Benedetta Carlini, Fallen Visionary

Benedetta Carlini had the misfortune of being born into the wrong time. If she’d been born a few hundred years earlier (or even a hundred years later), she’d be Saint Benedetta of Pescia. As it was she was born in 1591 in Italy, a period when the Catholic Church was undergoing a sustained self-examination. Triggered by the Protestant Reformation, this was the “Counter-Reformation” – the church doing its best to evolve or die in response to this new existential threat. This self-examination would have dire consequences for Benedetta.

From birth, Benedetta was destined for the convent. Her family lived in the mountains a few miles from the town of Pescia, a town which owed its livelihood to an act of theft a thousand years before. In those times the only source of silk was China, and they held the secret of producing it close. Around 552AD, two monks stole silkworm eggs and mulberry bushes from China and sold them to the Eastern Roman Empire. A thousand years later, Pescia was a prosperous town surrounded by farms where mulberries were cultivated and silkworm cocoons were harvested. Benedetta’s father owned one of those farms. It was a common practice at the time for people to pledge that an unborn or newly born child would be “dedicated to the church” in order to show their devotion, with the child being put into the priesthood or into a convent as appropriate. Benedetta was one such, her future sacrificed to her parent’s piety. In the year 1600, when Benedetta was only nine years old, her father paid the required dowry [1] to the convent and handed over his daughter.

The order Benedetta was enrolled in was one of the more obscure ones – the Sisters of the Immaculate Conception of the Virgin Mary, more commonly known as the Theatines. The order had been founded in 1583 by the Venerable Ursula Benincasa, a nun of the Order of St Claire who had seen a vision of the Virgin Mary and of Saint Catherine of Sienna. The fame she gathered from this had led some to accuse her of being possessed by a devil, but she had been cleared by the church in Rome and had gained enough authority through this to found an order of her own. The venerable Ursula was still alive when Benedetta joined the order, and as she grew up in the convent she would have been taught a lot about the visions of her order’s founder. In 1617 Ursula had her most famous vision, where Jesus (or in some versions Mary) appeared to her. In the vision he praised her order and promised them salvation. Ursula asked him to extend the blessing to those outside the church, and it was agreed that those who wore a blue scapular to symbolise the order’s habit and lived a chaste and devout life would be so blessed. The blue scapular remains one of the most popular such scapulars to this day.

Ursula died in 1618, and the resulting power vacuum in the order may have been what led to Benedetta Carlini becoming the abbess of her convent shortly afterwards. She was reportedly very intelligent and a good administrator, but just under thirty was still very young for an abbess. Her standing was bolstered by the fact that, like the Venerable Ursula, Benedetta had visions. She had been having them for quite some time. At the age of 23, while praying one morning, she found herself “in a garden, surrounded by fruits and flowers”. Over time the visions increased in intensity and in detail, and Benedetta became quite well known for them. While she was in the throes of these visions she was unable to communicate or even acknowledge those around her, and the visions took such a physical toll that she was filled with pain, and had difficulty sleeping. [2] As a result, she was assigned a keeper to watch over her as she slept – Bartolomea Crivelli (known as Sister Mea), who had acted as a body servant for the previous abbess.

On the second Friday of Lent 1619, Benedetta received an unmistakable sign of divine favour – the stigmata. Prior to this she and others had fretted over whether her visions were divine or diabolical in origin, but by manifesting the wounds of Christ she proved their divinity. A vision she described which accompanied these wounds had Jesus appear and tell her that “he was God and that he wanted her to suffer for the rest of her life”. To the minds of the time such suffering was holy and to be welcomed, and so Benedetta described feeling “great contentment” at this. An even greater vision followed a few weeks later, on the second day after Easter. Jesus appeared to Benedetta to ask her to give up her heart to him. Sister Mea described how Benedatta spoke first in her own voice and then in the voice of Jesus, and how she cried out in pain as her heart was taken from her. She repeated Benedetta’s words:

…[H]ow can I live without a heart now that you have left me without one? How can I love you?

After this, Benedetta fell into a semi-catatonic state for three days, failing to react to anyone around her. On the third night she cried out:

Oh my bridegroom, did you come back to give me back my heart?

Mea then described seeing the stigmata on Benedetta’s side seem to swell, and to see the shape of the heart move under her flesh and up under her ribcage. After this Benedetta was restored to her senses.

In previous times Benedetta’s visions would have been immediately accepted as proof of sainthood, and to many among the peasantry they were just that. An unofficial cult sprang up around the convent. The church, however, was much more suspicious of such independent religious mysticism. Too many independent religious thinkers had splintered away from the church over the previous century, and so non-conformity was immediately to be regarded carefully. Still, at first glance they found little to be concerned about with Benedetta’s visions and she received an implicit seal of approval. But she was watched carefully, and only a few months later that scrutiny bore fruit.

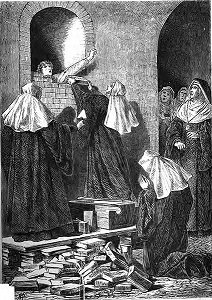

It’s difficult to know how much to credit of the stories of Benedetta’s actions in the summer of 1619. All we have to go on are the words of those who would eventually condemn her, and it’s impossible to tell how much of that was exaggerated or fabricated by them. These accounts say that Benedetta’s nocturnal visions, where she spoke with the voice of Jesus, gradually began to manifest in her waking life as well. Catherine of Sienna, the patron saint of the Theatines, also spoke through her. The most notable of those she channeled was an angel named Splenditello, who she described as a beautiful young boy in a white robe. While possessed by Splenditello her voice and mannerisms changed so notably that the nuns said it was as if she became a young man herself. These voices issued proclamations, edicts such as banning meat and cheese from the convent and praise for the virtues of those nuns who took up the old custom of self-flagellation. The capper to the stories was a ceremony where Benedetta took to the pulpit in front of the whole convent. For a woman to preach like this was a major breach of church regulations, but it was the content of her preaching that was most shocking. It took the form of a wedding ceremony between Benedetta and Jesus, as channelled through Benedetta. Through her mouth Jesus gave a long ceremony about Benedetta’s holiness and superiority, ending with an exhortation that she should be “the Empress of all the nuns”.

Though the sisters of the convent had gone along with Benedetta so far, this was a step too far even for them. In several accounts, the official investigation began the very next day. However, giving the lie to some of the stories about Benedetta’s conduct, the initial investigation actually endorsed her. The initial investigation was led by a local Provost named Stefano Cecchi, and after several months he came to the conclusion that Benedetta’s visions were indeed divinely inspired. She remained in charge of the convent. But her authority among the nuns was slipping, while her growing status as a cult figure among the peasantry made the local nobles nervous. In 1622 the investigation reopened. Though Provost Cecchi was still present, the lead investigators were two Capuchin monks from Florence who had been sent by the papal nuncio to the Duke to sort out the situation. How much they had been “encouraged” to discredit Benedetta is unknown, but the undercurrent was doubtless there. The Capuchins had a reputation for being unwavering foes of any kind of heresy, and so the choice of Brother Lorenzo Geri de Pistoia and Brother Michelangelo da Soragna sent a clear message.

Benedetta had no shortage of enemies in the convent by now. Many of the nuns resented her authoritarian rule and self aggrandisement. Her youth probably made this sting even harder. As a result the Capuchins had no shortage of grievances to mine. Some of the nuns reported to the investigators that in defiance of her own rules the abbess was having salami and cheese smuggled in to the convent. One said that a gold wedding ring, which had “miraculously” appeared on Benedetta’s hand, left marks on her other fingers that showed it was a cheap imitation (hardly the stuff of miracles). Others claimed that they had seen her prick her palms with a needle to create the stigmatic bleeding. But it was when they interviewed Sister Mea that they got the testimony they needed to unseat this worrying abbess, though it was far from what they had expected.

It is from Sister Mea’s testimony to the first investigation that we get the accounts of Benedetta’s receiving her stigmata, and of her “heart removal”. To the second set of investigators she told a far different tale of her nights with Benedetta. She told them of how Splenditello, the young boy/angel spirit who possessed her, had apparently taken a fancy to Sister Mea. During the day, while Benedetta had been channelling him, Splenditello had taught the young novice how to read and write. But at night, according to Sister Mea:

At least three times a week…Benedetta would grab her by the arm and throw her by force on the bed. Embracing her, she would put her under herself and kissing her as if she were a man, she would speak words of love to her. And she would stir so much on top of her that both of them corrupted themselves.

Sister Bartolomea’s testimony actually put the Capuchins in somewhat of a legal conundrum. She herself had accepted Splenditello’s assurance that their actions were not a sin, as they had been driven by divine intention. The monks on the other hand were pretty sure that this was the wedge they needed to dislodge Benedetta. But the legal status of non-penetrative lesbianism in 17th century Italy was unclear. They tried to find out from Bartolomea if “material instruments” had been involved – if the relationship had involved some form of penetration then the statutes against sodomy could have been deployed against them. But though the novice’s testimony makes it clear that Benedetta had compelled her to perform oral sex acts, this type of non-penetrative sexual activity was not something the (entirely male) people who had drawn up the laws had considered. In the end the two classed it simply as “fornication”.

In the normal course of events, this would have carried a relatively light penalty – two years of penance, plus the loss of Benedetta’s status as abbess. But this was not the normal course of events. The fact that Benedetta admitted that it was “Splenditello” who had committed these acts allowed the monks by inference to class all of Benedetta’s visions as diabolic in nature, and as such to condemn her. However by that logic she was not a heretic – simply one who through weakness had allowed the devil to corrupt her. Benedetta confessed to these sins, and so she was spared death. Instead, the vindictive nuns devised a more cruel punishment – a living death. Some of the sisters of the Theatine Order practised hermitage, where they would spend months or years in solitary cells serving penance. Benedetta was condemned to involuntary hermitage, for the rest of her life. She spent 35 years trapped in solitary confinement, deprived of all human company [3] until she finally died in 1661. [4]

Benedetta was not forgotten by the common people who had considered her a saint when she was imprisoned, and since the churchmen had suppressed the scandalous nature of her relationship with Bartolomea the rumours spread that her confinement had actually been a voluntary self-isolation from the world. When she died she was given a burial that fitted this status with the public, and there was some movement to even have her beatified as a saint. This was blocked by those who knew the truth, though no explanation was ever given. In time Mother Benedetta Carlini became a historical curiosity, a symbol of the fall of the mystical saints. She was expunged from the official histories of the Theatines, and was eventually forgotten. It was the American historian Judith Brown who rediscovered her in the 1980s.

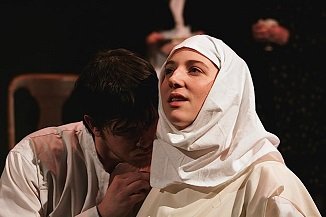

Judith had already written one book about the Renaissance history of Pescia, and while researching for another she discovered the records of Benedetta’s trial in the state archives of Florence. She first wrote an article about the discovery, and then made Benedetta the subject of her second book, Immodest Acts: The Life of a Lesbian Nun in Renaissance Italy. It was a fairly dry and scholarly work, and didn’t really live up to its lurid title. But a lively review in the New York Times and a subsequent rebuttal by rival historian Stephen Greenblatt (which basically boiled down to “lesbianism hadn’t been invented in the 17th century”) [5] helped both the book’s sales and Benedetta Carlini’s profile enormously. At the time homosexuality was still illegal in many Catholic countries, including Ireland, [6] and so the narrative of a a young woman martyred for her sexuality (while not entirely accurate) had a great deal of resonance. Benedetta became a symbol, not just of historical persecution of lesbians but proof that (Professor Greenblatt’s assertions aside) lesbianism had existed in history outside of Sapphic verse. To this day she remains an important symbolic figure, with not one but two plays made about her life in the last few years – Stigmata by Carolyn Gage, and Vile Affections by Vanda. It’s clear that, despite the attempts of the establishment of her time to brush her under the carpet, we’re not going to forget Mother Benedetta Carlini any time soon.

Images via wikimedia except where stated.

[1] A requirement ostensibly as she was becoming a “bride of Christ”. As it was usually a lot less than a real dowry, a lot of respectable middle-class families saw it as a cheaper alternative.

[2] The more cynical among you may be muttering about temporal lobe epilepsy and the like. Of course at this distance it is impossible for us to draw any real conclusions. Benedetta at least seems to have been convinced of her sanctity.

[3] And denied any help with whatever it was that had caused her fits and constant pains for the last ten years.

[4] For her confession Bartolomea was spared any punishment. She died in 1660, a year before Benedetta.

[5] Yes, I’m being unfair and reductionist – Professor Greenblatt’s point is more that sexual attitudes at the time were different and to judge them by modern standards is incorrect. On the other hand he makes this point in an extremely mansplainy way, so I feel I’m justified.

[6] Though those laws, ironically, only applied to penetrative activity.