Space Week | From Science-Fact to Science-Fiction, Space Films Show Us Mankind’s Obsession with the Stars

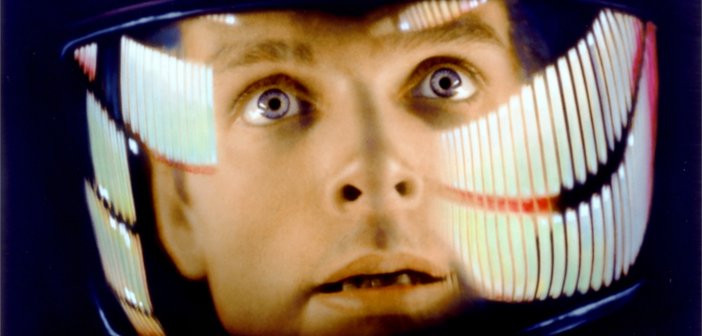

2001: A Space Odyssey (1968), Dir. Stanley Kubrick

In many ways, what is there left to be said about 2001? With the exception of Citizen Kane and a handful of others, there are very few films which have had as much ink spilled over them as Kubrick’s eponymous ‘Space Odyssey’. People who’ve never seen it – hell, people who don’t watch movies – could likely still hum ‘Blue Danube’ or ‘Thus Spake Zarathustra,’ and even if they couldn’t, would immediately imagine floating carefree in zero gravity if they heard them; so deeply ingrained is its mark on popular culture. More impressive than its endurance as a point of reference for almost anything in fiction that dares venture off-world though, is that even today it still works. Especially if you can find yourself lucky enough to be seeing it on the big screen as intended.

Kubrick’s trademark, painstaking research of the science of space-faring remains believable (and to date, almost no film has the integrity to show space in all its terrifying silence like the tenser sequences of 2001 do), the music still manages to evoke chills, the star-gate sequence has lost none of its majestic, unnerving awe and the ending retains the capacity to incite arguments. When it does lean on the “fi” side of the genre, it goes all out, but an impressive amount of the film is admirably close to science-fact. Why else would practically every space-related movie which followed it be unable to avoid referencing and calling back to it? It visualised space and space travel with a level of authenticity that few have surpassed, bar perhaps actual NASA footage, while simultaneously, almost clairvoyantly, nodding towards everything from military satellites to tablet computers, while firmly establishing a distrust of A.I.’s that we as species are unlikely to overcome. And all this with a running time less egregious than most modern blockbusters, very few of which can claim to cycle through the dawn of man right up to the end of our species and the birth of a new one.

The Andromeda Strain (1971), Dir. Robert Wise

Based on a Michael Crichton novel of the same name, The Andromeda Strain deals with the possibility of an alien pathogen hitching a ride to our planet and the devastation it might cause. ‘Project Scoop’ find themselves in possession of a deadly, foreign, airborne contagion that kills almost everything, almost instantly. Clotting your blood, turning it to powder and melting your skin from your bones; The Andromeda Strain is not something to mess around with.

Robert Wise’s adaptation is a slow-build thriller, utilising flashing lights, sirens and clean, futuristic sets to create a sterile yet ominous atmosphere. The graphics are pretty stellar too, for its age, with Douglas Trumbull, of 2001: A Space Odyssey fame, at the helm of creating the hyper-futuristic computerised visuals.

With the real possibilities of bacterial life surviving in space and entering our atmosphere on the back of a meteorite or satellite, with many believing that is just how life on Earth began, the plot of the movie is, although unlikely, definitely plausible. The bio-weaponry subplot that raises its head in the second half of the movie raises more questions in today’s turbulent world. How ready are we possible attacks? What are the procedures in place for such events and just how much have the government got to do with it?

Gattaca (1997), Dir. Andrew Niccol

[youtube id=”m_nkVmRSpfE” align=”center” autoplay=”no” maxwidth=”750"]

While significantly more Earthbound than the other films mentioned here (indeed, none of it takes place in Outer Space) Gattaca warrants inclusion as it poses the question of who is better equipped for space exploration: the naturally talented or the hard worker.

Set in that familiar time, the not too distant future, Gattaca explores a world where eugenics has become standard and genetic selection means most children are designed with their parents’ best genes. Ethan Hawke plays Vincent, an “invalid” (someone born by traditional means) who dreams of going to space but is prevented by his greater health risks. So he assumes the identity of Jerome, a paralytic who donates samples of his genetic material so he can pass the DNA tests. Working hard, his dreams are in reach, however a murder in the office places everyone under intense scrutiny.

Featuring an excellent cast including Uma Thurman, Jude Law and a lovely Frank Lloyd Wright building, Gattaca is an interesting discussion on the ethics of genetic engineering wrapped in a glossy thriller, as well as a fun look at how space travel would operate at ground level in the future. Out of the cast, Jude Law’s Jerome is especially enjoyable as the snarky source of Vincent’s deceit.

Today, there is much discussion on manned missions to Mars and the human sacrifice involved. For us, Vincent represents the determined individuals who will make it there, people with no need to turn back.

Contact (1997), Dir. Robert Zemeckis

Based on a novel by writer and science populariser Carl Sagan, Robert Zemeckis’ 1997 film Contact is often heralded as a sci-fi that strived for an authenticity in regards to its science. It stars Jodie Foster as Dr. Ellen Arroway, a scientist for the SETI institute (which is an actual organisation dedicated to searching for extra-terrestrial intelligence) who is tasked with decoding signals sent from the star system, Vega, 26 light-years away. The messages are revealed to be the plans for a device that can travel through wormholes, possibly linking a race of aliens with Earth.

From the outset, one can tell certain elements of Sagan’s fantasy are rooted in fact. The signals being received from Vega (which is an existing star) are specifically noted as being “radio waves”. If an alien species did try to contact earth, it would make logical sense to use this method. Radio waves can move at the speed of light, transfer vast amounts of information and travel long distances.

Although wormholes only exist theoretically, Sagan drew upon scientist Kip Thorne’s studies of the phenomenon to present them as realistically as can be imagined (Thorne later became a science consultant on Christopher Nolan’s Interstellar). On top of this, the film’s protagonist Dr. Ellen Arroway is based upon the true life figure of Dr. Jill Tarter, head of Project Phoenix (a team searching for alien intelligence through analysing patterns in radio signals) at SETI. It’s reported that Tarter actually consulted with Sagan and Foster. This was in order to help the movie portray accurately the struggles women scientists face in their profession.

Sunshine (2007), Dir. Danny Boyle

From all of the films picked for space week, Sunshine feels, in some respects, to be the most nonsensical. The central plot, to jump start the sun by dropping an atomic bomb in it’s centre, contains echoes of that episode of Futurama where the team come up with the brilliantly daft idea to combat climate change by dropping a giant ice cube in the Atlantic ocean.

The film recruited Brian Cox (the keyboard player from D:REAM, not the actor) as a consultant, and much of the cast brushed up on their physics in preparation for the film. Danny Boyle is even said to have deleted a sex scene, on the basis that the act would be literally impossible in space. Despite all of these measures, there’s still the utterly ridiculous central conceit of the film, that you can literally bomb the sun into working. At the same time though, isn’t that sort of what space week is all about? If space travel is indicative of anything it’s that humanity is pretty awesome. Who says we can’t restart the sun?

Moon (2009), Dir. Duncan Jones

[y[youtube id=”Cb3exxD2nGo” align=”center” autoplay=”no” maxwidth=”750"]p>

Moon is about the mundanity of space. It’s not a film that tries to tell us we aren’t alone or that we occupy a privileged position in the galaxy, rather it is content to be blunt and tell us that as soon as big business finds a way to make money in space, it’ll be reduced to just another pretty vista where small blue-collar cogs will work for the big machine. Positioning Sam Rockwell’s Sam as a sort of one-man oil-rigger (but with the rig in this case being the moon), the director-formally-known-as Zowie Bowie’s film follows Sam during the final weeks of his three year stint mining helium-3 from the lunar installation.

Aside from being an entertaining and engaging existential drama, the film is also probably one of the more reigned in visualisations of a space-colonising future. The insidious and dehumanising way Sam’s very life and autonomy are treated by the corporation employing him (if ‘employment’ is the right word, given the film’s revelations) feel entirely too believable. The callous level of disregard for sentient life in favour in the lowest cost mining techniques is true to the reality of our own late capitalist society but it’s not hard to picture the extremes taken in this film being utilised today were the technology available to be abused in the manner the film demonstrates.

Being a fairly low budget, debut film, CGI couldn’t be relied upon as heavily, so in order to save money more old school techniques were utilised. The robot is practically designed and un-showy, the absolute most is made of the limited sets and for the all-important lunar surface excursions, miniatures were heavily employed.

Interstellar (2014), Dir. Christopher Nolan

Space exploration feels like a natural progression for Christopher Nolan after the science-fiction heist epic Inception, and the ground-breaking Dark Knight series. Although he deals with high concepts such as the subconscious and superheroes, the director endeavours to root his films in some form of grounded reality. Interstellar is no exception, and so he enlisted the help of astrophysicist Professor Kip Thorne to help accurately depict the film’s science.

The film stars Matthew McConaughey as Joseph Cooper, a former NASA pilot, who with a team of scientists volunteers to search for habitable planets in a distant galaxy, after an earth ravaged by the throes of global warming becomes increasingly unsustainable. They reach the other galaxy via a wormhole that had appeared near Saturn 48 years previously, wherein scientists from a previous mission have sent back encouraging data from a planet near a black hole called Gargantua.

The characters in space age at a different rate than people on earth. In one sequence, a tearful McConaughey watches videos of his daughter age from childhood to adulthood – a period of 23 years – while only a few hours have passed for the scientists on-board the ship. This is one element of the film that has basis in science fact as opposed to science fiction: astrophysicist Neil deGrasse Tyson claims Interstellar depicts Einstein’s Relativity of Time better than any other feature film. However, there are criticisms of the film’s accuracy, particularly in relation to how it depicts a ‘gravitational slingshot’. In order to avoid being sucked into Gargantua’s pull, the crew decide to propel the ship toward a nearby planet by pushing it to a high speed. In reality, the speed required to pull off such an act without flaw would need to be close to the speed of light, and would therefore tear the ship apart. Not an ideal ending for a Hollywood blockbuster, then.