Charlie Peace, Victorian Fugitive

Charlie Peace was born in Sheffield in 1832. His father, John Peace, was a shoemaker by trade, though that was not his first profession. John had originally been a coal-hauler, but he lost a leg in a workplace accident. One story is that for some time he found work as a lion-tamer in a circus, but that all came to an end when one of the lions killed his eldest son. He left the circus and settled in Sheffield, where he took up shoemaking. There he raised his family, including young Charles. Charlie was an indifferent student, mostly remembered for his extravagant tomfoolery, and left school as soon as it was legal for him to do so. He went to work at the local steel mill, but at the age of fourteen he was badly injured by an accident in the workplace. Young Charlie spent a year and a half in hospital, and when he left he was left crippled for life, though not so severely as his father had been. [1]

Charlie’s misfortune was cemented by his father’s death around the same time. Quite when Charlie turned to crime as his source of income is difficult to pin down, but in October 1851 he was found in possession of goods that had been burgled from an old lady’s house. Due to his previous good reputation, Charlie was let off lightly with only a single month in jail. On his release he began trying to earn a living as a musician, but this doesn’t seem to have been enough to sustain him. In 1854 he was arrested for burglary again, and this time he received four years in jail. His girlfriend and his sister, who were in possession of some of the goods he had stolen, received six months each. On his release in 1858 he resumed his life of crime. In 1859 he was married to a widow named Hannah Ward, inheriting a stepson named Willie. Soon after the new Mrs Peace was deprived of her husband as he was arrested once more for a burglary in Manchester, and imprisoned until 1864. In 1866 he was arrested again. While he was in prison his wife had a son, and this may have inspired his escape attempt. He used a homemade saw of tin and a makeshift ladder to cut through his cell’s ceiling. A warden entered the cell as he was climbing through the hole, but Charlie managed to get away from him out onto the roof. There he made his way to the governor’s apartments and stole a suit of clothes. The prison was on high alert however, and Charlie didn’t manage to get out before the apartments were searched and he was caught.

By the time Charlie was released from prison in 1872, his son was dead. He was forty years old, and had spent nearly half of his life in prison. Perhaps conscious of this, he seems to have made a serious effort to “go straight”. He started working as a picture framer, and turned out to have a natural talent for the craft. In fact, Charlie always seems to have had a great deal of skill and intelligence, but his own worst characteristics seem to have betrayed him. This time is was not the lure of burglary that destroyed him, but a far more conventional lust. In 1874 he made the acquaintance of Arthur and Katherine Dyson. Arthur was an engineer, who worked on the railroad. Katherine was an American woman, who he had met and married eight years earlier while she was living there. When she met Charlie, Katherine was an attractive woman in her mid-twenties, and the two became close. How close is hard to say – Charlie later claimed that she became his mistress, while Katherine denied it. They did spend a great deal of time together, but at some point in 1875 Katherine tried to break off the relationship. Charlie refused to give up and began stalking her, leading to threats from her husband. Charlie responded by making death threats to Katherine. When Arthur made a complaint against Charlie and had a warrant issued for his arrest, Charlie moved away to Hull. He continued to stalk and torment the Dysons, though he was also active in even more nefarious pursuits. Perhaps driven back into the illicit by the thrill of his pursuit of Katherine, Charlie had resumed burglary, and worse.

On the night of the 1st August 1876, Charlie was attempting to break into a house in Manchester when he was spotted by two policemen. He made a run for it, but one of the policemen, named Nicholas Cock, managed to catch him. Charlie had a revolver and used it, shooting the policeman and making his escape. Nicholas later died of his injuries. Luckily for Charlie, the murder was pinned on a local man named William Habron. William had been arrested for being drunk and disorderly a few days earlier by Nicholas, and had threatened to “do for him”. Furthermore, the other policeman had seen someone matching his description hanging around the area of the murder. A slim thread to hang a man’s life on, and the judge summed up in his favour. However when the jury returned a guilty verdict, with a recommendation to mercy, the judge sentenced him to death. Clearly he felt a cop killer deserved no less. Charlie literally had a ringside seat to this miscarriage of justice – he often attended trials for amusement, and he definitely wasn’t going to miss one for a murder he had himself committed. He later said that he enjoyed the whole thing immensely. Luckily for William, a letter-writing campaign to a local newspaper led the Home Secretary to grant him a reprieve, commuting the sentence to life imprisonment.

Charlie’s feud with the Dysons came to a climax on the 29th November. Charlie had gone to visit Sheffield in order to bring the local vicar what he claimed was proof of Arthur and Katherine’s low moral character. He was in an excited state, having spent the afternoon in a local pub drinking. After the left the vicar, he went to call on friend but the friend was away. Unable to resist the temptation, Charlie went to the Dysons’ house, where he found Katherine in the garden. He tried to compel her to speak to him by threatening her with a revolver – probably the same weapon he had used to murder the policeman. When Arthur came into the yard to confront him, Katherine ran back into the house. She heard two shots ring out, and when she came back out Charlie was standing over Arthur’s mortally wounded body, gun in hand. Charlie fled home, told his mother and his brother what he had done, and then fled back to Hull. Once there he was just sitting down to his dinner when two policemen arrived looking for him. While his wife stalled them he fled out the back and away.

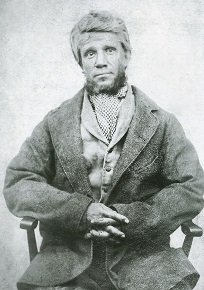

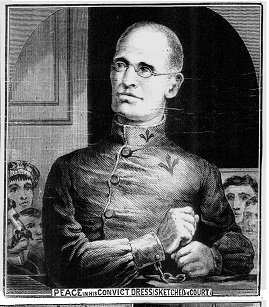

Charlie was now a hunted man. The police issued the following description:

Charles Peace wanted for murder on the night of the 29th inst. He is thin and slightly built, from fifty-five to sixty years of age. Five feet four inches or five feet high; grey (nearly white) hair, beard and whiskers. He lacks use of three fingers of left hand, walks with his legs rather wide apart, speaks somewhat peculiarly as though his tongue were too large for his mouth, and is a great boaster. He is a picture-frame maker. He occasionally cleans and repairs clocks and watches and sometimes deals in oleographs, [2] engravings and pictures. He has been in penal servitude for burglary in Manchester. He has lived in Manchester, Salford, and Liverpool and Hull.

They had overestimated his age by ten years or so, but otherwise it was a reasonable description – at least until Charlie set about changing his appearance. First he shaved off his beard and began dying his hair. Next he took the more drastic step, to conceal his hand injury, of taking to wearing a false arm. [3] Or rather a false false arm, as he wore it over his real one. Still, not even this was enough to protect him. On January 9th Charlie took the most extreme step imaginable to a Yorkshire man. He moved to Nottingham.

In Nottingham Charlie managed to find rooms at a boarding house run by a woman named Mrs Adamson, who conveniently also acted as a fence and “fixer” for Nottingham’s criminal underworld. It was through Mrs Adamson that he first met Mrs Susan Bailey, a 35 year old woman who had separated from her husband. Charlie had stolen a box of cigars, and Mrs Adamson sold them on to Susan (minus a thirty percent commission). Charlie was struck by Susan, and when he had gotten drunk declared his passion by threatening to shoot her if she rejected him. Susan responded sarcastically, and her daredevil demeanour seems to have endeared her to him even more. The next day a sober and contrite Charlie apologised. This succeeded where his threats had failed, and Susan became his mistress.

Charlie spent some time preying on the citizens of Nottingham, though he made a brief return to Hull to visit his wife, stepson and daughter (and for a few revenge burglaries). He was still a wanted man, and the reward on his head increased from £50 to £100. His exploits in Nottingham didn’t escape attention, and the local police were soon on his trail. Eventually they tracked him down to his lodgings, and were shocked to break in and catch him in bed with “Mrs Bailey”. Charlie gave his name as “John Ward”, and managed to persuade them to give him some privacy to get dressed. When they moved downstairs he escaped through a window. Clearly Nottingham was getting too hot for him, and so he and Susan headed south to somewhere a man could easily lose himself – the great city of London.

It didn’t take long for Charlie to establish himself in London. In fact, by Christmas 1877 he was able to entertain his daughter and her fiance as his guests for the festive season. His house at that point was in Lambeth, a poorer district of the city, but he was still able to show them the sights of the big city. His burglaries soon proved profitable enough that he was able to move with Susan to a house in Greenwich, where he rented both sides of a semi-detached house. One side was for him and his mistress, while the other was for his wife Hannah and his stepson who he persuaded to move down from Hull. Greenwich proved too refined for Susan though, and so Charlie moved them all into a single house in Peckham. Of course, he wasn’t going under the name of Charlie Peace, who was a wanted man. Instead he was Mr John Thompson, while Susan was Mrs Thompson. Hannah was a relative living on his charity. Mr Thompson was a pillar of the community, a man with an independent income who supplemented it by dealing in musical instruments, and who was known for his hobby of inventing things. In fact, one of his inventions (a patented device for raising sunken ships) led to him being invited to the House of Commons to discuss it with Samuel Plimsoll, an MP well known for his commitment to improving shipping safety. The only fly in the ointment of his perfect life was Susan’s drinking, as there was always the risk of her giving away his secrets while intoxicated.

It wasn’t Susan that eventually led to Charlie’s comeuppance, however, but rather his own complacency. He had a few close calls throughout 1878, most notably when he met a policeman from Yorkshire in the street. The policeman recognised him, but Charlie was able to outrun him and escape into the crowd. The word was out that Charlie was in London, but it wasn’t just Charlie the police were after. He had made the affluent area of Blackheath, near his old house in Greenwich, his main hunting ground. However he had not learnt from his experiences up north that by creating a hunting ground, he was making somewhere that he could be the prey. The Blackheath Burglar became a priority for the force (not least because he was preying on the “respectable” members of society) and their patrols were stepped up in the area. One of these patrols caught sight of a light appearing in a back window of a house at two in the morning. Two of them kept watch at the back, while one went to the front and rang the bell. This prompted Charlie to flee the building, straight into the two waiting policeman. He had his revolver, and came very close to committing his third murder. Four of his shots went wide (one just missing a policeman’s head), the fifth wounded one of them in the arm. Before he could fire a sixth the injured policeman had managed to beat him into submission.

Though the police knew they had caught the Blackheath Burglar, they didn’t realise they’d also closed out the Peace case – at least at first. Nor did they initially connect their prisoner (described in the report as “a half-caste of about sixty years of age”) with the eminently respectable Mr John Thompson. Charlie was worried about his family, though, and wrote to a friend of “John”’s named Henry Brion. In truth, his family were fine – they had fled the house in Peckham after his arrest, with Susan fleeing to Nottingham and Hannah to Sheffield. The letter to Brion was signed “John Ward”, and appealed for his discretion. When he turned up at the police station and found that Ward was Thompson, and heard what he had done, he naturally told the police everything he knew. That set them on the trail of “Mrs Thompson”. Though they had enough to convict “Ward” (as they called him at his first trial) of burglary and attempted murder, and to sentence him to life imprisonment, they rightly suspected that some greater secret was still to be found.

It was Susan who betrayed the true identity of Charlie Peace, in the end. The police managed to track both her and Hannah down, and Charlie’s mistress was willing to give him up to save her own skin. (She also unwittingly saved Hannah, as the law was that a wife could not be prosecuted for a crime like handling stolen property if she had been ordered to do so by her husband.) Following her revelation, a detective who knew Charlie by sight was sent down to Newgate to identify him. When he picked him out in the exercise yard, Charlie was loaded onto a train and sent north to Sheffield, to stand trial for the murder of Arthur Dyson. Arthur’s widow Kathleen had returned to America after his death, but she was more than willing to cross the Atlantic to visit justice on the man who had ruined her life. Her evidence on the first day of his trial, January 17th 1879, was damning. Charlie must have realised he was destined for the noose.

Charlie was returned to London between hearings, and when he was transported up for the second one he made an attempt to escape from the train. He faked a stomach illness, necessitating the two guards to constantly take him to the bathroom. Eventually they tired of this and at a station they got a quantity of bags that he could relieve himself into and that they could then throw out the window. When they opened the window to dispose of one of these, Charlie made an attempt to dive through it and escape. (He later admitted that this was less an escape attempt, and more an attempt to die on his own terms rather than on the scaffold.) One of the guards grabbed his leg, and the two men struggled while the other guard tried to get the train stopped. Eventually Charlie broke free and fell, and a mile later the guards managed to get the train stopped. When they travelled back up the line they found Charlie lying unconscious where he had fallen, bleeding from a head wound but alive.

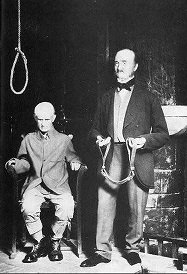

The trial resumed on the 30th January, and Charlie’s solicitor (despite all the evidence against him) managed to mount a spirited defence. With Charlie already serving a life sentence it was clear the only thing to do was to try to keep him off the gallows. His main avenue of attack was to claim that Kathleen and Charlie had actually been in a relationship, that Arthur had attacked Charlie, and that the killing had been in self-defence. Though he did manage to establish that the two had probably been closer than Kathleen had been willing to admit, the evidence of the people Charlie had met that morning showed clear premeditation and the medical evidence showed no signs of any struggle. The judge’s summing up reflected this, as he pointed out that Mrs Dyson’s evidence was not the sole lynchpin of the prosecution. It took the jury only ten minutes to come back and find Charlie guilty of murder, and the judge, without fanfare, passed the inevitable death sentence.

While waiting for his hanging Charlie confessed to the murder of Nicholas Cock in Manchester three years earlier. William Habron was released, and was given £800 in compensation for his time unjustly imprisoned. This, and his penitential demeanour in prison, all excited some sympathy in the public. One person who did not share that sympathy was Kathleen, who said to a journalist:

The place to which the wicked go is not bad enough for him. I think its occupants, bad as they might be, are too good to be where he is. No matter where he goes, I am satisfied that there will be hell. Not even a Shakespeare could adequately paint such a man as he has been.

That may have been somewhat harsh. Though Charlie was a murderer, he had never killed a man in cold blood. He was clearly a man of intelligence and bravery, but the rigid social system of the Victorian era offered no way for the son of a shoemaker to rise beyond the working classes. Yet his eagerness for the criminal life, his swift recourse to violence when provoked, and his lack of remorse at taking a human life all combined to ensure that his end was never going to be a quiet one.

Images via Wikimedia and Murderpedia except where stated.

[1] The exact details of Charlie’s injuries are somewhat sketchy. Most reports give it as an injury to his leg, though a few give it as a hand injury. The latter does gain in some plausibility though by the fact that he did definitely have a crippled hand later in life, while the “permanent limp” the leg injury proponents claim does not seem to have prevented him running fast enough to escape the police on occasion.

[2] A type of printed colour picture.

[3] The hand injury was either the result of the industrial accident in his youth or, according to some sources, the result of an accident with a firearm.