We Do Not Live in a Democracy, But Here’s How We Could

Canadian-born Dubliner and lecturer in international law Roslyn Fuller may have made history in Beasts and Gods: How Democracy Changed its Meaning and Lost its Purpose. These ideas could change the world. The book challenges the assumptions most taken for granted and most effective at keeping powerful people in power. For Roslyn Fuller, “dysfunctional democracy” is not a matter of “how can we fix our broken democracy?” It is a matter of realising that our current system of government is not a democracy, does not operate like one, and is not intended to.

It is taken for granted that for all of our problems, we do fundamentally live in a democratic society. This assumption is grounded in the observation that our country and the vast majority of Western countries have freedom of speech and regular elections. Elections give people a say in how their country is run by choosing the government, and as the government is changed every few years, all you have to do is use your freedom of speech to influence voters. This is how we’re told democracy works. Yet if elections achieved “people-power” as suggested by the Greek root word of ‘democracy’ – demokratia – then why do we often see people angry about what the government are doing, or hear politicians described as “out of touch”?

In her book, Fuller rigorously analyses elections from over 20 Western democracies and finds that elections do not in fact produce results that are free and fair. Her analysis of the first-past-the-post voting system used in the UK, the US and Canada, starkly lays bare how the seemingly straightforward idea of one person voting for one candidate actually leads to utterly random election outcomes that can go against public support and insult the most basic concept of democracy. Many countries have proportional representation in their elections so that political power is divided up closer to the split of the vote. Yet Fuller outlines how these voting systems can still lead to skewing of results, and contends there are further flaws with electoral democracy no matter what voting system you use.

First of all, a parliament of hundreds of people representing millions of people is too small to ever be truly reflective of that population. Politicians typically come from a narrower background dictated by the profile required to be a viable election candidate – financial ability, name recognition, support from a political party, etc.

Secondly, if you do deputise power to a small group of people, those people become targets for powerful interests wanting to influence government policy to their benefit. What Fuller finds is that wealthy corporations influence governments more; most notably through the clear statistical pattern that the best-funded parties and candidates almost always win.

Yet even if there were parties you approved of who got to form a government, they’re not actually obligated to pursue policies the public wants. People may protest but within certain levels of civic unrest governments can ignore protests. Citizens may sign petitions and write to their representatives but they can be fobbed off with stock responses. And even in countries like Switzerland where citizens can call for referendums, money is once again the statistically-strongest influence in determining which side of a referendum campaign wins.

Money gets into you government. Getting into government gives you 100% of the power even if the largest party in government has less than 50% of popular support. This is particularly dangerous for democracy when governments are granted all sorts of powers in negotiating, accepting and enforcing international agreements of which there are a staggering number – the vast majority of which are unknown to the public. These lock countries into pursuing certain policies whatever the make-up of their government is. All it takes is for one government to sign up and they’ll have influenced their country’s public policy for years long beyond their mandate.[pullquote]Money gets into you government. Getting into government gives you 100% of the power even if the largest party in government has less than 50% of popular support.[/pullquote]

Money gets into you government. Getting into government gives you 100% of the power even if the largest party in government has less than 50% of popular support. This is particularly dangerous for democracy when governments are granted all sorts of powers in negotiating, accepting and enforcing international agreements of which there are a staggering number – the vast majority of which are unknown to the public. These lock countries into pursuing certain policies whatever the make-up of their government is. All it takes is for one government to sign up and they’ll have influenced their country’s public policy for years long beyond their mandate.[pullquote]Money gets into you government. Getting into government gives you 100% of the power even if the largest party in government has less than 50% of popular support.[/pullquote]

International agreements tend to cater to the goals of wealthy interests, not just because of their influence on elected governments who form such agreements, but because international organisations like the IMF or even the UN tend to give more say to richer nations over poorer ones. Fuller does not hide her aversion to neo-liberal economic policies as she argues that these are what create inequality within and between nations. While much of her critique of neoliberalism is based on analysis available elsewhere, she brings it home to a crucial point; such policies are decided by very, very, very few people, yet they impact billions of lives for generations.

Fuller outlines how such a set-up for democracy is not compatible with its stated goals which are often so loosely defined. All countries have to do is hold a regular election of some kind and they can be considered a democracy. Yet absent from Fuller’s book is a hint of cynicism. It doesn’t deny positive social change can and does happen. It doesn’t even argue that elections are futile. Roslyn Fuller is running as an Independent candidate for Dublin Fingal in next year’s elections, so she doesn’t seem to think they are. At any rate, those little decisions the government makes every day do affect our lives, so it is important who gets elected. Politicians who lack scientific literacy or harbour bigoted views would be a detriment to public office and may be prevented from taking office by informed voters.

It’s not that democracy isn’t worthwhile; it’s that in its current form democracy is exhausting. You have to work so much for so little reward, competing against the interests of a greedy few who can influence policy much faster than you. With democracy in such a muddled mess, how can Fuller not only avoid a cynical tone but provide a compelling case for optimism? Her historical research into the democracy of ancient Athens does just that.

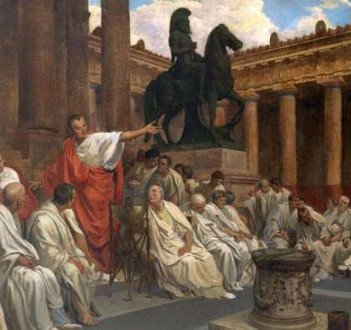

Although for many years they operated with a government run by elected officials, financial collapse led the Athenians to do some serious soul-searching about their mechanisms of government. An Assembly was established to decide all major policy decisions. Membership of this Assembly was comprised not of elected officials, but of any citizen who showed up. The Assembly would meet regularly for a few hours, hear speakers on motions, and vote by a show of hands. Any citizen could participate and was actually paid for showing up (the ancient equivalent of around $30 by Fuller’s calculation).

Although for many years they operated with a government run by elected officials, financial collapse led the Athenians to do some serious soul-searching about their mechanisms of government. An Assembly was established to decide all major policy decisions. Membership of this Assembly was comprised not of elected officials, but of any citizen who showed up. The Assembly would meet regularly for a few hours, hear speakers on motions, and vote by a show of hands. Any citizen could participate and was actually paid for showing up (the ancient equivalent of around $30 by Fuller’s calculation).

If this system of government sounds strange, the strangest thing of all is that it worked. For a period of 140 years, up until around the invasion of Alexander the Great, this was how Athenians passed laws and approved public expenditure. It is precisely because a larger chunk of the population was now involved, and their civic participation was valued and even paid for, that decisions faced high levels of scrutiny. Decisions that passed the Assembly were more likely to have consistent public support. And even if they didn’t, they could be easily revisited.[pullquote]It’s not that democracy isn’t worthwhile; it’s that in its current form democracy is exhausting.[/pullquote]

Athens was a small city of around 40,000 people and no more than 15% of eligible citizens ever attended at one time. Yet that number was still large enough to be broadly representative of the population since each member was bound to be directly or indirectly affected by an issue raised. The number was also large enough that trying to bribe or coerce that many people was just too impractical. Special interests can corrupt a parliament of politicians because it’s relatively easy to target a few dozen politicians who depend on financial support to get elected. However, if decisions are being made by thousands of people from across all sectors of society, the challenge of influencing them sufficiently in your favour is far greater.

But who actually worked in government to carry out the policies decided? Once again, it was in the hands of the people. Civil service jobs in ancient Athens were appointed by a random public lottery. If random selection for such jobs sounds bizarrely prone to risk, keep in mind that is how we, in the 21st century, select people for jury duty. Consider also whether you actually know of a satisfactory explanation of what qualifies a civil servant or elected politician better for the job than the average person.

A citizen in Athens had to volunteer to be considered in this lottery and although there was a small financial incentive for doing so, it would more likely have been a civic-minded person that would apply for a government job without knowing which one they would get. If an official messed up or was corrupt, the Assembly met regularly and could take swift action. Either way, the official wouldn’t hold the job for long so an unsavoury force would have to bribe several officials for any degree of consistency. This combination of a public decision-making Assembly and a randomly-appointed government eliminated any incentive to corrupt government officials.[pullquote] Special interests can corrupt a parliament of politicians because it’s relatively easy to target a few dozen politicians who depend on financial support to get elected.[/pullquote]

A citizen in Athens had to volunteer to be considered in this lottery and although there was a small financial incentive for doing so, it would more likely have been a civic-minded person that would apply for a government job without knowing which one they would get. If an official messed up or was corrupt, the Assembly met regularly and could take swift action. Either way, the official wouldn’t hold the job for long so an unsavoury force would have to bribe several officials for any degree of consistency. This combination of a public decision-making Assembly and a randomly-appointed government eliminated any incentive to corrupt government officials.[pullquote] Special interests can corrupt a parliament of politicians because it’s relatively easy to target a few dozen politicians who depend on financial support to get elected.[/pullquote]

Even if this system of government did work in ancient Athens, one could still suspect that it’s not practical in our modern world. But according to Fuller, it would actually be easier to do this now in large nations of millions of people than the small city-state of a less technologically-advanced civilisation. All it would take is software combining elements of Twitter and Skype so that people could volunteer to speak on webcam and others could comment before finally voting.

Existing software has already been used to practice ‘e-Democracy’ for public budgeting in Porto Alegre, Brazil, and online voting in Estonia. Residents of areas with poor internet access could be facilitated in local libraries or community centres. Physical meetings could be incorporated too if the cost was deemed worthy. Indeed the cost of paying so many people to participate could be weighed against how much we currently pay for politicians, the running of parliaments, and the costly decisions they make through short-term thinking. If such an online meeting was held regularly each week and the agenda was determined by online voting ahead of time, then it should run smoothly as long as there was a secure registration process to moderate abuse and prevent fraud. This kind of online forum would not use anonymity for abusive people to hide behind.

Experiments in deliberative democracy such as AmericaSpeaks in the States, and We The Citizens in Ireland, suggest that when people of opposing viewpoints actually have time to discuss policy in a roundtable format, polarisation can be worked through towards consensus. This sounds like a system of government that would be responsive to citizens’ needs, reduce opportunities for corruption, and bypass the middle-men of elected politicians altogether. Marxists should love it because it’s the real-life practice of “people-power,” and libertarians should love it because diffusing government has made it “small government.”[pullquote]The old form of democracy is tiring, unresponsive and favourable to wealthy interests at whatever the cost to society[/pullquote]

Experiments in deliberative democracy such as AmericaSpeaks in the States, and We The Citizens in Ireland, suggest that when people of opposing viewpoints actually have time to discuss policy in a roundtable format, polarisation can be worked through towards consensus. This sounds like a system of government that would be responsive to citizens’ needs, reduce opportunities for corruption, and bypass the middle-men of elected politicians altogether. Marxists should love it because it’s the real-life practice of “people-power,” and libertarians should love it because diffusing government has made it “small government.”[pullquote]The old form of democracy is tiring, unresponsive and favourable to wealthy interests at whatever the cost to society[/pullquote]

Roslyn Fuller’s platform in her election bid is to introduce online voting to her constituents. She will develop software that will tell her constituents what votes are coming up and ask how they feel she should vote. By voting on that basis, she intends to set a precedent that can be replicated elsewhere. She appeals to the expression of building the new rather than fighting the old.

The old form of democracy is tiring, unresponsive and favourable to wealthy interests at whatever the cost to society. Putting energy into building this new form of democracy could demonstrate how unfit for purpose electoral democracy has become. We could be witnessing the start of a transformative era in human history – one of real democracy and real people-power.

Images via commons.wikimedia.org