Jose “Pepe” Llulla, the Gravedigging Duellist

New Orleans has always been the least typical of American cities. The state’s French origins sets apart from the original British founding states, while its long heritage as the capital of its own colony state sets it apart from the states carved out of the frontier. Only Texas has a similar origin, joining the union as a fully fledged entity in its own right. Yet the French heritage is not the only strain of European culture running through the city – forty years before the Louisiana Purchase of 1803 it was ceded to Spain in the Treaty of Fontainebleu, and only reverted to French rule three years earlier. While the French influence remained the strongest, Spaniards too would call the city home even after it had become American. One such man was Jose Llulla, the last great fencing master of New Orleans.

New Orleans has always been the least typical of American cities. The state’s French origins sets apart from the original British founding states, while its long heritage as the capital of its own colony state sets it apart from the states carved out of the frontier. Only Texas has a similar origin, joining the union as a fully fledged entity in its own right. Yet the French heritage is not the only strain of European culture running through the city – forty years before the Louisiana Purchase of 1803 it was ceded to Spain in the Treaty of Fontainebleu, and only reverted to French rule three years earlier. While the French influence remained the strongest, Spaniards too would call the city home even after it had become American. One such man was Jose Llulla, the last great fencing master of New Orleans.

Jose Llulla, known always as “Pepe”, [1] was born in 1815 in the port town of Mahon on the Mediterranean island of Minorca. Nowadays Minorca is a Spanish possession, but at the time it was a former independent Spanish kingdom which had been conquered by the British and Dutch in 1708, and was now a British possession. Perhaps it was growing up under the rule of foreigners like this which awakened such fierce nationalism in the young Pepe. He left Minorca as a cabin boy at a young age and worked his way across the Atlantic, becoming a regular on the route between Havana and Louisiana. Eventually he had enough of sailing and settled in Louisiana. He had a reputation as a tough and crafty fighter even then, and became a bouncer in one of the more colorful bars on the waterfront. Such men had to be skilled in a variety of weapons, from knuckle dusters to knives. Pepe’s life, however, was to be changed forever when he decided to expand his repertoire to include swords.

At the time New Orleans was a noted hotbed of duelling, and the slightest stain on a gentleman’s honour was likely to lead to an invitation to “the Oaks”. Men fought and killed each other over matters as trivial as the placement of a chair at dinner. [2] In this environment, skill with a sword could thus mean the difference between life and death, and so unsurprisingly schools teaching swordsmanship were popular. Young Pepe enrolled at the Salle d’Armes of one Monsieur L’Alouette, who had come to Louisiana from Alsace. L’Alouette soon realised that Pepe was a cut above his usual students, and hired him to come work at the Salle. In time the student became a protege and the protege became a trusted friend and heir, so that when L’Aloutte died the Salle d’Armes L’Aloutte became the Salle d’Armes Llulla, and the cabin boy from Minorca became one of the premier duelling masters of New Orleans.

There are numerous stories of Pepe’s exploits as a duellist. One of the earliest came while his master, L’Alouette, was still alive. The Frenchman was intrigued by the new American innovation in weaponry, the bowie knife, and asked Pepe to fight him with wooden replicas in an exhibition match. He had underestimated his student’s skill however, and soon found himself losing badly while having failed to score a single touch on Pepe. Annoyed, he made a reckless attack on the Spaniard, who parried it with such force that he broke two of his teacher’s ribs. Naturally this terminated the duel, though luckily for Pepe L’Alouette was not a sore loser. Pepe’s expertise with weapons extended further – he was an outstanding shot with a pistol, capable of shooting silver dollars from between fingers, and of shooting an egg off his son’s head. He even once accepted a challenge to duel with machetes, and issued one to duel with shotguns, though in both cases the other party decided to apologise before the duel.

This was a common occurrence as his fame spread, though he still fought (and won) 20 or 30 formal duels as well as acting as a second for at least three times that many. On one such occasion the opponent’s second, a German fencing master of no small renown, stepped in for his principal. Pepe knew that his own principal was not match for the German and so stepped in as well, disposing of the foreign master in two cuts that left him bleeding on the ground. One other tale has him, before a fight, telling his second (correctly) exactly which coat button he would stab the man through. Despite all this, his skill was so great that he only ever actually killed two of his opponents in duels. Most of his fights ended with the edge of his blade lightly pressed against the opponent’s neck, at which point they would generally see things his way.

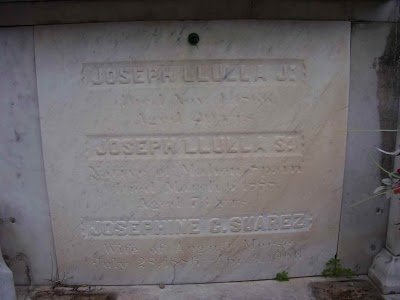

Though Pepe’s skill was undeniable, he lacked the patience for sustained teaching and generally left the day to day running of the Salle d’Armes to trusted assistants. He was married, and had at least two children – a son named Jose, who died in 1863, and a daughter named Josephine. His brother also came from Minorca to live in New Orleans. Instead he spent a portion of his time on various business ventures, including a slaughterhouse and a sawmill. His most successful and noteworthy endeavours however were in the purchase of land – two pieces of land in particular, One was Grande Terre Island in Barataria Bay, which had the base of the notorious pirate Jean Lafitte, in his free town of Barataria. When Lafitte and the Baratarians had agreed to fight on the American side in the war of 1812, the Americans had built a fort on the island to prevent the bay falling back into pirate hands. Llulla purchased the rest of the island and raised livestock there, doing well despite the occasional storm.

Pepe’s most famous purchase however was of the St Vincent de Paul Cemetery on Louisa Street, along with two adjoining blocks which he used to expand it. The humour in a famous duellist having his own graveyard was not lost on the people of New Orleans, and a joke soon spread that Pepe had a special section in the cemetery reserved for his victims. The New Orleans tradition was for large above ground family tombs (due to the damp ground), and space in the new cemetery sections sold well to newer families.

Pepe became a wealthy man from the graves, though he still faced prejudice for his lower class upbringing. On one occasion the city held a tournament for masters of the broadsword. Pepe was refused entry as he was told he did not have the necessary European qualifications. He challenged the Frenchman who excluded him to a duel with the broadsword, and after cutting him open a few times issued his profound apologies for doing so without the correct piece of paper to back it up.

While snobbery was one cause of Pepe’s duels, another was his support for the Union in a Rebel state during the Civil War. The most common cause, though, was his strong sense of Spanish nationalism. At the time New Orleans was a refuge for Cuban revolutionaries plotting to return and throw off the yoke of Spanish rule, and naturally they and Pepe clashed on multiple occasions. In 1853 when anti-Spanish rioting gripped the city, Pepe escorted the Spanish consul from the city to protect him from the mob, and then challenged any Cuban who dared to come and face him in a duel. None dared accept, though several attempted to attack him in less honourable ways. At one point seven drunken sailors attacked him in a bar he owned. Pepe (who never drank) knocked five of them down with an iron cudgel he kept behind the bar, and the other two fled. On another occasion in 1869, two men attempted to assassinate him outside his office at the cemetery. The attempt which ended with them fleeing through the tombs while Pepe fired over their heads. He later explained that he did not wish to get a bad reputation by gunning down a man who was running away. Eventually the Cubans found someone prepared to duel Pepe, an Austrian officer named Meyer. The duel was with pistols at thirty paces, with them to advance and fire at will on the signal. (Thirty paces was outside effective pistol range for most people, hence the advancing.) When the signal was given the Austrian advanced forward, but saw that Pepe was standing half turned away, apparently ignoring him. When the Austrian began to raise his pistol then Pepe whirled and fired, straight into the man’s chest, making him (according to Pepe) the second person he had ever killed.

Pepe’s strident defence of Spanish honour was not without reward, as the Spanish government made him a Knight of the Order of Charles III in recognition of his service. More treasured by Pepe himself however was a portrait that was sent to him from Havana by local Spanish loyalists grateful for his support, which was decorated with hair donated by the ladies of the city to show their appreciation. In later life he spent most of his time out on Grande Terre, preferring the quiet of the countryside, but in March 1883 he came into New Orleans, probably to visit his daughter, who had married a man named Victor Suarez and taken over the running of the cemeteries. While there he fell and died at the age of 73. He was buried in his own cemetery, alongside his son. So passed the last of the great American duellists.

Images via Crescent City Eskrima, Old New Orleans, and Paige Pixel.

[1] A common nickname for men named “Jose” in Spain, due to the name’s origin as a diminutive form of Joseph.

[2] Not an exaggeration. When Monsieur de Lauzon set his sister’s chair slightly too close to that of Monsieur Morel’s young lady friend, the latter challenged him to a duel and killed him under the Oaks two days later.