Baudrillard, Simulcra and Her | Alienation in the Modern Digital World

In the David Fincher movie The Social Network (2010), a main character announces at a party; ‘We used to live in towns and cities. Now we will live on the internet.’ These words, though spoken during a coke-fuelled shindig and created from the pen of renowned exegetist Aaron Sorkin, are prescient of the reality we now inhabit. We are all participants of a virtual reality. Facebook is used to publicise both the individual and the brand. In just ten years, it has gained over one billion users. Twitter gives a soapbox to the individual and thus a direct line of communication to millions of people. Tumblr is a social media network/art portfolio for people who are too pretentious for Facebook. Careers in media and art have been made out of this. Even as I write this, I am sitting inside a huge library, surrounded by easily over a hundred people. Some are working, some are pretending to. What is definite is that everyone has either a smartphone out or a social network tab open. We are all communicating, just not to each other. We are using some form of online persona to communicate. Persona is a substitute for a person in the digital age. We are using hyperreal signs as our representation.

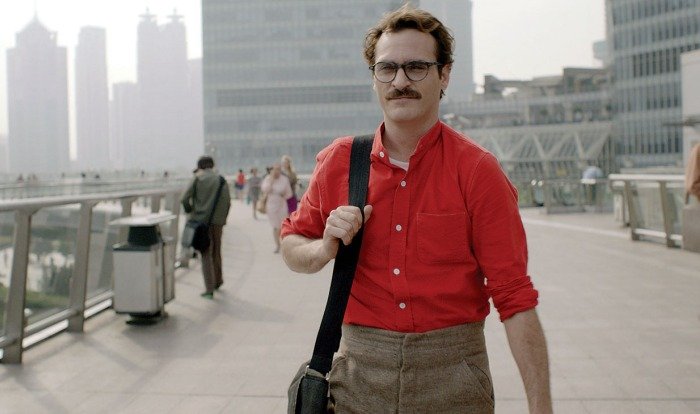

Though social networks are programmed to seem as personable as possible, something is lost in execution. Walter Benjamin wrote that the loss of the aura in art was a symptom of a larger problem in culture. The audience communicates with art in a more submissive way; ‘…the individual no longer contemplates the film per se; the film contemplates them.’ This break in communication has led to a sense of cultural malaise. How can we feel attached to something that exists as a concept, rather than a fully fleshed entity? This question of technological dread is asked in the recent movie Her. The film, written and directed by Spike Jonze, follows the story of Theodore Twombley, as he navigates his new relationship; a romantic relationship with an Operating System called Samantha. Theodore lives in a world meant to look like what the very near future is; glass buildings, soft pastel shades and interpersonal technology. In the swarming cityscapes, people walk around talking; to their devices. The image of adults openly talking aloud to a machine in public should look ridiculous to a contemporary audience. But it doesn’t; it just resembles any other modern city, albeit with better dressed people. The total anonymity of the city plays into the idea of the Simulacrum. The architecture is tasteful and anaemic; there is nothing of historical value or artefact to be seen; the citizens amble around wearing the same colour palette. Jean Baudrillard states the simulacrum is the stage of simulation; a hyperreality. The city of Her is reminiscent of Borges tale described in Baudrillard’s The Precession of Simulacra;

‘the map precedes the territory… it is the map that engenders the territory and if we were to revive the fable today, it would be the territory whose shreds are slowly rotting across the map. It is the real, and not the map, whose vestiges subsist here and there, in the deserts which are no longer those of the Empire, but our own.’

What is applicable of this idea in the film is the uniformity of the citizens of near future Los Angeles. Everyone subscribes to their role in society accordingly. In another film, this could be a model of Orwellian hell; here it is embraced and encouraged by the people. There is no all-encompassing regime that is forcing this hegemony; the people are all willing participants. The city is representing an image of near future Los Angeles. The location where much of the city is filmed is actually Shanghai, China; a city that actually is a part of a authoritarian regime. The director described the appeal of filming there thusly; ‘we ended up going to Shanghai and using very specific, curated areas of Shanghai… it was this idea that we were trying to make this very warm, tactile world, with the materials and fabrics and the woods, and create this world that felt like this utopic world that everything’s nice.’ What feels unnerving about the cityscape is that it is a vision of unreal perfection. It is full of unreal spaces, much like Samantha the OS.

The relationship between Theodore and Samantha has no physicality in the traditional sense. Through their conversations, they sound like lovers separated by geographical distance, rather than physical. Their love is summarised tenderly in the song they create together; the Moon Song. The lyrics speak of isolation but with the promise of loving companionship; ‘your shadow follows me all day/ Making sure that I’m okay and/ we’re a million miles away.’ The image of them being at an impossible distance away from Earth seems like an apt metaphor about their feelings for one another.

[arve url=”https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CxahbnUCZxY”]

With Samantha, Theodore has all the comfort and support of a relationship but none of the usual trouble. Samantha will never complain about menstrual cramps, she will never moan about how ‘fat’ she feels, and Theodore will never see her looking worse for wear. Though that sounds like a tired stereotype of women, it is part of what Theodore fears in his relations with women; their human fallibility. What he gets from the Samantha is the ‘authentic’ emotional connection. The two argue, of course; she wants to try out a new sex position, he accuses her of being nosy. Though these arguments are a simulation of a lover’s tiff, they are not rooted in reality. Their relationship problems run contrary to the very reality of their relationship. Samantha want to use a body double to make love to Theodore, but the experience horrifies him. At this point, Theodore, an able-bodied man, unwillingly confronts the unreal space that is Samantha’s existence. She represents all the ideals that Theodore has been looking in a woman, in a life partner. She is a hyperreal space however. By taking on the role of lover, there is a discombobulating of her actual duties. Theodore chastises her for reading his emails, though her operational function is to organize his computer and life. After all, she is computer software. This fits in to Baudrillard’s definition of hyperreality itself; ‘Hyperreality involves the fragmentation of meaning, and of language, so that an object refers not necessarily to another object but to a representation of an object.’

Her has been described as a movie to be watched by ‘internet addicts’. With everything we do being open online, the film could better be described as a film of the moment. Not the buzzword ‘moment’, but this moment in time of where people are psychologically in the world and how we react and interact with each other. Currently, ‘other’ is becoming a series of stimuli. Disguises of truth are worth more than truth itself.

Baudrillard stated that signs have taken precedence over the things signified. What is real has become lesser in importance and worth, than what is represented. In Her, Theodore is paid by people to write ‘personalized’ letters for their loved ones. This letters, created on a computer screen, have the appearance of a handwritten note, the words in stunning calligraphy, in order to look as romantic and authentic as possible. The company is literally named BeautifulHandwrittenLetters.com. The letter writers use a person’s physical idiosyncrasies and personal history to create these letters. Meanwhile, the recipient is led to believe that their letter has come from their significant other. The business is highly lucrative and successful. It is successful through being a well thought out brand disguised as intimacy.

It becomes ever clearer to the audience that the whole enterprise is a simulacrum in of itself. It promises its users an authentic portrayal of love, but it is lying to the people who will actually receive these letters, by proclaiming the author to be anyone but a moustachioed sad sack behind a computer. No one ever seems to ponder; ‘How can someone love someone when they pay other people to tell them that?’ What disturbs the viewer about this is how natural people are at accepting both the existence of such a business and its product. Though really, what is the difference about BeautifulHandwrittenLetters.com and a standard Hallmark card? Both businesses use sickly sweet sentiment to sell their wares. The ethics of a Hallmark card are not argued about to huge extent in the contemporary world. The acceptance of the simulated idea of love conveys how relevant Baudrillard’s work is to the 21st Century. This acceptance is in stark contrast to rampaging Iconoclasts as described by Baudrillard in The Divine Irreference of Images;

‘One can live with the idea of a distorted truth. But their metaphysical despair came from the idea that the images concealed nothing at all, and that in fact they were…perfect simulacra forever radiant with their own fascination.’

The selling point of the Operating System is that it has humanising features. It is able to talk back to the user and carries out conversations about any topic imaginable. It has knowledge and information about anything the user would want to know about. It is basically, an organiser/encyclopaedia equipped with an affable voice and the caring of a friend. Theodore enters into his own simulacrum and leaves behind his pained history of divorce and rejection. His decision to go into a new relationship with Samantha is a way to heal himself from loneliness.

‘We leave history to enter simulation. […] This is by no means a despairing hypothesis, unless we regard simulation as a higher form of alienation – which I certainly do not. It is precisely in history that we are alienated, and if we leave history we also leave alienation.’

Featured Image Credit