Safe Ireland Summit 2016 | Shifting the lens on Violence Against Women

At the Safe Ireland Summit last month, Linda Hamilton Krieger invited us to consider how we frame the issue of Violence Against Women (VAW). Krieger is a US civil rights lawyer, immersed in the everyday practice of the courtroom, and highly critical of it. She reminded us of the standard frame that defined VAW for centuries, which involved leaving it out of the frame altogether. Violence, especially domestic violence, was something that did not happen, was not discussed, something that wasn’t real. Alternatively, VAW can be framed in the sphere of interpersonal relations, something that happens, but is private and personal. When violence occurs, we remember, there’s always a pair of them in it, and probably things just got out of hand.[pullquote]Violence, especially domestic violence, was something that did not happen, was not discussed, something that wasn’t real.[/pullquote]

The feminist movement succeeded in shifting the frame, and ensuring that Violence Against Women was seen as a matter of public concern. Over the course of two days at the Summit, a new debate was exposed: what frames are now available that address VAW as a public concern, and what difference do these make? The Safe Ireland Summit was a rich, deep immersion in many ways of thinking about Gender Based Violence, and many of the contributors made important progress on this theme. How can we change the frame?

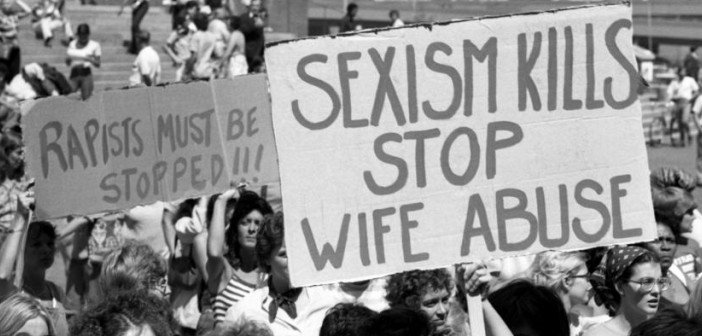

When the battered women’s movement emerged in the 1960s and 70s in the US, they drew attention to a violence that was ignored, and they demanded its recognition as an injustice on par with any other criminal offence. The first Violence Against Women Act was signed into law in the US in 1994, a major touchstone for American activists. Leigh Goodmark, another legal scholar, remembered the feeling of triumph for feminists when they succeeded in making domestic violence a criminal justice issue. The 1994 VAW Act is a touchstone for activists in the US, and indeed the world. It unquestionably resulted in an increase in arrests and prosecutions for domestic violence (DV) crimes. But as much as this was a political triumph, it has had unintended impacts.

When you frame violence against women as a private issue, you make it impossible to prevent, or even offer a response. When you frame it as a criminal justice issue, you squarely locate the blame and responsibility on the defendant, constructing him (it’s usually a him) as deviant, and everybody else in society as normal. Leigh Goodmark offered five unintended consequences of the DV Act and its criminal justice focus.[pullquote]When you frame violence against women as a private issue, you make it impossible to prevent, or even offer a response. [/pullquote]

First, arrest rates went up – especially among women. This happened in part because of the false equivalence that plagues DV legislation around the world, insisting that both women and men may equally be victimised and be perpetrators. But it also happened because in cases that were complicated and knotty, the police – mandated to carry out arrests – would arrest both members of a couple. Battered women found themselves in jail.

Second, as a result of increased police involvement in women’s lives, women found the state encroaching in ways they had never expected. Women who needed protection from an abusive partner found themselves subject to child welfare investigations, addiction services, and other interventions that neither improved their well-being nor increased their security. In effect, involving the police amounted to an invitation to state officials to target women in a discriminatory fashion – as poor women or as black women. Most women who experience violence in the home don’t want their entire lives to change. They just want the violence to stop.

Even on its own terms, criminalisation is at best a partial response. When it defines the nature of the response, it distracts from victims’ rights. The VAW Act guaranteed generous resourcing for the justice system – to the exclusion of other areas that desperately needed resourcing: mental and physical health services for women survivors; housing; childcare; and many others. There is nothing fundamental to a criminal justice response that precludes investment in other, equally important areas, but when priorities must be set, the legislation is clear on where the priority lies.

In other ways, a criminal justice response can run directly counter to the needs of victims. It draws attention to legal process norms: “innocent until proven guilty”; the right to a fair defence. These are crucial norms within the criminal justice frame, but ones which focus entirely on the rights of the accused, and ignore the victim. Evidence law often makes victims feel silenced, or worse, attacked and retraumatised.[pullquote]Most women who experience violence in the home don’t want their entire lives to change. They just want the violence to stop.[/pullquote]

Besides, the only place a perpetrator in a criminogenic system can end up is in prison. As Goodmark pointed out, a disproportionate number of perpetrators of violence are poor and unemployed men, just as a disproportionate number of victims are poor women. When perpetrators are imprisoned, they eventually emerge poor, unemployed, and stigmatised: they fit the profile of an abuser even more perfectly. While women pushed long ago for accountability, the punishment societies came up with does nothing to break the cycle of violence. What’s more, we know that violence perpetration is often intergenerational, learned through norms that are absorbed within abusive families or violently unequal communities (or both). At the Summit, John Lonergan and Gabor Maté both introduced voices from prisons. They spoke powerfully of the ongoing transmission of trauma, and the failure of the criminal justice system to halt the damage and violence that is an outgrowth of trauma.

As Linda Hamilton Krieger highlighted, the criminal justice response is an individual one: it places responsibility on the individual, and does nothing to tackle the structural nature of Gender Based Violence. Individual acts of violence occur in a context of inequality, discrimination, and structural violence. Experts in Gender Based Violence globally talk about an ecological model of violence risk: threats and dangers come not from isolated individuals, but from the complex interaction of social and environmental factors, overlaying psychological and personal historical elements. The ways that we think about accountability need to go beyond the individual – not to absolve the individual of responsibility, but to get to the root causes of the problem instead of endlessly firefighting.

How can reframing Violence Against Women make a difference? Clearly, shifting from a frame of privacy to criminal justice was a huge leap, but one which came up short in numerous ways. A public health frame might offer a new way of addressing the issue. It offers an ecological model for understanding Violence Against Women – that is, it acknowledges that violence has both individual and environmental determinants. So it locates the problem in society, as well as with the individual victims and perpetrators.[pullquote]While women pushed long ago for accountability, the punishment societies came up with does nothing to break the cycle of violence.[/pullquote]

Krieger discussed an approach to restorative justice practiced in Hawaii: a traditional system of justice called Ho’oponopono, which has evolved into a modern interdisciplinary court. It holds, in the first instance, that offenders must be held accountable and victims must be protected; yet it recognises that perpetrators are products of the harms in their lives. Thus, the approach taken to accountability is broad: it includes anger management, specialised training, and reparation as well as custodial elements. The courts work with communities in order to ensure that citizens are aware of how VAW is viewed, and how it is addressed, so that they will view the courts as a resource. In order to bring about such a nuanced approach, the courts are staffed with specialists: judges, police, attorneys and even officials. Gabor Maté talked about trauma healing, and addressing the root causes of individuals’ violent behaviours; John Lonergan discussed innovations in prison management that respect the personhood of perpetrators, their vulnerability as well as their crimes.

A new approach to VAW is clearly called for, but I’ve seen the gap between inspiring talks and complicated interventions many times. When pushed for policy recommendations, Gabor Maté insisted that what was required was not specific policy changes as much as an attitudinal change. That is what a shift of frame is – a move from one way of understanding a problem to another. I’m left pondering the policy implications of this sort of frame change. Arguably, it needs to begin with victims’ rights, investing in victim support and above all not putting survivors of violence through retraumatising adversarial court showdowns. The changes required ripple far beyond services for victims, or even reform of criminal justice – although these are essential. Violence in the home is connected to the availability of affordable housing, dignified work, timely healthcare, and quality childcare, to name just a few elements. A shift to a public health frame involves much more than individual services. Perhaps this is why it’s such a difficult shift to achieve.

Meanwhile, behind the impressive, sensitive, holistic understanding of human trauma and vulnerability, we must not forget that at the end of the day, those who seek to end violence against women seek to take excessive power away from some men. We don’t get to create an ideal system from scratch: some righting of inequities must be done, with all the anger and rage that this brings up. The backlash is powerfully underway against the very feminists who first succeeded in reframing the issue: this was the dominant theme of the Summit, echoes of Trumpian hatred tracing through many speeches and working their way into twitter threads.

A systemic response to violence against women would connect with many of the other social justice challenges of our time. A compelling argument in its favour is that nothing else seems likely to work.

Carol Ballantine will be chairing Responses to Gender Based Violence in Dublin on Wednesday, December 7th as part of the International 16 Days of Action Campaign Against Gender Violence.