Pop Culture & the Myth of the Misogynist

You’ll have to excuse the article title if it’s misleading. I’m not trying to argue that misogyny only exists in the crazed imaginations of militant, man-hating, feminists; the kind of feminist that only exist in Milo Yiannopoulos’ mind. Instead I’m going to look at how popular culture has skewed our perspective of what a misogynist should look like.

Popular media in all its forms has a tendency to crystallise depictions of groups or traits into a one size fits all model. Any kind of depiction positive or negative, true or untrue seeps into our collective conscious. Lazy characterisation or crude caricature, when reproduced over and over, begins to obscure its clumsy origin.

Since the dawn of American cinema, African American men were largely depicted as hyper-sexualised deviants who wanted to celebrate their relatively new found freedom by rapin’ them some white women. D.W Griffiths’ polarising Birth of a Nation has a famous scene where a character – in blackface – chases a woman through a forest like a deranged minstrel.

The implication is clear.

From 1915 onward this caricature of the hyper-sexualised black man with an unquenchable appetite for the wives, girlfriends, and daughters of his former oppressors became so pervasive in its constant iterations that it largely stopped being seen as a caricature.

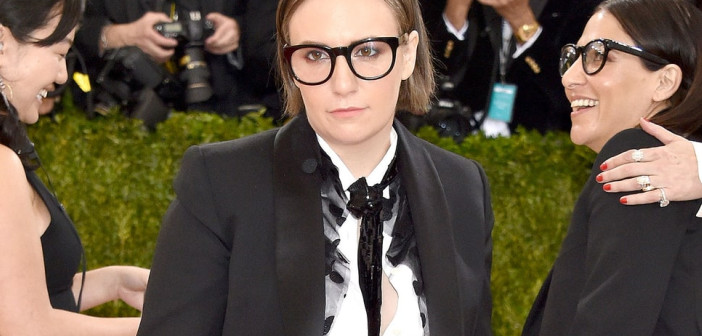

So much so that by 2016, a whole 101 years since Birth of a Nation was released, Girls star Lena Dunham seemed damn right offended that Odell Beckham Jr., a black man, didn’t immediately want to chase her, a white woman, through a forest.

These damaging depictions, endlessly repeated like Facebook Minion memes, can get so entrenched in the collective mind it’s easy to forget that they are caricatures. The hyper-sexualised, monstrously endowed black man became a recognisable trope, rather than a fabricated manifestation of the former slavers’ fear.

This unfair representation of black men continues but at the very least it’s a conversation that’s happening. In spite of Warren Beatty attempting Eric Cartman’s White Person Method to spirit away Moonlight’s best picture win, that film proves that more nuanced, more complex characterizations of individuals within minority cultures are beginning to be explored in mainstream pop culture.

More insidious than the obvious negative portrayals of groups and minorities is the ham-fisted depiction of characters like misogynists and rapists.

On TV and film, the man who disrespects women is almost ubiquitous in his depiction as the hyper-masculine “jock” character; the posturing athlete, always in a sport jacket, surrounded by his identically dressed hive mind cronies. Even TV shows that take a stab at analysing slut shaming and rape culture like Netflix’s 13 Reasons Why, falls back on the trope of the jocks being the cruel exploiters, and the shy indie music fan being the respectful hero.

Closer to home, Louise O’Neill’s harrowing novel, the unflinching Asking For It, frames the local GAA athletes as the book’s predators.

There is absolute precedent for this, of course. There are hundreds of examples where athletes seem to get preferential treatment in the sexual assault cases they’re accused of; Brock Turner being the obvious example. In the media, Turner was described as a college swimmer about as many times as he was described as a perpetrator of sexual assault.

So the athletic, uber-male is the misogynist rapist in real life and so he’s depicted as such on TV screens, bookshelves, and cinemas. That would be fine of course if that depiction wasn’t so one-dimensional.

I’m not suggesting that media portrayals are so powerful that they completely warp our perceptions. That’s like suggesting that violent video games turn people into murderers or make them act more violently (that’s ridiculous, all the bodies I buried in my back garden where there long before I ever played GTA V). But constant one-note media portrayals can reinforce assumptions and strengthen stereotypes. If that sounds like a stretch, ask a Muslim going through airport security what they think.

The myth of the misogynist is not unlike the rapist monster myth that was articulated with guile and precision by Tom Meagher. When seeing his wife’s rapist and murderer in court, Meagher realised that the man wasn’t some inhuman crab person but an ordinary looking human being with thoughts and opinions. Meagher points out the disparity in how we imagine rapists to be – golems in back alleys – to how rapists really are, oftentimes friends, acquaintances, and boyfriends of their victims.

A false unchallenged stereotype of a character or character trait, even a deplorable character trait isn’t just lazy writing – it’s damn right misleading.

The high church of geek culture, comic book conventions, have been at the forefront of this disparity between reality and media depiction for some time. It’s why social movements like Cosplay is Not Consent are very necessary to combat a real problem of inappropriate groping and nastiness seeping into conventions.

The usual, mini skirt rational is often part of the vitriol of defending this groping: ‘cos if a woman is dressed in the tight leather of a superhero outfit, or the revealing costume of a video game character, then she’s asking for it.

An example of this mono mindset was played out recently when Emma Watson was called a hypocrite for taking part in a glossy photo shoot while having the audacity to call herself a feminist. It’s almost like Watson forgot that feminists only ever wear doc martens, plaid shirts, and necklaces made from the scrotums of enemies of the matriarchal revolution.

The problem at conventions is by no means confined to Trumpland, as we unfortunately learned these past few weeks. A young woman, displaying amazing courage, waived her right to anonymity and named the man who attacked and raped her. The attack in question happened at the 2015 ArcadeCon in Dublin.

How often in the media is the skinny comic book fan depicted as the seething woman hater? What about the The Lord of the Rings fanatic, how often is he seen grabbing ass and high-fiving his fellow Frodos? Rape isn’t just committed by those seen as overtly masculine, or by those whose roaring testosterone when not channelled on the GAA pitch is channelled directly to the dick.

Rape doesn’t happen because the sexual urges of an ubermensch overcomes all reason. Rape is about power, about hatred, and the ugly expression of that hatred.

If we ever want to get a bit closer to understanding that hatred, and why it’s so often directed at women, it’s important that our stories – our reflections and expressions of reality – represent misogyny in all its dark dimensions.