Literature on Film | Lolita Really is Un-filmable – Even Kubrick Failed

Lolita was the first novel I really, truly loved. I didn’t read much as a child. I saw it as a ‘nice’ thing adults asked you to do – like brushing your teeth or eating fruit – something virtuous. I read Lolita when I was 16 and it was completely unlike any other book that had been put in my hands before. It was so many things at once: dangerous, exhilarating, hilarious, romantic, perverse, beautiful, and somehow both cynical and heartfelt at the same time. Best of all – it didn’t have 1-3 easily identifiable themes you could scalpel out, pin down, and dissect in an essay for English class. Lolita doesn’t have a message. It’s a pure slab of experience for the reader, delivered in some of the most luscious prose you’ll ever read. It’s an orgasm of a novel.

‘Unfilmable’ is thrown around a lot, and usually in all the wrong cases – about books that are lengthy, have complex worlds, or very strange / surreal / magical elements – but those challenges are catnip for the right director, just look at Lord of the Rings, Trainspotting, Fight Club. I think looking closely at Lolita shows us what makes a book truly unfilmable.

Lolita has been adapted twice. Stanley Kubrick’s 1962 version is a pop culture fixture via its heart-shaped sunglasses. Much like the status of the film as a ‘classic’, the sunglasses are a case of collective mis-remembering – they never appear in the film (Lolita wears cats-eyes sunglasses) and I’ve always felt that if another name but Kubrick’s was above the title, we’d probably never bother re-watching it. His strengths just don’t click with those of the novel, and it results in one of his few pedestrian films. Along with Adrian Lyne’s soft-core 1997 version, Lolita’s always struck me as a book that can’t – and shouldn’t – be filmed. I could write a trillion words about this, but I’m going to try and keep it brief. As the book is in 2 distinct parts, I’ll address the two separately.

1. ’Lolita, Light of my life, Fire of my loins. My Sin, my soul.’

For the first half of both films, the plot from the novel really sings on screen. Humbert Humbert is a handsome middle aged European academic who’s secretly obsessed with 12-14 year old girls, whom he terms ‘nymphets’. After accepting a new teaching position he moves into the house of a widower, and while she falls in love with him, he lusts after her 12 year old daughter, Dolores Haze (nicknamed Lolita). Kubrick mines this opening setup for some really mischievous and cheeky visual storytelling, developing some new short scenes of his own. Take a look at this 30 seconds scene at a drive-in, where a tiny visual joke succinctly conveys the 3-way dynamic, as well as the attraction to Humbert as a kind protecting patriarch for both of the Haze women.

[arve url=”https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5udVU7aUavA”]

Lyne’s adaptation even has some moments of visual flair – this short little scene on a swing playfully sets up Humbert’s obsession, Lolita’s burgeoning sexuality, and the dull American vulgarity of her mother, Charlotte.

[arve url=”https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uB-BkKOGMd0"]

The one major change to the novel that both directors take is one of timing: both use late scenes from the novel to open the film. Lyne begins with Humbert driving on the wrong side of the road in an empty daze, pursued by police cars. Kubrick begins with Humbert facing off against his nemesis, Quilty, and murdering him in a neat and darkly comic scene which pops with a nervy energy thanks to Peter Sellar’s performance. I can think of two reasons for this. First, starting with a final scene is a handy shorthand in movies to tell the viewer ‘Don’t worry, this story gets somewhere interesting’ and build a sense of mystery. Second, the novel opens with a fake ‘editors introduction’ which sets up that Humbert wrote the long confession while in jail, so in a way the film device fills in this gap of letting us know Humbert ends up a criminal. In Kubrick’s version, one structural bonus of starting this way is that the while the book has two climactic scenes (Humbert meeting Lolita for the last time, Humbert killing Quilty) the film gets to focus completely on the Lolita scene by placing the Quilty scene at the start. So – so far so good for the first half.

2. ‘You can always count on a murderer for a fancy prose style’

The major problems kick in in the latter half of the plot, and here it’s worth talking about the huge stumbling block – the very thing that makes this book great is incredibly difficult to convey on screen: an unreliable narrator.

Humbert Humbert’s tricky narration is central to the experience of Nabokov’s Lolita. He’s a witty, verbose narrator with a high, aristocratic manner and he addresses the reader directly with exclamations and sly winks. Most readers, after about 50 pages, will find themselves on Humbert’s side. He wraps his narrative around you in layers of such sparkling prose that you really do start to feel that this is all just an hilarious romp. He presents the world around him as so dull and vulgar that his witty put-downs set him up as separate and superior. Reading through it again I couldn’t help but think of his droll descriptions of Americana as akin to a glib tweet. Here’s his quick, dry description of Lolita’s house:

‘the kind of place you know will have a rubber tube affixable to the tub faucet in lieu of a shower’.

Just like when you see a tweet mocking the banality of culture, there’s the desire not to be on the side of the mediocre, but with the one who’s looking at it with an arched eyebrow.

For me the character he most resembles in pop culture is Hannibal Lecter. They both have that ability to make themselves appear, despite everything they’ve done, as a pure artistic soul hovering above the clamour of hoi polloi. He even presents his sexuality as simply a refined taste (‘we lone voyagers, we nympholets..’) in contrast to the ‘normal big males, with their normal big mates’. Only seen through Humbert’s eyes, Lolita appears as an otherworldly character – a human embodiment of the ideal he’s been searching for, impossibly bold and yet innocent, vibrating with young sexuality.

As the first half of the book comes to a close, an incredibly unlikely series of events occur that leave Humbert completely free to have sex with Lolita, and he begins a road trip across America with her, from motel room to motel room. The further they travel, an interesting thing happens. Humbert’s command of the narrative begins to falter. There are small moments of rupture, where we get a glimpse of the real Lolita – beneath all the comedy, the intoxicating prose, and the talk of ‘nymphets’ – Dolores the lonely girl, cut off forever from childhood by a delusional and predatory hebephile. The main conflict in the latter half is between these two narratives. Humbert tries to normalise his increasingly deranged and paranoid behaviour, while more and more glimpses of reality begin to disrupt his ‘show’ for the audience, such as ‘her sobs in the night – every night, every night – the moment I feigned sleep’. Meanwhile the reader picks up on recurring clues that show Lolita is engaged in her own narrative, plotting to escape.

When she finally does leave, Humbert’s world implodes. He wanders in search of her for years. As he tells the story of this, his performance breaks even further – we see not only how truly he loved her, but also his increasingly guilt over his abuse.

‘I loved you. I was a pentapod monster, but I loved you…And there were times when I knew how you felt and it was hell to know it, my little one. Lolita girl. Brave Dolly Schiller’.

In the final pages he remembers one moment above all, where he stood above a small town, aware of a peculiar hum, only to realise it’s the sound of children at play:

‘I stood listening to that musical vibration from my lofty slope, to those flashes of separate cries with a kind of demure murmur for background, and then I knew that the hopelessly poignant thing was not Lolita’s absence from my side, but the absence of her voice from that concord’

In a sense there’s an overarching other story happening here. Its the story of Humbert – a talented and manipulative storyteller – confidently performing his past as a comedy to the reader. As he progresses, and as the story becomes darker, his telling breaks down until the reality of his love and his shame breaks through completely. Writing as a performative act of manipulation is key to the experience of Nabokov’s novel.

But this whole ‘trick’ is really challenging to pull off on screen, for a number of reasons:

- It’s hard to show the events you see on screen as being the subjective viewpoint of the hero, rather than an objective photographed reality. Sometimes we see completely unreliable narrators in cinema (Atonement, The Usual Suspects, American Psycho) but it’s a delicate job to pull off a persuasive and manipulative narrator who is subtly authoring what you see to favour them (I’d argue Election and The Wolf of Wall St come close). Neither Kubrick nor Lyne ever make any attempt to capture this, and without this central device, the adaptations seem quite pointless.

- The ‘othering’ of Lolita – the framing of her by Humbert both as a mythic ‘nymphet’ and as a glorious sex object – is key to us losing sight of her as a child. On paper, this works, but on screen you can really only see someone as they are, and Lolita’s sexual relationship always appears creepy because – well, of course it’s right in front of you – it’s clearly a middle aged man and a child, there’s no way to wrap that in ambiguity.

- Humbert’s incredible ability with language is central to our immersion in his narrative. Kubrick’s controlled, confident, direction doesn’t match the passion and exhilaration of Humbert’s style, and the subsequent descent into mania, guilt and lovesick depression. ‘Kubrick opted to downplay style in a text in which style is of the essence’. In Adrian Lyne’s version, everything is either imbued with a sleazy soft-core aesthetic (see here) or the over-scored golden-hued prestige-filmmaking of the 90’s that now plays like an overlong Stella Artois ad.

I might sound really harsh, so it’s worth noting there are some good things about the adaptations. Kubrick’s version does have the gift of Peter Sellars as Quilty. His Quilty is hilariously perverse and chic, with a devilish undercurrent of soul-less evil lighting up his eyes. It feels far too good for the film it’s in. Lyne’s film does best when it deviates, such as when he captures the tedium of Lolita and Humberts conversations between motels.

Overall though, both films takes a complex and emotional reading experience and turn it into a flat comedy-drama, that never does enough to justify its standalone existence. If the book never existed, no-one would have written a film like Kubrick’s Lolita from scratch, because it simply doesn’t work – structurally or emotionally – to convincingly achieve any coherent effect on the viewer. Every year we get Literary adaptations that result in these ‘non-films’ (see this years American Pastoral) that would never be green-lit as original screenplays. Good films are made from good books when the strengths of the book overlap with the strengths of cinema – good plotting, character and/or atmosphere – but when they don’t, we get straightforward adaptations like Lolita, perfunctory and drab.

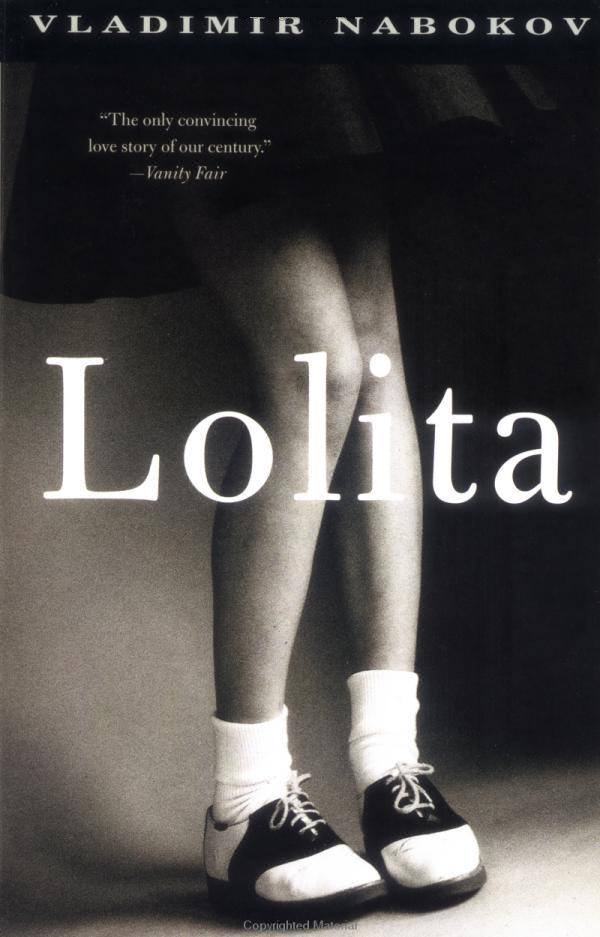

Featured Image Credit