Mary Frith aka Moll Cutpurse, the Roaring Girl

Mary Frith was born sometime in the 1580s – 1584 is a reasonable guess, and is given as a fact by some sources. She came from a relatively respectable background – her father was a shoemaker, and she had an uncle who was a churchman of some sort. That’s about as detailed as a lot of the facts on Mary get, though we do have the records of her interaction with the law to rely on. The first of these came in 1600, when Mary was arraigned for the theft of two shillings. A hundred and fifty years later that sum would have been enough to qualify as “grand larceny” and to see her hanged, but luckily for Mary the law at the time was less bloodthirsty, and her uncle was able to get her released.

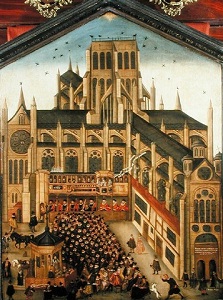

Mary’s family decided, in order to give her a fresh start, that they would ship her off to the American colonies where young women were much in demand and she would have no trouble finding a husband and settling down. Mary was less than keen on this idea though, and she jumped overboard while the ship was in harbour. Once she swam to the shore she resolved to make her own way in the world. This she did through crime, joining a gang of pickpockets who preyed on people in the area of St Paul’s Cathedral. Mary was a “Whipster”, one of the skilled pickpockets who actually did the “Feat” while the mark was distracted by the “Bulk” and who then handed the goods off to a “Rub”. Mary proved to be a skilled Whipster, and soon earned the nickname of “Moll Cutpurse” – a cutpurse being a pickpocket, while “Moll” was both short for Mary and a word used to describe a rough and tumble woman. And that was exactly what Moll Cutpurse was.

Moll was a skillful pickpocket – not skillful enough to avoid being caught though. She earned a few stints in jail and was allegedly “burned on the hand” four times. This seems odd, as branding in this way was usually meant to ensure that a defendant could not plead “benefit of the clergy” (receiving clemency from a death sentence by reciting a bible passage) more than once. However it might be that Moll’s gender gave her repeated clemency, or that the rules were more laxly applied in those days. Moll acquired a certain celebrity at this time for her habit of wearing male apparel, and for smoking a man’s pipe – the former technically a crime, though not one often prosecuted as long as people weren’t too public about it. Moll herself was often described in less than flattering terms, and she did have a reputation for being a lot less sexually active than people expected of the criminal classes at the time – though whether this was due to preference or to her appearance is impossible to say.

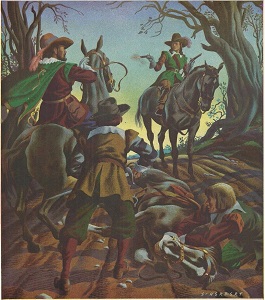

Moll became well known for her male attire, in defiance of the laws forbidding such, and on one occasion she was offered a bet by William Banks that she would ride across London dressed as a man on his famous horse Marocco. Marocco was a performing horse, who Bankes had trained to perform a huge number of tricks on command – walking on two or three legs, urinating on command, counting items, and more. In addition to his animal training abilities Banks was a master showman and publicist, and so this type of stunt was right up his alley. At first the went well until one of Moll’s enemies spotted her and called the crowd against her. The whole thing ended with her galloping away in an undignified manner. She did win the bet though, and Banks got his publicity boost. He wound up taking Marocco on a European tour that saw Banks twice nearly being burned as a witch, before he returned to England and got a succession of high-paying jobs training horses for aristocrats that set him up comfortably for life. He may have been one of those high-placed friends who used their influence to see to it that Moll was usually treated leniently by the courts.

It was in 1610 that Moll officially became a celebrity. She was a character in The Madde Pranckes of Mery Mall of the Bankside, by the playwright John Day. Day was not unfamiliar with criminal types – he was described by contemporaries as a “rogue”, and may even have been arrested for murder the year before. Sadly this isn’t one of the few plays of his that survive. We do still have the second play Moll appeared in though, which came out the following year. This was The Roaring Girl, by Thomas Middleton and Thomas Dekker. In it a young man, aware that his beloved Mary won’t be accepted by his father, tricks him into thinking that he plans to elope with Moll Cutpurse. Moll (a rogue with a heart of gold) plays along and the horrified old man is eventually relieved enough to discover he had been tricked that he gives his blessing to the real young couple. Moll herself gleefully declares that she would never marry.

The plays generated enough interest that Moll got a show at the Fortune Playhouse, a notoriously rowdy theatre. She wore men’s clothing and told stories, played the lute and argued with the audience. [1] It may have been the very first time a woman appeared on stage in an English theatre. The story is that this public appearance was what finally saw Moll brought up on charges for her cross-dressing. She was condemned to do public penance, standing in a white sheet at St Paul’s Cross on a Sunday while a sermon inspired by her crimes was given to the crowd. Apparently she put on a great show of penitence, though this emotional display was aided by being extremely drunk on “sack” – sweet fortified white wine. In 1614 Moll proved The Roaring Girl wrong by getting married. Her husband’s name was Lewknor Markham, and he was the son of a playwright named Gervase Markham. (Gervase was a friend of William Banks, the horse trainer who made a bet with Moll years earlier.) It’s uncertain how serious the relationship was – he seems to disappear from her life afterwards, though it’s possible he just died of an infection or in a brawl or one of the many other ways to die in 17th century London.

Whether with money from her entertainment business or from her marriage, Moll set herself up officially as a “pawnbroker”, and unofficially as a fence. Her celebrity proved to be an asset, as people who knew her reputation would often approach her and ask her to “retrieve” goods that had been stolen from them, with no questions asked. Usually this was watches and jewelry that had sentimental value beyond the monetary, and as long as they were will to pay then Moll could usually find the person who had it and buy it back. On one such occasion (as Moll later told the tale) the gentleman looking for his watch turned out to be a police plant, and as soon as she returned it she was arrested for handling stolen goods. Moll was arraigned for trial, but one of her fellow pickpockets saved her from jail by stealing the watch (the key evidence) from the police officer who was bringing it up through the court. As a result Moll was acquitted.

On another occasion Moll was engaged by a young gentleman named Henry Killingrew, who had been robbed following a business engagement with a prostitute the night before. He had been busy doing up his trousers while she helped herself to the contents of his pockets, which included his watch and a gold seal ring. From a chance remark made by the prostitute Moll was able to identify her as Mary Dell, and the pair confronted her in her house before having her arrested. However Mary was married, and her husband in turn laid a complaint against them and accused them of barging into his house and threatening the pair with no evidence. The verdict in the competing cases is not recorded.

Moll’s most scandalous enterprise was a dating agency, of a sort. She acted as a panderer and helped rich men find women willing to be mistresses, but that really didn’t surprise anyone. It was her reversal of this, where she would put young gallants in touch with older women seeking some excitement that really got people in a tizzy. Moll described the men she provided as “the sprucest fellows the town afforded”, and was amused to see some of them later presenting themselves in high society. Best of all, from Moll’s point of view, was that she got paid twice – once by the women, and once by the men. She also acted as a go-between and cutout for people engaging in more perilous affairs, something which gave her friends in high places who repaid her discretion with later leniency.

In actuality Moll seems to have spent most of the civil war as an inmate of Bethlehem Royal Hospital (better known as Bedlam). It’s likely that a notorious bohemian like her was an early target of the Puritan authorities, and some accounts have her paying a massive £2000 bribe to escape from the gallows and put herself into Bedlam instead. She was released in 1644, and proceeded to lay low for the next decade and a half. Moll developed “dropsy” in her old age – fluid retention in her tissues, usually painful and crippling. It’s a symptom rather than a disease, but as with many historical sufferers we don’t know why she got it. Still she did live until the ripe old age of 74, and died in 1659 at home in her bed unlike many of her criminal compatriots. Her will famously was supposed to make a request for her to be buried on her face with her “breech upwards”, in order that she might be as outrageous in death as she had been in life. Sadly that’s apocraphyal, but it does make for a good story.

The year after Moll’s death Charles II was restored to the throne of England, and in the following years something peculiar happened. Moll Cutpurse, terror of the streets of London, gradually made the transition from public menace to fondly remembered folk hero. Three sympathetic biographies were published after her death, all casting her as part of the “popular resistance” to Parliamentary rule. Perhaps this was simply a necessary part of rewriting history for the new regime, in order to convince people that in their hearts they’d been on the winning side all along. Or perhaps it was that the preposterous Moll Cutpurse represented all that people had missed from the pre-war period – the romance, the adventure and above all the fun she’d had.

Images via wikimedia except where stated.

[1] Essentially an early form of much modern standup comedy. The 1611 date is the most likely date for this to have happened, though some records indicate it could have been as early as 1605.

[2] The idea being that Dunlop tyres enabled safe travel and thus no more highwaymen. Apparently.