Fear of a Black Picture | The History Behind Spike Lee’s Do the Right Thing

“What will cause the riot?” wrote Spike Lee in his diary back in 1989. “Take your pick: an unarmed Black child shot, the cops say he was reaching for a gun; a grandmother shot to death by cops with a shotgun; a young woman charged with nothing but a parking violation, dies; a male chased by a white mob onto a freeway is hit by a car… the script is evolving into a film about race relations. This is America’s biggest problem.”

The script in question was Do the Right Thing, a tragicomedy that emerged from Lee’s contempt for the American judicial system and its incompetence when serving justice to the perpetrators of racial hate crimes during the 1980’s. His third feature-length film, this signified the moment when Spike Lee became an intimidatingly outspoken media figure, politically charged and no longer just Black Woody Allen.

Having earned modest commercial and critical success for 1988’s School Daze, Lee’s next objective was to create a work of fiction that might honestly assess the extent to which the US had progressed since Lyndon B. Johnson signed the Civil Rights Act of 1964 into law. Twenty-five years had passed. But, if anything, racial prejudice had not disappeared from American society. It had simply evolved, surfacing in the grey areas of politics and law enforcement: situations wherein the person, accused of committing a hate-crime could defend their actions by arguing that the perceived prejudice was merely that, and highlighted only by persons psychologically damaged, i.e. embittered black citizens bent on retribution for past grievances.

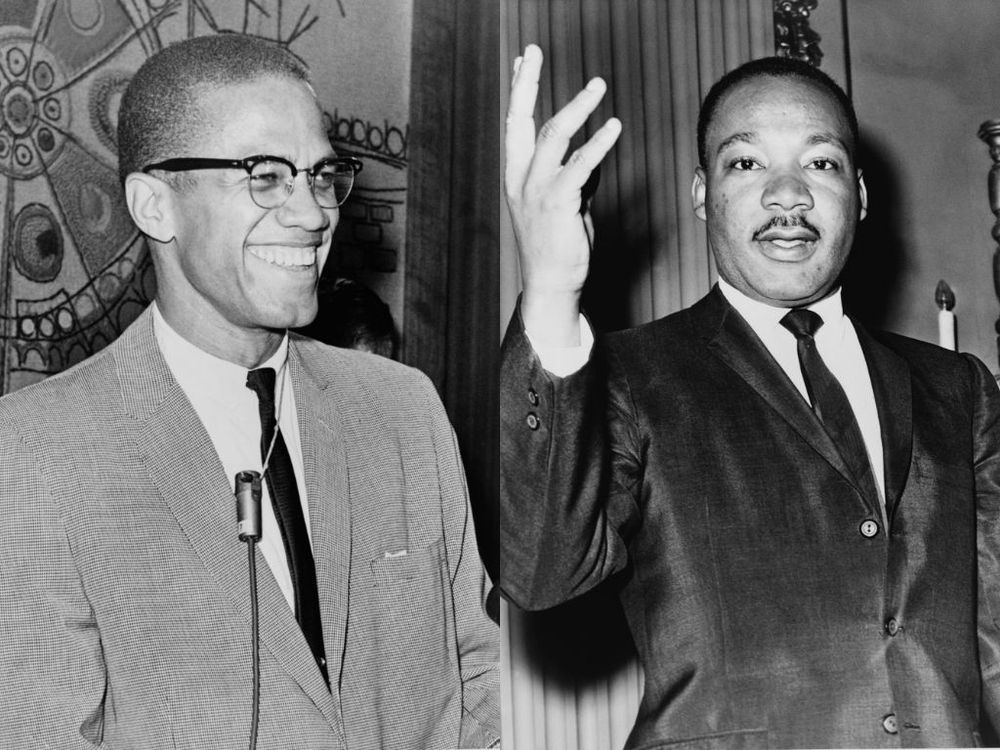

On paper, the United States of America was color-blind. However, in actuality, ethnic relations in New York City were eroding at an accelerating rate, the outcome of which was a spike in racially motivated crimes and widespread indifference towards the impoverished suffering of minorities in areas like Harlem, the Bronx and Brooklyn. In this climate, Lee took it upon himself to ask whether it was still possible to adhere to Dr. King’s philosophy of pacifism in order to survive as a black person in New York. Or was it now a necessity to adopt Malcolm X’s philosophy of intelligent self-defence and kick back when kicked at?

By dwelling on this matter, emerging on the side of X, he hit a sore point in various critical spheres, often being classed as a dangerous provocateur, a rogue and race-monger. Do the Right Thing frightened many in this regard, such sentiments being evident from the get-go, when he gave a press conference at the Cannes film festival on May 19th, the 64th birthday of Malcolm X. Repeatedly pressed to defend his views, while sporting a t-shirt honoring the late-activist, Lee justified himself to anxious interviewers by saying:

“If you don’t use self-defence, you’d be annihilated… Both [the] philosophies [of Malcolm X and Dr. King] can be appropriate, but in this day and age… I’m leaning towards the philosophies of Malcolm X.”

The philosophy of King, he continued, “had its time.”

“There are still times when it is appropriate, but when you’re being beat up… I don’t think young black America is going to turn the other cheek and say ‘Thank you Jesus for hitting me on the side of the head with this brick.”

Do the Right Thing, as a meditation on these two diverging philosophies was, however, not merely a reflection of his own opinion. It was explaining a collective shift among marginalized and frustrated minorities. Weaving into the fiction a slew of actual hate crimes, which had shocked New York in previous years, Lee constructed DTRT as a hypothetical situation wherein a black community reacts aggressively to the next hate crime wrought upon their community.

[iframe id=”https://www.youtube.com/embed/-fXLFfRWSJ0″]

A swathe of film critics and political commentators however were dismissive of its function as a warning sign grounded in historic fact, labeling it instead as agitprop written by a belligerent middle-class filmmaker. John Kroll, in Newsweek, called Do the Right Thing “dynamite”, which would provoke “young urban audiences- black and white”. David Denby, writing for New York, also vocalized his concern, suggesting “parts of his audience” might go “wild” after seeing this “celebration of violence”. And, Joe Klein, in Time, went even further by comparing Lee to the five young men accused of raping a jogger in Central Park on April 19th, speculating that these two events would be the next major hindrance to the mending of ethnic relations in New York City.

Yet, despite these anxieties concerning the apparently volatile nature of certain “parts” of Lee’s audience, the summer of ‘89 was notably free of rioting. As a matter of fact, the anticipated explosion came three years later, but it was not due to any Spike Lee “joint”. It was the brutal beating of Rodney King by members of the LAPD, which launched the Los Angeles Riots, and as this became clear, Lee was heralded as a “prognosticator”. He had diagnosed the collective state of tension was destined to snap at any moment, and for this reason, the legacy of his film is twofold.

Released in America twenty-seven years ago, on July 21st, 1989, Do the Right Thing remains pertinent a study on the race question in post-Civil Rights America, especially given the state of racial disharmony in the United States today. But at the same time, as an agenda piece, conceived with a pointed political purpose, it is an important historical document, which shone light on the actual state of New York City at the turn of the decade.

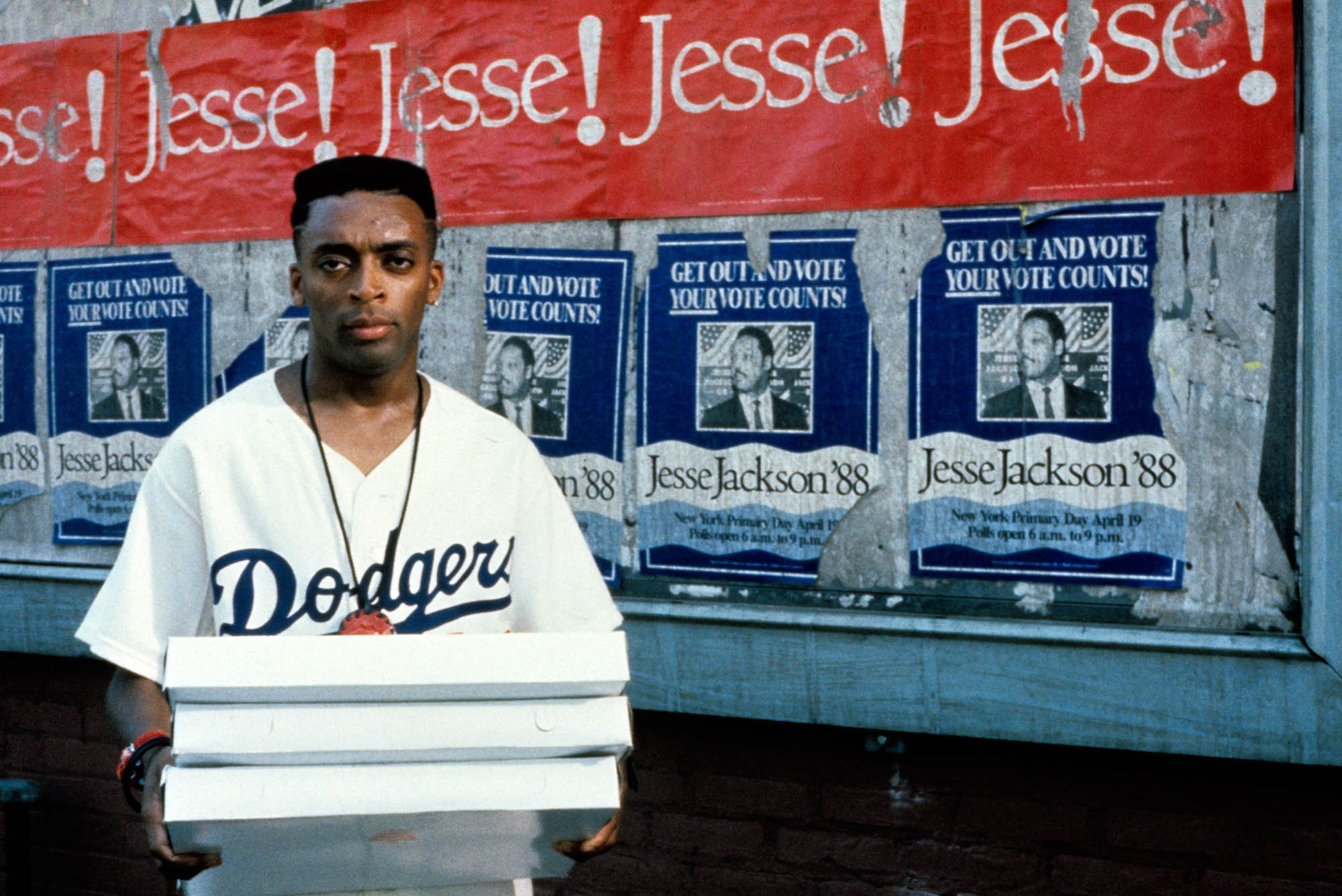

Set in Bedford-Stuyvesant, a Brooklyn neighborhood on the cusp of gentrification, during July of 1989, both the release of the film and the story itself were selected to focus on the upcoming New York Mayoral election due to take place on November 7th.

At the time of its cinematic debut, Ed Koch had served as Mayor of New York City for three terms (twelve years), while the threat of a fourth loomed. A critic of fellow Democrat, the Revered Jesse Jackson, Koch was labelled “the chief architect of racism” in New York and Lee made little secret of his desire to oust him from this position by demonstrating how fraught the city had become as a result of his negligent attitude towards black citizens. Hence, the main story was written as an amalgamation of the many hate-crimes, which had shaken the city whilst Koch had held office.

Told by-and-large from the perspective of a pizza-delivery boy named Mookie (played by Lee), the story looks as the problematic relationship between his employers, the Italian-American Fragione family who own Sal’s Pizzeria, and Mookie’s African-American friends, who have become agitated as a result of the staff’s bigotry. In particular, one customer known as Buggin’ Out has grown extremely irate, after he notices the lack of any “brothers” on the restaurant’s 100% Italian-American Wall of Fame. Sickened by this lack of diversity, he stages a protest, demanding all black people boycott the pizzeria.

His anger only captivates one person, a boom-box carrying teen known as Radio Raheem, who was banned after enraging the owner, Sal, by blaring Public Enemy’s ‘Fight the Power’ at full volume while on the premise. The pair, teeming with anger by sundown, decide to act, and enter the pizzeria after closing-time in order to protest their treatment.

[iframe id=”https://www.youtube.com/embed/Kj9SeMZE_Yw”]

Initially a deafening verbal back and forth, it is the presence of the boom-box (still playing ‘Fight the Power’) that pushes Sal beyond his limitations. Exploding in a tirade of racial insults, Sal seizes a baseball bat from behind the counter and proceeds to beat the holy living hell out of the ghetto blaster.

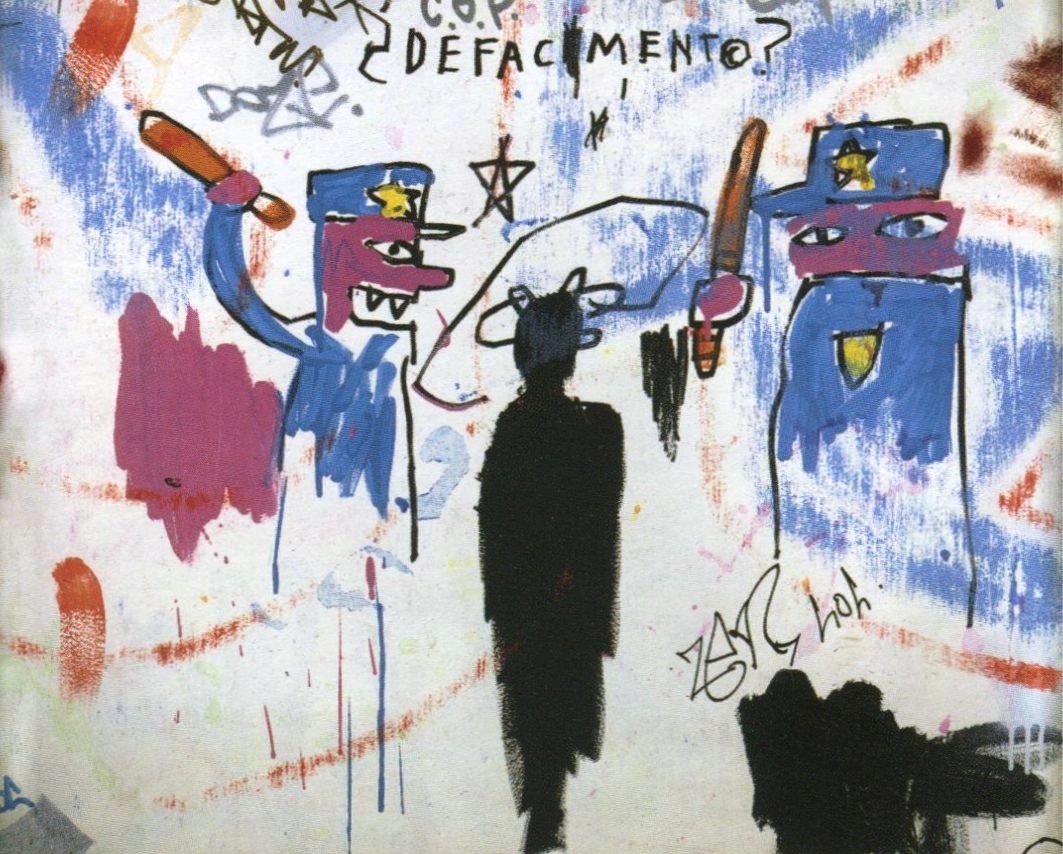

A brawl ensues. The police come and naturally, their immediate instinct is to go straight for the black men. Placing Raheem in a choke-hold, which results in his death, as the reality of the situation dawns, an emotionally exhausted Mookie acts out. Airing his grievances by throwing a trashcan through the window of Sal’s, he sets off the riot, which culminates in the fiery destruction of the property.

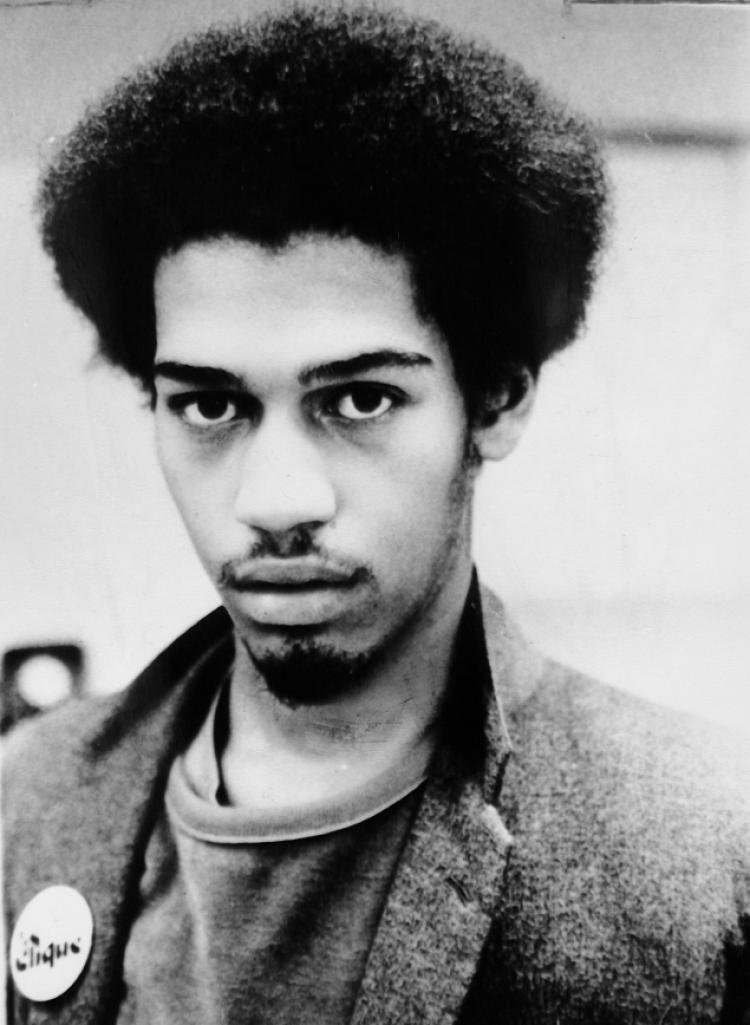

It was not however, simply the onscreen death of Radio Raheem, which provoked the community to act. Subtly, Lee noted that the explosive climax had been brewing for many years, this being made apparent when a voice can be heard screaming, “They did it again… just like Michael Stewart.” Stewart was not a fictional character though.

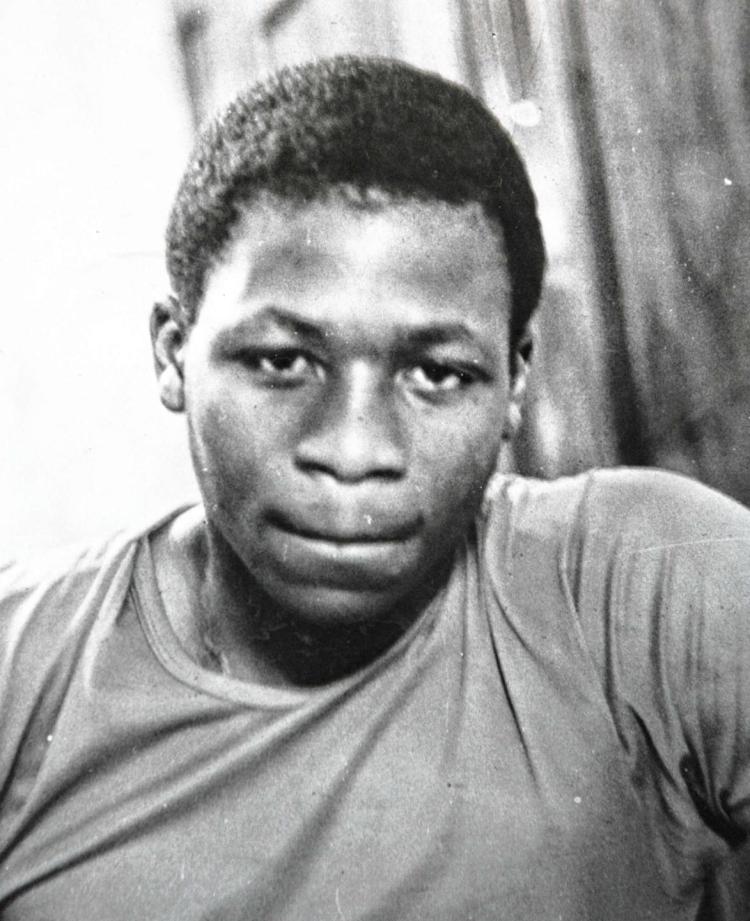

Michael Stewart was twenty-five years old when he died as a result of similar police brutality. On the night of September 15th, 1983, at approximately 2.30am, he had been down on the L-train platform under First Avenue when he inadvertently set off a chain of events, which would eventually culminate in his death.

A street artist, while waiting to board a train bound for Brooklyn, he passed the time by producing a marker in order to tag one of the walls with the letters ‘RQS’. However, in the process, he caught the attention of one Officer John Kostick, a member of the now-dissolved New York Transit Police department. Handcuffed, Kostick recalled Stewart admitting defeat, and saying simply, “Hey man, you got me”. Then as the pair waited for a transport van, Stewart was alleged to have attempted an escape.

Tripping as he rushed up the station’s staircase, a struggle would ensue between the pair until he was placed in the police van. Driven to a police station on Union Square at the intersection of East 14 Street and First Avenue, as he was unloaded from the back, the noise from the ordeal woke 23 students in a Parsons School of Design dormitory. At this point, Stewart was “hogtied”, and Kostick claims he had to be wrestled to the ground. According to a court report from 1985, Stewart was turned on his back then:

“The [unidentified] officer, by grabbing Stewart’s clothing, pulled the upper part of Stewart’s body off the sidewalk. With his other hand, the officer hit Stewart in the head… Immediately thereafter, the officer released his grip on Stewart’s clothing, thus causing Stewart’s head to drop to the concrete sidewalk.”

Stewart was said to have called for help. One Parsons student, Rebecca Reiss in her testimony recalled him shouting: “Oh my God, someone help me, someone help me” and “What did I do? What did I do?” However, Ms. Reiss and her fellow alumni were unable to identify how officers were treating him exactly. Furthermore, they could not say which officers struck him, and specifically whether they were kicking, punching or choking Stewart with a Billy-club.

Thrown back into the van, by 3.30am he was admitted to Bellvue Hospital unconscious and without a pulse. Doctors did manage to restart his heart, but, he was comatose and remained in this state for thirteen days before he eventually died.

“[T]hat’s where we got [the] Radio Raheem stuff”, said Lee in later years. “That is the Michael Stewart choke-hold. Except we didn’t have his eyeballs pop out like Michael Stewarts did”. This detail, though absent from any available reports, Lee highlighted, claiming that police and those examining Stewart “greased his eyeballs and tried to stick them back in the sockets.”

What the autopsies did reveal, despite this alleged cover-up, was that Stewart had suffered heart failure and his body showed significant bruising, particularly around the facial area. As a result of these findings, the State Supreme Court brought six of the offending officers to trial, the proceedings officially commencing on May 28th, 1985.

Presided over by Justice Jeffrey N. Atlas, three officers- Kostick, Henry Boerner, and Anthony Piscol- were charged with “criminally negligent homicide”, while another three- Susan Techky, Henry Hassler, and James Barry- were found guilty of perjury before the grand jury. But, since “no witness was able to identify a specific officer who might have delivered the blows, the defendants were accused not of striking Mr. Stewart, but of allowing him to be beaten in their custody.”

Eventually, on November 24th, 1985, after five months on trial, the six accused transient officers were acquitted. This verdict, reached by an all-white jury, Stewart’s family attorney, Louis Clayton Jones deemed a “farce.”

“All the players happened to be white. The six defendants, the six defendants lawyers, the two prosecutors, the twelve jurors, the judge and even every court officer in the well of the courtroom was white. The only black person there was the victim and he was unable to testify, unfortunately.”

Mayor Koch would defend the jury’s conclusion by observing that one could not criticize a group that had been in deliberation for seven days. Nevertheless, on March 27 1987, he called for an additional investigation into the case. The outcome of this inquest infuriated an even greater many, since only one of the eleven officers connected with the case faced departmental charges. This “loss of faith” in the judicial system, though was not the only case which Lee sought to highlight as he wrote the script.

On October 29th, 1985, Eleanor Bumpurs, a 66-year old arthritic woman was due to be evicted from her apartment in the Bronx, having fallen four-months behind on her rent. Naked at the time of her eviction, she refused the housing workers entry, first by throwing a pot of boiling lye at them, before threatening those who entered with a 10-inch knife.

Authorities attempted to subdue her with a Y-shaped bar and a plastic shield as she repeatedly tried to thwart their advance. Members of the Bumpurs family would however defend her, refuting such claims by insisting that she would have been physically incapable of assaulting the workers owing to her pre-existing heart-condition and arthritis. Contrary to this argument, John Elter, a former-officer, one of the twelve on the scene, would testify that she had made repeated stabbing motions, motivating one Officer Stephen Sullivan to use his shotgun as a means of defense.

Officers attempted to prove her mentally unsound, justifying the actions of Officer Sullivan as the sole option possible at that stage. Hence, he fired two shots. New York Police Department commissioner Benjamin Ward, the first African American to hold this position, reported to Ed Koch that shot number one had “apparently missed”. Police reports claimed Officer Sullivan had only fired his shotgun once. However, the autopsy on Mrs. Bumpurs’ body revealed that she had been hit by two blasts.

The first blast struck her right hand, tearing it off. Two witnesses, one unnamed social worker and Sgt. Vincent Musac estimate then that there was a three second pause, almost the exact length required to eject the first empty cartridge and load a new one, before Sullivan fired again. This shot proved fatal, striking her in the chest. Ward went on record to defended the actions of Sullivan at this point, insisting that he “did what the patrol guide said”, but regardless, Officer Sullivan was tried for second-degree manslaughter.

On April 12th, New York State judge, Justice Vincent A Vitale dismissed this indictment, as evidence brought against the accused was deemed “legally insufficient”. On Vitale’s ruling, Officer Sullivan commented proudly by announcing, “I’m very happy, ecstatic”, before responding to a journalist who asked whether he would still have shot Mrs. Bumpurs, his answer being a simple: “Yes, I would”. Again, Benjamin Ward stood by Sullivan, saying, “The majority of police officers will be supportive of the court decision and will feel as I do that this was right”, while Ed Koch went on to assure New York Times readers, “We learned from that tragedy”.

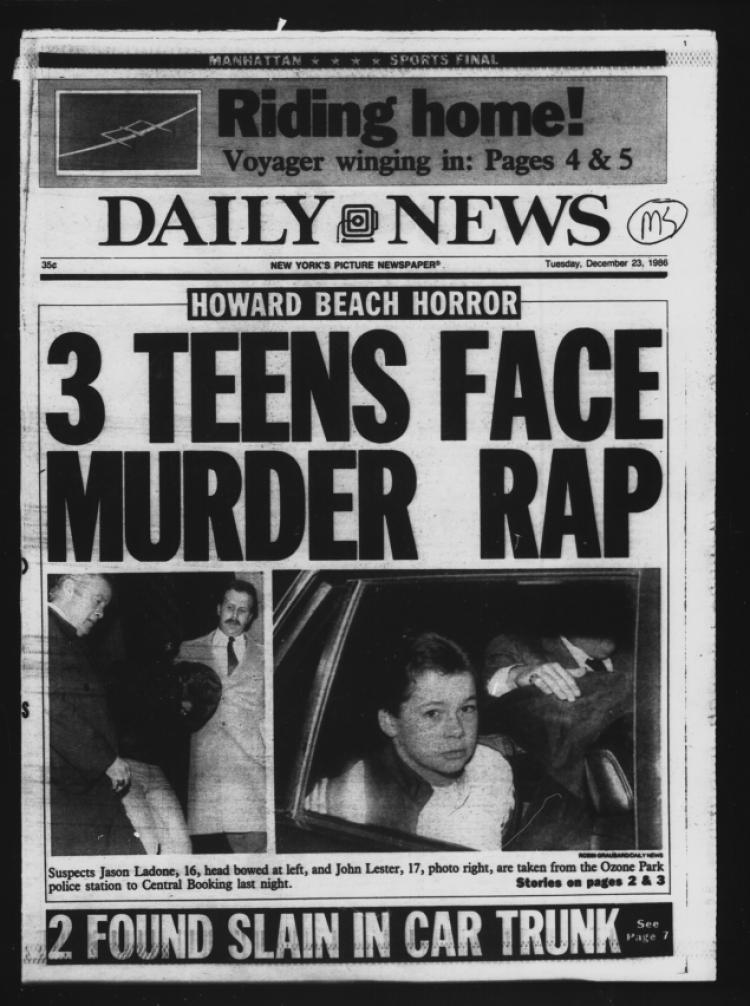

The words of Citizen Koch were of course short lived, with Lee highlighting this point by having the looting crowd chant “Coward Beach” after the fictional NYPD drive Buggin’ Out and Raheem away from the scene of the crime. What he was referring to here was an incident, which took place on December 20th 1986, when four black youths, Timothy Grimes, Cedric Sandiford, Michael Griffith and Curtis Sylvester were approached by a gang of predominantly Italian-American youths in Howard Beach, Queens. The gang initially shouted racial slurs, demanding the group leave their “territory” immediately. However, owing to the fact they were in Howard Beach because their car had broken down, the four men did not have much of a choice, and so they went to at pizzeria on Cross Bay Boulevard. It was while they were dining, that the group of twelve white males returned. Only this time, the gang were armed with baseball bats, tire irons and tree branches.

Griffith and Sandiford were beaten severely during the confrontation. Griffith, bloodied and disoriented, then made an effort to escape, but in the process of doing so, accidentally stumbled out onto a highway. There he was struck by a passing motorist Dominic Blum, the son of an NYPD officer, and as a result of his injuries, he died on the scene. Sandiford on the other hand, was apprehended by police and treated as a suspect. Refused medical treatment, he then was made retell his version of events multiple times until sun came up.

In reaction, the Reverend Al Sharpton arranged a series of protests in Howard Beach, Carnarisie and Bath Bay. At the same time, a number of black figureheads across the state called for a one-day boycott on all pizzerias. The latter action was widely mocked and Lee included it in Do the Right Thing to highlight how, in its absurdity, it began to create profound rifts within black communities in the following days and weeks. Howard Beach signified a point of major disillusionment, both in terms of how ineffective it revealed African-American political leaders to be, and because of how poorly the NYPD reacted to the incident once it was made public how they had treated Sandiford. Benjamin Ward was widely condemned as a “puppet of the white power structure”, and as the case went to trial, the verdict unleashed only greater anguish.

On December 20th, 1987, a jury found three quarters of the principal defendants guilty of second-degree manslaughter and first degree assault. They were also however, found innocent of inciting a riot and attempted murder. One of the assailants, Michael Pirone had all of his charges dropped, while several members of the mob were handed startlingly light sentences, namely community service.

The fragmented state of racial affairs, once the verdict was delivered was not attributed to the actions of the violent white teenagers, or the questionable conduct of any authorities. Far worse a rap was dealt to New York’s black communities, with columnists, such as the New York Times’ Michael Myers blaming the culture of intolerance on exploitative “black extremists” who sought to heighten the climate of hatred. Victimized and then blamed for expressing their dismay, Henry Cisnero, when describing the Los Angeles riots, summed up the snowballing rage aptly by observing, “The white hot intensity that became Los Angeles was the combination of smoldering embers waiting impatiently to ignite for a long time.” The riot was inevitable, and though Lee was seen as attempting to kickstart it himself, in reality he was diagnosing the situation, and showing the likely outcome of these numerous injustices.

Do the Right Thing was the diagnosis of a era rapidly descending into crisis, backed up by historical fact, and then validated by Lee’s prescience. In spite of the warning signs though, those same mistakes remain uncorrected. Unfortunately, due to this fact, it has yet to lose any of it relevance twenty-seven years later. Contrary to the initial backlash brought against it by people who felt Lee was longing to inspire mobs to revolt, it stands as a dynamic story about the inevitability of violence in any place where a minority endures oppression.

As a document from a specific time, it would prove culturally significant because it went as far as to explain why the streets of Los Angeles exploded back in 1992. And as each subsequent tension has given rise to far uglier reactions, such as those seen in Baton Rouge and Dallas, it continues to help us fathom why people like Micah Xavier Johnson and Gavin Long act in the way that they did. Those situations are inevitable, and since Do the Right Thing first emerged, the riot has evolved to such extents that one can now draw parallels between current affairs and the bloody slave revolts led by men such as Nat Turner and Denmark Vesey during the 1820’s and 30’s. Do the Right Thing may have been intimidating. Indeed, it may still be so. But it echoes a sentiment contained within the old slave hymn about Turner, and in the end, continuous denial of America’s race problem can only make the following verse an even greater reality down the line:

“And your name it might be Caesar sure,/

And got you cannon can shoot a mile or more,/

But you can’t keep the world from moverin round/

Nor ol’ Nat Turner from gainin ground.”