The Other Irish Connection | Barack Obama and Daniel O’Connell

‘Race,’ President Obama said in his farewell address, ‘remains a potent and often divisive force in our society.’ ‘You never really know a person,’ he said, quoting Atticus Finch, hero of Harper Lee’s To Kill a Mockingbird, ‘until you climb into his skin and walk around in it.’

Reminding his audience that ‘the effects of slavery and Jim Crow didn’t suddenly vanish in the 60s,’ he added ‘when minority groups voiced discontent, they weren’t demanding special treatment, but the equal treatment our Founders promised.’

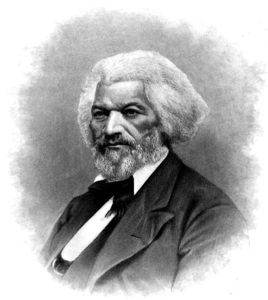

Long before Barack Obama heard of Falmouth Kearney or Moneygall, he had a fundamental connection with Ireland. A deep-rooted political connection that ran from his historical hero, the orator and activist Frederick Douglass, to our own Emancipator, Daniel O’Connell. Obama’s gripping rhetoric, a crucial factor in his election, has a direct link to O’Connell, who achieved real progress, not through rebellion and secret societies, but through elevating with words, masses of disenfranchised Irish Catholics, at his legendary monster meetings.

‘When we strove to blot out the stain of slavery and advance the rights of man, we found common cause with your struggles….’ President Obama told us in Dublin, in 2011. ‘Frederick Douglass an escaped slave and our great Abolitionist, forged an unlikely friendship…… with your great Liberator Daniel O’Connell.

While Frederick Douglass is an icon to students of slavery, Daniel O’Connell’s role has been forgotten. At home, we consider him in purely domestic terms – the man who won Catholic Emancipation but failed in his campaign to Repeal Ireland’s Act of Union with Great Britain. His international reputation, however, was fuelled by the fire of his campaign against slavery.

‘I care not what caste, creed or colour slavery may assume,’ he told voters at an election rally in Kerry in 1831. ‘Whither it be personal or political, mental or corporeal, intellectual or spiritual. I am for its total and instant abolition.’

Not a popular view at the time, his election to the house of Commons caused anger and disquiet amongst MPs who supported slavery. Some would back Repeal, they told him, in return for his silence on abolition. ‘Gentlemen,’ he answered, ‘may my tongue cleave to the roof of my mouth before to help Ireland, I keep silent on the negro question.’ He remained steadfast despite venomous opposition from his main money source – the cash-loaded Repeal Movement in the United States. With ineffable disdain, he returned what he called ‘their blood-stained offerings.’ Leading American abolitionists named their newspaper The Liberator in his honour.

A celebrated speaker himself, Benjamin Disraeli spoke of ‘the thrilling tones of O’Connell.’ and he could thrill in many languages. Charles Dickens, then a parliamentary reporter, considered most politicians ‘pompous,’ speaking ‘sentences with no meaning in them,’ (no change there) but not O’Connell. Dickens was compelled,’ he said, to down his pencil, as tears flowed when the Member for Ireland spoke. Words were O’Connell’s weapons, carefully selected to express misery, defiance, determination or hope. He flavoured his sentences with alliteration, comic similes and kept his audience rapt with dramatic anecdotes. Also, he looked the part of a charismatic leader. Over six feet tall, muscular and massive – he was a towering Hercules.

As a young slave in Maryland, Frederick Douglass heard his master curse Daniel O’Connell’s anti-slavery views, so Douglass loved him. Having taught himself to read (illegal for slaves), he found a copy of The Columbian Orator, which included O’Connell’s speeches on Abolition and Emancipation. He devoured those speeches. From them, he developed the pace and pitch, to shape and utter his thoughts on slavery and social justice. They formed the bases for his future compelling rhetoric.

Vividly described in Colum McCann’s novel TransAtlantic, Frederick Douglass arrived in Ireland just as the despair of the famine was descending. He had lately published his autobiography, Narrative of the Life of… An American Slave. Because he hadn’t disguised his own or his master’s identity, he feared slavecatchers and so he fled. Tall, dark-skinned and exotic, he travelled Ireland speaking in support of the Abolitionist Cause. Astonished at the openness with which his colour was received, he wrote home:

‘No one seems to find himself contaminated by contact with me…no nose grows deformed at my approach.’

With his mastery of narrative, he by turn, enthralled and shocked his Irish audiences. ‘Flinty hearts were pierced and cold ones melted,’ was how one newspaper described his impact. The highlight for Douglass, however, was hearing O’Connell speak in Dublin. ‘His eloquence came down upon the vast assembly like a summer thundershower on a dusty road.’ Douglass said.

To his delight, his hero invited him on stage, introducing him as the Black O’Connell of the United States, a sobriquet Douglass would proudly wear – forever linking the two.

As January 20th approaches and we say goodbye to President Obama, to his riveting rhetoric and dynamic power of persuasion, we Irish salute him for reminding us of a chapter in our Irish- American history that we had so shamefully forgotten.