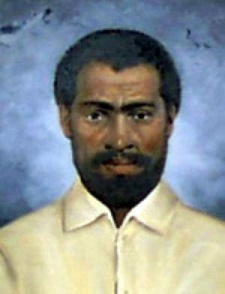

Nat Turner, the Bloody American Spartacus

Nat Turner was born into chains on the 2nd October 1800. His name was chosen for him by the man who owned him, owned him even before he was born. Nat’s parents were both slaves, and so he was a slave as well – that was the law in Virginia at the time. His grandmother, a woman given the name Bridget, had been captured in Africa at the age of thirteen by a rival tribe and sold to slave traders on the coast. At the time the European powers (mostly Britain, Portugal and France) operated what was known as the “triangle trade”. A ship would leave from Liverpool, for example, with a cargo of copper tools, cheap guns, decorative beads and so forth. These would be brought down to the west coast of Africa, where they would be traded with local leaders for slaves (usually enemies captured in raids or in war). The slaves would be shackled below decks, and the ships would set off for America. The ship that took Bridget went to Virginia, where the tobacco plantations depended on slave labour for profitability. There the slaves were sold, and part of the money from their sale spent on a cargo of tobacco and hemp. (Not a lot, as the slave ships were inefficient cargo transporters, but enough to boost the profits of the vessel.) The ships then sailed back to England, sold the tobacco and hemp and were ready to begin again. Bridget was bought by the Turner family, and so her son, and then her grandson Nat, were given the name of the family that owned them.

Bridget was an Akan, from the Gold Coast of Africa (modern day Ghana). The Akans were given the name “Coromantee” by their European owners, after the Africa trading port of Koromantse where most of them were bought. This was a classification more by a shared language than by any ethnic grouping. A large number of the Akans sold to the slavers were warriors captured in battle, and the ability of them to communicate with their fellow Akans led to them gaining a reputation as organisers of slave revolts. So notorious did they become for this that in 1765 a bill was proposed to ban their importation in to British colonies. The bill failed to pass, so colonists instead started forcing marriages among their slave across ethnic divides, marrying Akan men to Igbo women in an attempt to “dilute” the rebellious nature of the Akans. This was the stock of the woman who Nat Turner would later cite as his greatest influence growing up, and this was the stock of Nat Turner himself.

Nat’s mother was given the name of Nancy by the Turners, but we don’t know much about his father, Bridget’s son. Some sources claim that he escaped from the Turners when Nat was a small child. Nancy (like Bridget) had been brought over from Africa, though we know less about her origin. Nat was an intelligent child, who quickly learnt to read and showed a strong religious streak. In his own words (reported later at second hand), he was told that he was too intelligent, and he “would never be of any service to any one as a slave”. Instead, both his mother and grandmother assured him that he was meant for something better, and he believed them. As a teenager he became a preacher, reading from the Bible to other slaves at semi-clandestine religious meetings. At the age of 21 he ran away, but after a month he simply returned to the Turner plantation. In the woods he had received a vision, which he interpreted as a command from God to return to his “earthly master”. At the age of 22 he was married to a woman called Cherry, but that same year Samuel Turner, his then owner, died. The Turner estate was broken up, and the slaves he had owned were sold off separately. Nat was sold to a man named Thomas Moore and would never see his mother or his new wife again.

In 1825 while working in the fields, Nat had a vision. He saw “white spirits and black spirits engaged in battle, and the sun was darkened — the thunder rolled in the Heavens, and blood flowed in streams.” Inspired by this, he began preaching in a local church. Most people scoffed at the black preacher, but at least one white man (a repentant alcoholic named Etheldred Brantley) was baptised by him. Three years later Nat was in the fields once more, when he heard a loud noise and “the Spirit instantly appeared to me and said the Serpent was loosened, and Christ had laid down the yoke he had borne for the sins of men, and that I should take it on and fight against the Serpent, for the time was fast approaching when the first should be last and the last should be first”. All of these he took as signs that he was destined to lead a great rebellion to free his fellow slaves.

In 1830 Thomas Moore died. Nat’s legal owner was Moore’s young son Putnam, but when Moore’s widow remarried to John Travis then Nat was sent to work on her new husband’s lands. Nat had four trusted friends among the slaves on the Travis estate, named Nelson, Sam, Henry, and Hark. When an eclipse of the sun occurred in February 1831, Nat saw it as a black man’s hand, reaching out to cover the sun. This he took as a sign that his time had come at last. He and his friends began gathering recruits among the other slaves, with Nat’s preaching providing a cover for their meetings (though his own apocalyptic brand of religion was at the core of the rebellion). The date was originally set for the fourth of July, when the slaveowners would be distracted by celebrations, but Nat fell ill and the uprising was postponed indefinitely. A second eclipse in August jumpstarted it back into life, however, and a week later, in the early hours of August 22nd, the rebellion began.

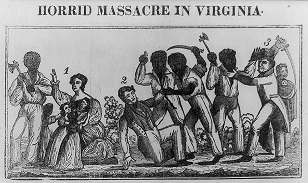

While many nowadays would sympathise with the rebellion of slaves, the actions they’re documented as having taken are much less sympathetic. Beginning with the Travis family, they traveled from plantation to plantation killing every member (including women and even small children) of every slave owning family they encountered. Non slave owners were not safe from their wrath either, though some poor white families were spared as it was felt that they lived no better than the slaves. Quite how much of this violence was at Nat’s bidding, and how much was just pent up aggression breaking forth, it’s impossible for us to say. Tradition often has it that he tried to reign in their excesses, but there’s little to back this up.

By noon on the 22nd, the rebels had attacked fifteen houses and killed around sixty people. In those houses there was only one survivor, a child who was hidden in a fireplace. Nat planned to march on the nearby town of Jerusalem with his force (now grown to around seventy men), to secure and fortify it. From there he could have led his people out into the swamps to found a separate colony [1] or, as he later claimed was his intent, continue rallying slaves into general revolt and bring the entire state to arms. However the local militia attacked Nat’s column, with a small force first finding and engaging them, and then the entire local militia reinforcing them. Not only was Nat’s force outnumbered but several of his men turned out to be too drunk to fight, having looted liquor from the houses they had attacked. Between casualties and those who fled, Nat’s force was reduced to around twenty men. Hoping for reinforcements they rode to a plantation owned by a Dr Simon Blunt, who had around sixty slaves they planned to recruit. The slaves, however, recognising that the cause was lost, instead attacked Nat’s rebels with clubs and tools. They broke and dispersed. The revolt was finished.

Over the next few days army units began to pour into Virginia to restore order to the state. The captured rebels were tried, with some being executed and others being sold out of state. Vigilante mobs of local militia roamed around killing any black man they encountered, whether he was free or slave. The violence spread beyond Virginia, as the latent paranoia that any slave-owning society must bear was triggered. In North Carolina, one militia company was reported to have killed forty black people in one day, looting $23 and a gold watch from them. This was condemned by another militia leader, not for the loss of life but for the theft of property that he felt belonged to the owners of those slaves. All told around two hundred slaves and free black people were killed – four times as many as the rebels had killed, and three times as many as had actually rebelled.

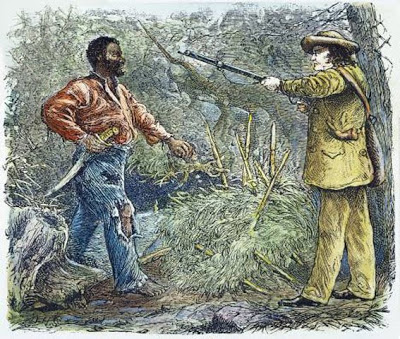

Nat Turner escaped capture for nearly two months, despite a large reward being offered for his capture. This was less to motivate those hunting for him, and more to guarantee that he would be brought in alive for trial. A local farmer eventually found him hiding in the woods less than two miles from where the rebellion had begun. He was immediately transported to Jerusalem and tried only a few days later. During this time a local lawyer named Thomas Ruffin Gray visited him and spoke to him. Gray would later write a book about Nat Turner, and it is from this (admittedly somewhat dubious) source that the majority of our insight into Nat’s intentions come. On November the 5th he was tried for “conspiring to rebel and make insurrection”, and pleaded innocent by claiming that his rebellion was God’s work, not his. The jury, unimpressed, found him guilty and sentenced him to death. He was hanged on the 11th of November. After his death his head was cut off and his body was flayed and quartered into pieces. For years after his skull was exhibited as a curiosity, with many followers of the pseudoscience of phrenology declaring it showed evidence of abnormality.

The biggest impact of Nat Turner’s rebellion was the reaction to it. Slave revolts in ancient Rome had prompted a lifting of restrictions on slaves, allowing a path for them to buy their freedom and passing laws that would prosecute any man who mistreated a slave. The debate in Virginia in 1832 was whether to eliminate slavery entirely, as had been done in several other states, or in whether to continue. They chose to continue and rather than imitate Rome they went the opposite route. The slave-owning politicians decided that education and religion lay at the heart of Nat’s rebellion. Throughout the state it was declared illegal to teach anyone of African descent, slave or freeman, to read and write. In addition the slaves were forbidden from having any religious meetings not led by a white minister. These laws wound up being picked up by all the slave states of the south, leading to an exodus of free blacks to the more liberal Northern states. In fact, the issues of education and freedom of religion became one of the major bones of contention between the two halves of the US.

Turner himself became a controversial figure even up to the modern era, embraced by some as a champion of liberty and symbol of freedom, and condemned by others as a terrorist and murderer. The truth is that he was both. He was a man driven by intolerable conditions to unforgivable acts, one who can neither be condemned or exalted. But perhaps, when we think of the child born into chains, he can be understood.

Banner via.

[1] Such settlements of runaway slaves were known as “Maroon” colonies, taken from the Spanish word for fugitive.