What We Don’t See | How Absence and Omission Perpetuate Bias in Documentary Filmmaking

Are all documentaries inherently biased?

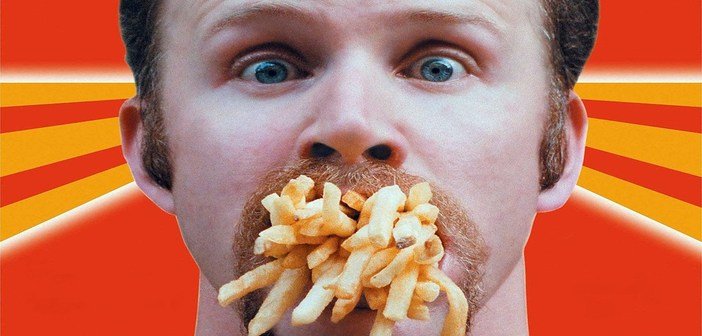

We are all well-versed in the topic of bias in documentaries and whether or not they can be deemed legitimate sources for accurate information. The question involving the reliability of documentaries is constantly being interrogated. We just have to analyse highly successful ones such as Morgan Spurlock’s Supersize Me to know that they don’t always tell the whole truth. In this documentary, there were some discrepancies involving the results of the overall experiment and the comedian, Tom Naughton even made a follow-up documentary entitled Fat Head in an attempt to expose these alleged falsified results.

Sometimes, through viewing a documentary, it can be obvious which side a filmmaker favours. However, the unavoidability of bias in documentary filmmaking is ubiquitous. It doesn’t have to be intentional, but bias is present in every documentary you see, no matter the subject matter or topic. Participatory-style documentaries, such as Supersize Me, can make bias harder to detect as the filmmaker is actively taking part in the topic rather than passively filming and observing it from a distance. For the most part, what is left out of any documentary perpetuates the bias within it. It doesn’t even have to be omitted, it just has to be absent. Whether it’s intentional or not, what we don’t see is a key contributing factor towards bias in any given documentary.

The Lovers and the Despot

As part of the IFI Documentary Film Festival 2016, the final screening was a documentary based on the experiences of actress, Choi Eun-hee and her husband and director, Shin Sang-ok who were allegedly abducted from South Korea by Kim Jong-il and held captive in North Korea. Kim Jong-il was reportedly very fond of filmmaking and was frustrated at the fact that North Korean films were rarely recognised internationally. The story goes that he set out to abduct a famous South Korean couple: an actress (Choi) and a director (Shin) in order to capitalise from their acting and filmmaking abilities, giving them creative and financial freedom in return. The Lovers and the Despot was directed by Ross Adam and Robert Cannan and while the tale itself is fascinating, it is one that would probably fare better on the silver screen. The content of this particular documentary is a prime example of omission as we are left with more questions than answers after viewing it. What we end up with is rather in-comprehensive and inconclusive. While the documentary itself was filmed and shot very well and the reconstructions are credible, the only real, hard evidence we are given is the voice recordings Choi brings along to her interview. We are completely reliant on Choi’s accounts of what happened and the audio recordings, with some CIA agents from the United States and South Korea giving their own accounts here and there.

But the subject matter in itself is problematic. It involves at least three primary subjects: Choi, Shin, and Kim Jong-il, one of which is deceased and another is, well, the leader of North Korea. When deciding to film a documentary about this kind of story, evidence is key. Political documentaries need to give all parties involved a voice in order to give an unbiased or semi-unbiased account of what actually occurred. Otherwise, what we are left with is an inconclusive audio-visual story, which is fine to an extent. But unfortunately, this particular documentary fell short on evidence too often. Recordings, particularly audio ones, are not enough to pass as sufficient when it comes to supplying the audience with enough evidence to make an informed decision or even an informed opinion. It felt as if the filmmakers were trying to give the spectators the opportunity to decide for themselves whether or not Shin was in fact kidnapped, but without his own personal account of what happened in an interview similar to that of Choi, it’s almost impossible to decide for ourselves.

We are also denied the opportunity to see the scene of the crime. Instead, we are given reconstructions of the alleged abduction. However, the reconstructions are based predominantly on Choi’s memory of what happened almost thirty years previous to the interview. And as the filmmakers were not granted access to North Korea, the audience are denied even more crucial evidence. The Lovers and the Despot is certainly a compelling story, but with so much absence and uncertainty, is a documentary really the best format to tell it?

Amanda Knox

When it comes to political or crime documentaries, is it easier for an audience to detect who the filmmaker is encouraging them to sympathise with? When we analyse documentaries such as the Netflix original Amanda Knox (2016), directed by Rod Blackhurst and Brian McGinn it may not appear to have omitted as much as the previously discussed documentary, but is nonetheless problematic when it comes to detecting bias. It documents the conviction and imprisonment of the then twenty-year-old American student, Amanda for the murder of Meredith Kercher in 2007. Amanda was an exchange student residing in Italy at the time and consistently proclaimed her innocence throughout her trial, imprisonment, and present life as a twenty-nine-year-old. It becomes clearer as the documentary progresses who the filmmakers want to, intentionally or unintentionally, “look bad”. Journalist, Nick Pisa is definitely in that category and the filmmakers certainly succeeded in that endeavour whether it was premeditated or not. The documentary makes it appear as though Amanda was wrongfully accused and convicted by a corrupt Italian supreme court. They also made it abundantly clear that this was a media-fuelled murder trial and that when it came to analysing actual evidence, Amanda’s unusual “behaviour” was privileged over DNA evidence by the police.

The fact that Meredith is not present obviously cannot be avoided since it is her murder of which Amanda was convicted. The main omission or absence, however, is that of Rudy Guede. Rudy could not be interviewed because he was ultimately convicted as the sole murderer and was sentenced to thirty years in prison. As with The Lovers and the Despot, at least two primary subjects involved in the subject matter are absent here. However, as this particular topic is predominantly centred around the media and the Italian justice system, this is almost forgivable. It is clear the documentary as a whole is attempting to depict the Italian justice system as one that is steeped in conspiracy and corruption and that tabloid journalists are malicious people who would write anything and everything to uncover a decent and, more importantly, an exciting story. The stylistics of the documentary involve flashy tabloid headlines juxtaposed with dramatic shots of different interviewees, making it appear almost as a fictitious piece of filmmaking, rather than a documentary.

Can we trust documentaries to tell whole truths or must we be content with partial truths?

Of course, including every point of view on a topic in one hour-long documentary is going to be impossible. We can’t know absolutely everything about one subject and documentaries are accurate reflections of that. Omission and absence are not the only influencers when it comes to bias in documentary filmmaking either. There are many other factors that contribute to unintentional bias; even generic factors such as cultural background, race, and gender. For example, the directors of The Lovers and the Despot are two white, British males, but what if they were South Korean women or North Korean men? It is likely that if their cultural backgrounds or genders were different, the outcome would have been completely different, and the same goes for their bias.

So should we really rely on documentaries to give every ounce of information? Should we even trust that they are telling the truth? The most important thing we should remember is that documentaries simply cannot include everything and what is absent from them could be the difference between a whole truth and a partial truth. What we don’t see might just be exactly what we need in order to change our minds.

Feature Image Source