Canal Bank Misadventure: Kavanagh on the Grand Canal

In Greek mythology, the source of all wisdom passed down through verse, lyric and myth can be traced back to the nine muses, and their residency atop Mount Parnassus. In ‘Lines Written on a Seat on the Grand Canal Dublin’, Patrick Kavanagh suggests the waters of Dublin’s most famous waterway are home to “Parnassian Islands.” Former students of Leaving Cert English will know well that the canal banks are the site of Kavanagh’s creative rebirth, during his recuperation from Tuberculosis. Less is known of an incident in 1956, when the poet was lucky to escape with his life. Details are scant, though a few figures loom large: principally a bevy of of the poet’s frenemies from the criminal ‘underworld.’

Making his way home from a round of drinks, Kavanagh was in good spirits when a car pulled up alongside him. The late Antoinette Quinn, author of the most comprehensive biography of the poet to date, offers the most coherent account of the event, relating the incident as it appears in a (personal) letter to a solicitor at the State Solicitor’s Office. Amongst the men in the car was Dinny Dwyer who asked Kavanagh whether he would like to stop for drinks in a nearby flat. Dwyer and Kavanagh had not spoken since the publication of an article Kavanagh had written in the Farmer’s Journal. Dwyer’s invitation was intended to heal the wound, as they would reconcile their differences and talk about old times.

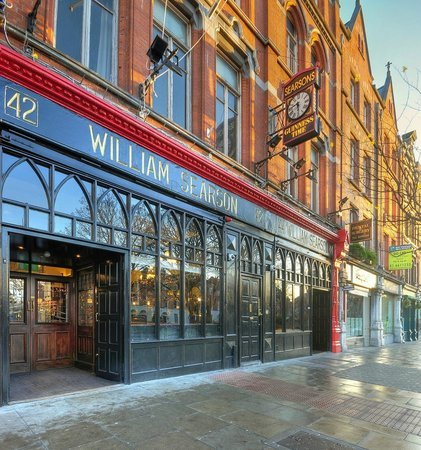

Hours later, Kavanagh was set upon in the environs of the Baggot Street Bridge. ‘Over you go, you f*****r,’ his assailant whispered as he was bundled over the wall. After one drink (in addition to those he’d previously had in Searsons) Kavanagh blacked out. However,he was able to recall the identities those present, and in particular those apparently immortal words. Kavanagh was in little doubt, it had been Dinny Dwyer who had whispered in his ear.

Whether he was pushed, or fell into the canal is unclear, though it is generally accepted that the poet descended fifteen feet into the water, and climbed another ten feet over a wall on his way out. In his own account of the event, he compares his brush with death with his survival of the “world’s most popular and deadly disease”, making reference to his “supernatural powers” he had previously discussed with “friends from London.”

The poet’s speculation as to motive is characteristically dramatic. Apparently, it all came down to “poetic jealousy.” Earlier in the year, he had uncovered what he described as a “racket” in the Irish spray painting industry, which he subsequently divulged in the Farmer’s Journal. Naturally, the “underworld” had reacted by trying to silence him. The sinister forces in question would appear to be some of Kavanagh’s good friends. It is hard to tell which would have been more controversial; to fall foul of Irish spray painters, or to be friends with Patrick Kavanagh remains unclear.

That said, Kavanagh was upbeat enough in the aftermath to write another piece in the Farmer’s Journal. “If you find yourself hated, then you will also find yourself loved” he reflected, and it was true that Kavanagh had friends on whom he could rely. Patricia Murphy was a published poet in her own right, and was soon to establish her own quarterly magazine entitled Nonplus. However, on the evening in question it was her training as a doctor which was more immediately relevant when the shivering Kavanagh arrived on her doorstep at Wilton Place off Baggot Street. Having no doubt lent Kavanagh a friendly ear, she gave him money to buy a new suit and watch the following day.

It was in his new garb that he met his assailant, supposedly catching sight of his face in a mirror in Searson’s. The sight of “Banquo’s ghost” alive and well, enjoying a pint was apparently enough to send the would-be murderer on his way. The identity of this man is an area of contention. Kavanagh does not name the man in his account, nor do his brother Peter, or Antoinette Quinn in their biographies.

Indeed, the only name attached to the incident is Dwyer’s, and though the incident has largely faded from view, there are those making a case for the defence. A letter published in the Irish Times in November 2005 laments frequent references to Dennis ‘Dinny’ Dwyer in connection with the incident. Owen Dwyer, son of the accused and writer of the letter, challenges Kavanagh’s account on several fronts, principally that his father did not bundle the poet into the canal while muttering obscenities. It is absurd to “anyone who knew (Dwyer)” that he could be described as a “skulking underworld figure”, he argues. Dwyer was out of sorts with Kavanagh, but it was not Kavanagh’s insights into the paint sector which rubbed him up the wrong way. Rather it was an unfortunate remark Kavanagh had made about Dinny’s other, mentally handicapped son.

Kavanagh concedes in his own account that “if a man is known to take the odd drink” it may undermine his version of events in circumstances such as these. He sticks to his guns however, and says it is therefore the “oldest and most popular method” for disposal of whistleblowers and purveyors of the truth. The letter writer’s father takes a different view. Kavanagh either fell in the canal relieving himself and “opportunistically” stated he had been pushed, as he had been “blackballed” by Dywer and his wife who were also benefactors of his at the time. However, there are holes in the account. In a move likely to entice literary conspiracy theorists, Quinn points to Kavanagh’s discovery of his hat and betting card on the canal bank, which suggests he entered the water from there rather than the bridge.

Another possibility is that the story was entirely fabricated in order to alleviate the guilt Kavanagh felt over the remark, which was apparently “out of character” for the usually compassionate man. Whatever the truth of the matter, Dwyer was a “responsible” and “moral” man who “chose work over the self indulgence” of the “bohemians” he supported financially.

Whether fact or fiction, the incident had a profound effect on the poet. Quinn goes so far as to suggest that Kavanagh’s near drowning as a contributing factor in his attraction to his future wife, Katherine () (apparently possessed of a ‘warm personality.’) She also suggests it was gratitude on Kavanagh’s part that led him to make a substantial contribution to the first issue of Patricia Murphy’s Nonplus, as she credits the medical attention administered by Murphy as the reason behind Kavanagh’s instantaneous recovery.

In the poem Shancoduff, Kavanagh tells the reader how he ‘scaled the matterhorn’ with ‘a sheaf of hay for the starving sheep.’ Such tongue in cheek self-mythologisation speaks to the poet’s often irreverent poetic register. Whether Kavanagh fell or was pushed, the poet clearly relished the opportunity to put his Parnassian inspiration to such mischievous use.

Featured Image Source