From Panel to Projection Booth |2| – The Comics Code Authority

Eoin Rogers continues his bi-weekly series on the history of comic books and their links to cinema. In part 1 he talked about the early days and the original superheros. Part two looks at the formation of the Comics Code Authority which tried to censor and regulate comics in post-World War II America.

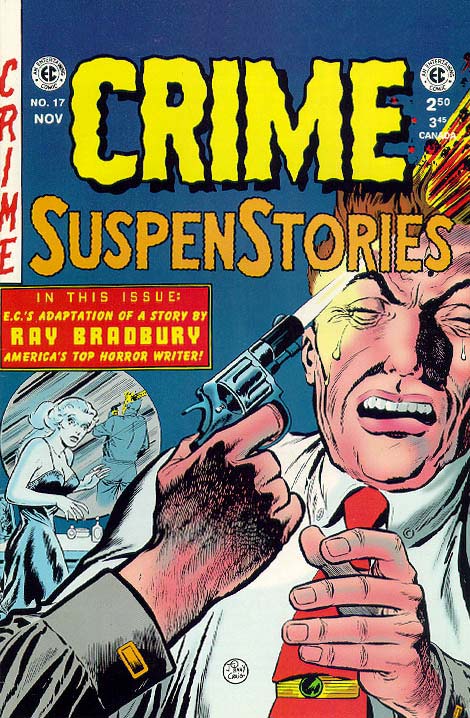

Assuaged of their fears that the world would end and that an insane and evil despot might yet conquer the earth with his legion armies, children of the late 1940s found that they didn’t really need superheroes as much as they’d used to. The superhero comic book was waning in popularity towards the 1950s with genre titles that featured stories of suspense and horror, or hustling gangsters, or hard-boiled detective yarns becoming more popular. Superheroes were forced to adapt or die as many superhero oriented titles folded. Many retreated back to the pages of single stories within anthology titles like Action or Detective Comics, where they had originated from. There was, however, a far greater force at work which would truly test the resilience of the superhero.

Assuaged of their fears that the world would end and that an insane and evil despot might yet conquer the earth with his legion armies, children of the late 1940s found that they didn’t really need superheroes as much as they’d used to. The superhero comic book was waning in popularity towards the 1950s with genre titles that featured stories of suspense and horror, or hustling gangsters, or hard-boiled detective yarns becoming more popular. Superheroes were forced to adapt or die as many superhero oriented titles folded. Many retreated back to the pages of single stories within anthology titles like Action or Detective Comics, where they had originated from. There was, however, a far greater force at work which would truly test the resilience of the superhero.

Much like the initial KA-BOOOM with which superhero comic books took flight in the 1940s, in the 1920s and 30s Hollywood cinema had featured its own golden age as genre film making flourished under what is now referred to as the Studio System. As if a prelude to the inevitable regulation of the comic book industry, Hollywood’s prolific streak had been somewhat culled years earlier as anxiety grew amongst a generation of parents and church officials concerning the immortal souls of their young and impressionable children.

To stamp out immorality in Hollywood and curtail depictions of sex, violence and most other enjoyable activities on film (sedition, smuggling, etc.), which could possibly seduce children and adolescents (as well as adults) to the “Dark Side”, the Motion Picture Production Code was created and it was to inform cinema throughout the 1930s and beyond. The production of comic books was regulated in much the same way as none of the anxieties surrounding young people and their impressionability had been quelled by the 1940s and 50s. These growing anxieties would actually be entirely realized in 1955 by James Dean in Rebel Without a Cause and the birth of a rebellious, teenage counterculture.

The furor over the inappropriate depiction of crime and sex in comic books was catalysed, if not partially caused, by a book entitled, in an appropriately dramatic fashion, Seduction of the Innocent: the Influence of Comic Books on Today’s Youths written by one Fredic Wertham. Wertham’s books set out to defame comic books of all varieties; superhero, horror, detective, even westerns, under the premise that images depicting violent and/or criminal behavior would influence children to act in a similar fashion. He also tried to show that sexually suggestive images were routinely hidden in comic books and most famously suggested that the basis for Batman and Robin’s relationship was a homosexual one.

Wertham eventually wound up testifying in front of the United States Senate Subcommittee on Juvenile Delinquency where he testified that comic books which depicted violence, as well as advertised items such as toy guns, were predisposing juveniles to delinquency. The entire transcript of Wertham’s testimony can be found here although be warned, it’s a bit of a read. The hearings of the Subcommittee were carried out over three days, on April 21st, 22nd, and June 4th 1954 (the transcripts of the hearings in their entirety can be found here, but again they do go on a bit). In the wake of these hearings, which were hugely damaging to the comic book industry, and fearing the implementation of government regulation, the Comics Code Authority was established to regulate and essentially censor comic books. All comics would have to be in line with what became known as the Comics Code in order to gain distribution from wholesalers. Not adhering to the code meant that your comic book wouldn’t have the little black and white “Approved by the Comics Code Authority” sticker on the cover and that distributors wouldn’t touch your book, effectively meaning that short of taking to the streets and hocking each issue yourself there would be no way to sell your title to the general public.

Wertham eventually wound up testifying in front of the United States Senate Subcommittee on Juvenile Delinquency where he testified that comic books which depicted violence, as well as advertised items such as toy guns, were predisposing juveniles to delinquency. The entire transcript of Wertham’s testimony can be found here although be warned, it’s a bit of a read. The hearings of the Subcommittee were carried out over three days, on April 21st, 22nd, and June 4th 1954 (the transcripts of the hearings in their entirety can be found here, but again they do go on a bit). In the wake of these hearings, which were hugely damaging to the comic book industry, and fearing the implementation of government regulation, the Comics Code Authority was established to regulate and essentially censor comic books. All comics would have to be in line with what became known as the Comics Code in order to gain distribution from wholesalers. Not adhering to the code meant that your comic book wouldn’t have the little black and white “Approved by the Comics Code Authority” sticker on the cover and that distributors wouldn’t touch your book, effectively meaning that short of taking to the streets and hocking each issue yourself there would be no way to sell your title to the general public.

What makes all of this so very galling is the code itself. It can at times be easy to look back at the mortifyingly prudish sensibilities of our predecessors and have a hearty laugh, but even by the most conservative contemporary standards the code was incredibly stringent, granting the censor an obscene amount of credence over artists, writers, and their content. The very first entry of the code sets the standard for just how bleak the restrictions were. It reads;

(1) Crimes shall never be presented in such a way as to create sympathy for the criminal, to promote distrust of the forces of law and justice, or to inspire others with a desire to imitate criminals.

This seems mind-numbingly repressive, especially given the ubiquity of the anti-hero in contemporary culture (think Walter White and Tony Soprano), but the code continues in rolling out restrictions which only grow in absurdity as they seek to tailor story elements with growing specificity.

(6) In every instance good shall triumph over evil and the criminal punished for his misdeeds

The majority of the code aims to curtail depictions of crime and violence (or gore) which effectively took the teeth out of all horror and crime titles under publication in 1954. This was due to the fact that the Senate Subcommittee on Juvenile Delinquency had found these genre titles to be the most potentially harmful to young readers. The code continues with an outright ban on kidnapping as well as a ban on showing clever means of concealing weapons. In a not so subtle move against the horror comic genre, and one which effectively shut it down, the first point of General Standards – Part B reads;

(1) No comic magazine shall use the word horror or terror in its title.

The code goes on to put an outright ban on all scenes pertaining to “or instruments associated with walking dead, torture, vampires and vampirism, ghouls, cannibalism, and werewolfism” and further states that “scenes of horror, excessive bloodshed, gory or gruesome crimes, depravity, lust, sadism, masochism shall not be permitted”. These restrictions forced most horror titles to become defunct, seeing as distributors would not be willing to ship the titles considering they were not endorsed by the Code.

While the Code put huge restrictions on the content of the entire medium, it also introduced some propositions which seem fair even today. Its final section outlines new regulations in terms of what is appropriate to advertise in comic books considering such advertisements would be targeting children and states that “Liquor and tobacco advertising is not acceptable.” The code also deals with a point which is still contentious today, namely the representation of women in comic book illustrations, setting the standard that “Females shall be drawn realistically without exaggeration of any physical qualities.” Anyone who has read any comic book over the past twenty years would be able to safely attest that this is a point which has been flagrantly ignored and that the depiction of women in the industry is one of its major failings.

While the Code put huge restrictions on the content of the entire medium, it also introduced some propositions which seem fair even today. Its final section outlines new regulations in terms of what is appropriate to advertise in comic books considering such advertisements would be targeting children and states that “Liquor and tobacco advertising is not acceptable.” The code also deals with a point which is still contentious today, namely the representation of women in comic book illustrations, setting the standard that “Females shall be drawn realistically without exaggeration of any physical qualities.” Anyone who has read any comic book over the past twenty years would be able to safely attest that this is a point which has been flagrantly ignored and that the depiction of women in the industry is one of its major failings.

Even against some protest, the Code (in its entirety here) stuck and it would remain in place for decades after its initial inception. It would take forty seven years for Marvel to forego the authorization of the Comics Code on all of its titles, with the publisher doing so in 2001, and it took DC another ten years before it made the move itself in 2011. It would be remiss of me to imply that the standards of the original 1954 Code were pristinely in place nearly fifty years after their conception.

Even though the Code would grow to be outdated, ignored, and eventually dropped by publishers, it had a massive effect on comic books and especially on the predominance of superheroes within the medium. Even though the popularity of the superhero had been waning after WWII, the Comics Code ensured that genre titles like crime and horror comics were essentially unpublishable and so the ever adaptable superheroes were able to step up and, realigning themselves as squeaky clean champions of Truth, Justice, and the American Way of Life, step back into the lime light and reaffirm themselves in the public consciousness. Clouded by the restrictions of the Comics Code creativity would inevitably strike and with a Flash of lightning the Silver Age of Comic Books would be born…

Check back for Part Three – Silver Age Marvels.