply. The President signed an executive order to transfer the control of the three largest fields to Fall. The fields were the Elk Hills and Buena Vista Oil Fields in California, and the Teapot Dome Oil Field in Wyoming. Fall secretly awarded the production rights to Harry Sinclair of Mammoth Oil and Edward Doheny of Pan American Petroleum. The secrecy was actually legal, and Fall justified it under the claim that publicising the fields would make them a target in wartime. The lack of bidding was also legal under the rules of the time. The leases were extremely favourable to the companies, but that was also perfectly legal. Less legal, however, was the $500,000 in bribes that Fall accepted from the two men. Unfortunately for him the director of one of the companies who had hoped to bid on the rights wrote to his senator, John B. Kendrick, and Kendrick introduced a resolution to investigate the deal. A committee was formed, and the investigation began.

Fall’s initial tactic was to over-respond to the committee, drowning them in documents. He resigned from office, but argued that he was justified in handing out the production rights in this manner because the reserves were surrounded by other private fields. As such the fields needed to be worked, because leaving them unused would result in their oil draining into the surrounding fields. As he described it:

“Sir, if you have a milkshake and I have a milkshake and my straw reaches across the room, I’ll end up drinking your milkshake.”[3]

Though Fall seemed to have an answer for everything, he had forgotten one detail – one of the bribes had come not as a gift but as a loan, an interest-free one from Doheny for $100,000. Fall’s own party also had the knives out for him – Harding died in August of 1923, and his vice-president, Calvin Coolidge, knew that he would have to act decisively to avoid his chances for re-election as President being destroyed by the scandal. He appointed two special prosecutors, a Republican and a Democrat, to investigate what had become known as the Teapot Dome scandal, as well as demanding the resignation of anyone even slightly implicated in it (such as Harding’s former campaign manager, now attorney general, Harry Daugherty). This, combined with the Democratic Party’s own ties to the oil industry, was enough to secure him victory in the 1924 election.

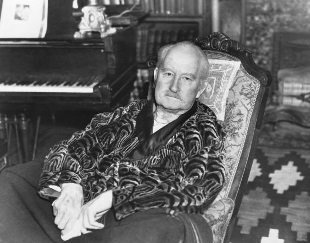

The investigation and trial wound up dragging out past the end of Coolidge’s term in office, and it was 1929 before a verdict was reached. Absurdly, Fall was found guilty of accepting a $100,000 bribe from Doheny, while Doheny (who had appeared for Fall’s defence) was found innocent of offering the same bribe. In fact, Doheny not only got off scot free, he foreclosed on Fall’s ranch in Wyoming for non-payment of the loan and left him destitute. Sinclair was also found not guilty of bribery, prompting one report to declare “You can’t convict a million dollars.” However he was found guilty of jury tampering (having hired detectives to follow them home) and contempt of court, and sentenced to nine months in prison. He served six, and then returned to the presidency of Mammoth Oil and his millionaire lifestyle, none the worse for wear.

In contrast Fall was ruined by the scandal. He was sentenced to a year in prison, but was released after nine months due to ill health. He returned to New Mexico in 1932, where he attempted to resume his business interests, with limited success. In 1935 Doheny’s company tried to evict him, claiming ownership of his ranch and home under the terms of the loan that had been made to him. Fall fought them in court, and was able to hang on to his house, and 100 of his 750,000 acres. The protracted legal action took its toll though, and in 1942 he was admitted to hospital, where he stayed until his death in 1944. He had been the big fish in the little pond of New Mexico, but it had left him ill-equipped to swim with the sharks. His legacy was to become a byword for scandal, and his lasting contribution to America was not what he achieved, but what was done to prevent others repeating his crimes.

Images via wikimedia and Casper Star Tribune

[1] Known as “Black Jack” Ketchum because he kept getting mistaken for another outlaw, “Black Jack” Christian. As logical a reason for a nickname as any.

[2] Who was no stranger to corruption and violence, having taken personal charge of the investigation into my great grand-uncle’s murder a few years earlier.

[3] This quote inspired the 2008 movie There Will Be Blood, where it is used to great effect.