“… Something that might do some good” | A Conversation with Writer Donald Quist

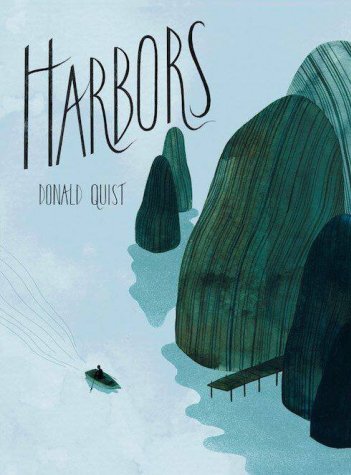

Donald Quist trusts in the clarity and outlook of his talent, which has emerged in a myriad of roles: fiction writer, playwright, reporter, podcast host and educator. Only recently has he focused his efforts on telling his own story. Harbors, published in September by Awst Press, is a series of essays following Quist’s childhood in Washington, DC to his eventual expatriation to Thailand with his wife. A memoir in fragments, it describes a coming-of-age story under the looming banner of American racism. Parallel to this though is Harbors as the Künstlerroman of a young artist drawing himself out of a nation of contradictions, defining himself anew in a space where he is so easily dismissed as a stereotype (or not stereotype enough) and forgotten.[pullquote]The essays are as troubling as they are beautiful. America was never so naked as when Donald Quist records how it has hypocritically spoken of itself, how its necessity to save face has disenfranchised a large section of its citizenship.[/pullquote]

I’d known of Donald for several years. We’d send stories back and forth and he was always nice to provide his insight. When he asked me to write a review of Harbors, I was deeply humbled. Reading it, I am ever more so. The essays are as troubling as they are beautiful. America was never so naked as when Donald Quist records how it has hypocritically spoken of itself, how its necessity to save face has disenfranchised a large section of its citizenship. In fact, Quist’s book at one point asks what it could possibly mean to be an American citizen and an African American? The two, it seems, are incompatible. The doublespeak of white discourse creates stultifying, invisible walls that create the very inequality that many white Americans dismiss as the exaggeration by minority communities. Quist confronts it head on. Reading his work was an epiphany, a call to response. You can’t leave his work unscarred.

However, it is reductive to call Harbors a political work. Quist is an artist and all of his experiences contribute to the forming (and the continual formation) of his aesthetic. His experimentations with the non-fiction genre as well as with the form of narrative show a writer who plays jazz with the written word (a la Colson Whitehead) but maintains an undeniable depth and urgent meaning to his work (consider Toni Morrison). So, it’s with his art that I wanted to begin.

Nick Hilbourn: I primarily knew you as a fiction writer, although I’d heard you mention dabbling in screenwriting and poetry before. Despite this, non-fiction still seems like an extraordinary leap to me. What provoked you to begin writing non-fiction?

Donald Quist: I’ve been writing essays since I was an undergrad, but I never felt entirely confident in my ability as an essayist. After moving to Thailand a few years ago I spent a lot of time in my own head. Being so far away from my family, friends and country, the isolation prompted me to review these relationships and gave me distance to delve further into my understanding of these affiliations. As pieces started to form and Harbors came together, I became more assured in these narratives.

NH: Did you find it harder to write non-fiction?

DQ: I find aspects of writing non-fiction easier. I usually spend less time plotting or crafting characters. But it can be very difficult to balance a sense of responsibility to the truth and a desire to be compassionate to the subjects of the story I’m trying to share.

NH: That’s true. In Harbors, I was intrigued with how you played with the form of the essay. I was curious if that might have had anything to do with attempting to balance that responsibility to the truth with your compassion for the subjects you’re describing?

DQ: I suppose a desire to be considerate did shape the form of many pieces. The form always comes from how I want the narrative to function. In the case of one essay called, “In Other Words”, perspective switches between me and the imagined viewpoint of my spouse. This decision came about because I didn’t feel like I had a right to dictate what my partner was thinking – to so confidently impose my perception onto someone I care about. I didn’t invent her; I can only make assumptions based on empathy. I can only try to know what she felt or thought in the moment I am trying to recount on paper. So, the narrative evolved into an envisioned conversation and the essay very much acknowledges that my memory and perception is limited.

NH: I’m glad you mention empathy because I know one of the things I’ve often heard you say is that you’re trying to become a better person as well as a better writer. Personally, I think you must develop empathy in order to be a good writer, to create anything outside of a solipsistic landscape. Harbors, to me, reads like a process of development, a therapeutic act, even a catharsis. A trope I saw in many of the essays was the act of organization and how important that seems to have been in your maturity. James Salter, for example, spoke of the importance of personal journals in focusing and deepening his content. Do you journal and, if so, how do you journal? (Daily or sporadically, how detailed, is it just prose or do you draw? etc.) and to what extent do your journals (if you do them) play in forming the content of your essays?

DQ: I do journal, although not daily. I’ve always carried a journal and I do set aside some time each week to write down things I find worthy of note. I fill the pages with scraps of story ideas, crude illustrations, diagrams, brief recollections and reflections on books I’m reading. It’s not very detailed and it’s unruly, but it helps me make sense of things. This habit has been very helpful in my writing. Mostly all of my creative writing first forms on the pages of my journals. While working on essays for Harbors it was very helpful having these diaries to reference different periods in my life.

NH: We’re both teachers and I feel like that kind of job gets into your bones, gets into your blood. It saturates the rest of your life. It’s unconscious. You do things differently, with a different intentionality. Harbors, to me, carries a pedagogical tone to it. It’s not demeaning or belittling, but compassionate and careful. I’m specifically speaking of “Til Next Time”, an essay about your grandmother and “I’ll Fly Away”, your meditation on American racism. These are essays where I felt like you were teaching me by example, where your organization seemed to draw attention to certain details that I should pay attention to and think on carefully. In terms of this, what did the process of writing Harbors teach you? In what ways did you grow from the writing of it? Also, do you feel that your essays have this pedagogical element to them? If so, was it intentional or did it occur to you afterward as you were editing?

DQ: I’m not sure what the process of writing Harbors has taught me. I think I’m still figuring out what I’ve learned from putting this book together—forgiveness seems to be part of it. I’ve definitely grown from writing Harbors; it forced me to address unresolved issues with people I love and places I’ve called home. There were a lot of emotions I had buried that we unearthed while writing. It was hard to slog through all of that muck, but I feel better for having done it. I suppose all essays are written to be informative; the writer is attempting to share something with the reader, right? They are trying to give knowledge. I approached Harbors the same way I do a classroom lesson plan—I’m trying to be informative, to share my knowledge about a particular aspect of humanity without appearing boring or didactic. So the essays do have a pedagogical element, although I didn’t really think about it until you asked me. A particular piece is in the form of a lesson plan for one of my academic writing classes. I chose this form because I thought it is best suited for what I wanted to do, which is to provide a physical representation, an example, of the process of seeking and then giving greater perspective. That’s teaching to me.

NH: You mention “home”. As I considered many of the issues your essays raise I was reminded of an essay by Edward Said, “Reflections on Exile”. He speaks about the ontological problems and/or etiological issues of many who have been forced to (or, forced to choose to) flee encounter. In the essay, Said references Theodor Adorno, who said that the only home available to him now was through writing. Have you found this true for yourself?

DQ: First, love that quote! I find this completely true. I have never felt a sense of home anywhere. I have yet to encounter a physical location I feel tied to, a place where I feel a complete sense of belonging. I’m always looking for an exit, no matter where I go, always on guard, only more so in the United States. But I don’t feel that way on paper. When writing, I’m at home, I feel most safe to be myself. I get comfortable, like sitting-in-a-house-with-no-pants-on comfortable, like, dancing-naked-comfortable. As reviews for Harbors come in, I’m surprised to have this vulnerability analyzed and explained back to me. I wrote the book like I thought no one would ever really read it. I scratched the places that I keep covered when I’m out in public, ripped open the scabs under the armor I have to wear while navigating the places I feel most afraid. And now there’s this record of it getting distributed across the globe. It’s scary, exciting, cathartic and humbling.

NH: You mentioned “forgiveness” above. Who (or what) are you forgiving and why was forgiveness so important to process of forming Harbors?

DQ: I think forgiveness is a powerful thing. It’s not easy, right? And I’m not trying to proselytize. I’m a very angry person. Many wouldn’t know this just by looking at me. I internalize a lot of things on a daily basis, and I’ve compartmentalized a lot of things from my youth. This tendency has led to sporadic, violent, explosions. I came to a point where it was crucial for me to learn to forgive, not just others, but myself—most of my anger is directed at myself. After so many years of this, it was becoming apparent I was going to eventually do something incredibly destructive. I’d inevitably hurt someone I care about or kill myself.

For me, forgiveness became a necessary means for the preservation of life. Moving to Thailand helped. The physical distance allowed me greater perspective. I set out to write about these personal revelations and forgiveness was a result of the process. Writing through things, deconstructing my relationships with family and friends, and my relationship with my country, helped me learn to forgive.

NH: Yes, of course. There are specific gestures of forgiveness that I find in “Junior”, an essay about your father. It was as touching as it was perplexing: “Is he forgiving his father?”, “Is he forgiving himself for his youthful misunderstanding of his father?”, “Is he forgiving them both for their equal mis-readings of each other as a kind of reconciliation?”

DQ: In the case of the essay “Junior”, the piece took the form of a letter I’d never send to my father. And yes, in that essay I’m forgiving my father, I’m asking him for forgiveness, and I’m forgiving myself. Harbors is my attempt at reconciling my existence. So, whatever happens with this book it has succeeded in this goal. I’m better for having written it and I hope others find value in the book as well. I hope it helps them in some way.

Of course, I’m still an angry person. I’m not sure I could ever be at peace with the knowledge that every day so many people are suffering from shit that could/should be preventable, that every day people are struggling against oppressive constructs associated with gender, race, nationality and class. And I’m maddened by my own ineffectiveness in fights against hierarchies I often benefit from. And then I feel furious for not being more appreciative of what I have. But, like I said I’m learning to forgive more, while working to turn that rage into something productive. I’m trying to turn that scorching fury in my chest into something that might do some good. I’m doing it the best way I know how.